This is the first of a series of articles on the 2012 San Francisco International Film Festival, held April 19-May 3.

The recently concluded 55th San Francisco International Film Festival screened nearly 200 films (including shorts) from several dozen countries.

Awards were handed out to British actor-director Kenneth Branagh and actor Terence Stamp, French cinephile Pierre Rissient, who chose Fritz Lang’s House by the River (1950)—a highlight of the festival—to follow his award ceremony, and Barbara Kopple, best known for her Academy Award-winning documentary about a coal miners’ struggle, Harlan County USA (1976).

Another high point was the presentation of a restored version of Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949), based on a screenplay by Graham Greene, in honor of the late Bingham Ray, former executive director of the festival. Ray was hired to replace Graham Leggat who had held the position for five years before he died last August of cancer.

Tens of thousands attended the event, originally founded in 1957 and which advertises itself as the “longest-running film festival in the Americas.”

Naturally—despite all the work expended on them—the films at this year’s San Francisco festival cannot be uncritically accepted as the final word in moviemaking. For a film to have enduring value, something true, important and beautiful, something hitherto hidden from view or passed over must be brought to light in it through images, situations and dialogue. Moreover, substantial art always bears a significant relation to human life and social development, to the specific moment of its creation.

Along these lines, what is happening in the “life” of great masses of humanity today?

Last year will go down in history as one that saw the resurgence of open class struggle on an international scale. Mass protests toppled the dictatorship in Tunisia, followed quickly by social upheavals in Egypt ousting despot Hosni Mubarak. Weeks later, major protests began in Wisconsin against attacks on workers’ rights. In Europe, mass demonstrations against austerity dictates swept Spain and Greece. By year’s end, the Occupy Wall Street movement announced itself as the first significant popular movement against social inequality in the US in more than a generation. Occupy protestors were routinely beaten, jailed and charged with crimes all over the country-—and not far from the venues showing this year’s crop of films in San Francisco.

So, to what extent was all, or any of this, reflected in the films shown this year? Which artists were able to capture something of these historic movements in concrete stories of individuals, households and neighborhoods? Where in daily life did they glimpse this massive human potential, the suffering and desire for change? Which directors are carefully studying the world around them?

A healthy, new movement in film has not yet arrived, but there are green shoots. Social reality—in spite of much accumulated confusion—is registering itself in a number of films, some of which I was able to view, such as Ra’anan Alexandrowicz’s The Law in These Parts (Israel), Anca Damian’s Crulic: The Path to Beyond (Romania) and Mathieu Kassovitz’s Rebellion (France). There were, as well, a number of works from better periods in the history of film that merit reconsideration, including Lang’s The House by The River and Reed’s The Third Man.

There were also a few very poor films that require comment, such as Michael Winterbottom’s Trishna and Francis Ford Coppola’s Twixt. Unfortunately, there were other potentially interesting efforts I was not able to review such as Kim Joong-hyun’s Choked, Craig Zobel’s Compliance, Johnnie To’s Life Without Principle and Cai Shangjun’s People Mountain, People Sea.

The Law in These Parts

The Law in These PartsAlexandrowicz’s The Law in These Parts is an extraordinarily penetrating documentary dealing with the Israeli military legal system in the Occupied Territories on the West Bank and in the Gaza Strip over the last 45 years. The film is told in five chapters roughly corresponding to a few foundational legal opinions.

The filmmaker, although a self-acknowledged legal outsider, conducts a series of interviews with the professionals charged with setting up and carrying out the occupation regime from 1967 to present. The film was far and away one of the best and most important shown at the San Francisco festival this year.

Ra’anan Alexandrowicz

Ra’anan AlexandrowiczAlexandrowicz was born in Jerusalem in 1969 and has grown up with the occupation. After studying film in Jerusalem, he focused mainly on documentary work, culminating in the making of The Inner Tour in 2001—a film that follows a group of Palestinians on a three-day bus tour through Israel. This was followed by his first fiction feature James’ Journey to Jerusalem (2003).

The Law in These Parts begins with a quote from military judge Meir Shamgar to the effect that the rule of law isn’t just a set of norms, but, more importantly, norms that win the confidence and respect of every individual. Almost at once, it becomes clear that the Israeli legal project in the Occupied Territories is, by this measure, a horrible failure.

The filmmaker’s interviewing technique develops from a tone of respect, occasional admissions of ignorance and almost child-like curiosity into a subtle, but highly effective form of cross examination of Israeli officials. What emerges, although largely hidden from public scrutiny as the filmmaker reminds us, is something already understood by every Palestinian.

Behind all the professional scholarship, official adherence to legal forms and procedures and the use of impenetrable professional jargon, lies a brutal military regime utilizing torture, forced confessions and systematic theft to strip the occupied population in Palestine of virtually all democratic rights and human dignity, or as one former military judge, Dov Shefi puts it: “What the IDF [the Israel Defense Forces] says, goes.”

Alexandrowicz’s sober, dispassionate tone is one of the film’s great strengths. Instead of simply offering a denunciation of the perverted justice system that reigns over the Palestinian population, we are shown instead its birth, development and breakdown over decades, as a logical process stemming from the needs of a conquering military power to permanently subjugate a population in its own land.

The Law in These Parts

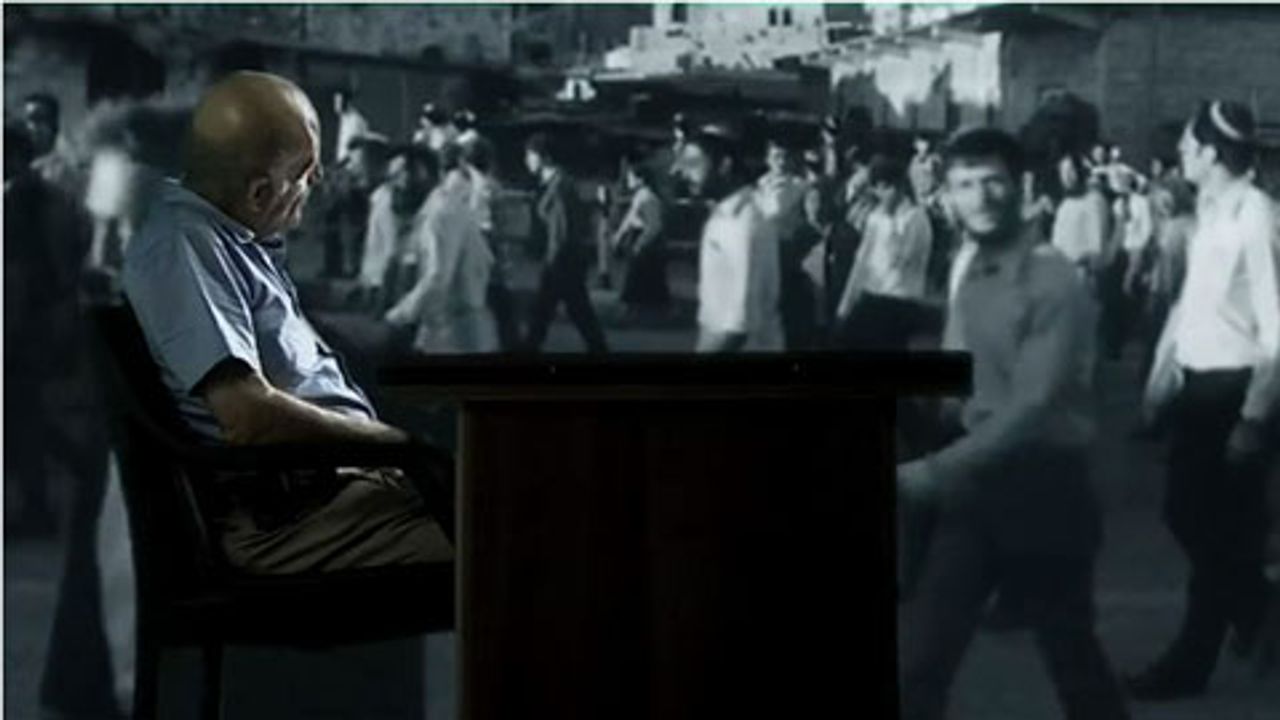

The Law in These PartsThe film’s approach is unusual and compelling. At the outset the viewer watches the silhouettes of a film crew moving about behind the scenes constructing a rudimentary office in front of a large, wall-sized movie screen, as Alexandrowicz speaks off-camera on the film’s subject matter, the nature of documentaries and his personal goals for the endeavor. Film images of the Occupied Territories from 1967 to the present are projected on the big screen during the interviews.

The military lawyers and others are questioned at the desk in front of the screen. Although they do not comment on the images, they gaze at them during the interviews and occasionally point to the screen. The images are not of the most disturbing variety, they are not meant to shock or upset those questioned, but rather they seem designed to enhance the memories and emotions of the subjects.

The filmmaker explains that the backdrop footage is compiled from other documentaries of the occupation made by various Israeli filmmakers. The images are nonetheless quite potent at times, especially their propagandistic elements, such as one clip taken shortly after an Israeli military victory documenting a visit by war hero Moshe Dayan to a beach crowded with Palestinians in the Occupied Territories accompanied by the blaring horns of a triumphant military march.

Alexandrowicz is aware of the significance of his film and proceeds throughout with great care. He makes a point of reminding the viewer that he doesn’t provide time for the more prominently portrayed victims of the occupation to tell their side of the story. Later in the film, when an Israeli military judge confesses that he never questioned military intelligence, followed its recommendations lockstep in every case and even knew defendants were being tortured before their court appearances, Alexandrowicz cuts the audio and tells the viewer that he has decided not to show us the rest of the interview.

Beyond simple caution, he seems to want us to witness his own internal conflict. The filmmaker has been open about the at times painful exchange between the documentarian and his subject matter—a process that seems in part to have prompted the creation of The Law in These Parts: “In mid 2004, I got a phone call from a boy who had just turned 16 who was in The Inner Tour. He was taken from his home in the middle of the night by masked Israeli soldiers and charged with throwing stones at a military Jeep and was held in a maximum security prison … For the first time in my life I found myself in an Israeli military court room, witnessing the mechanism with which my society purports to administer justice to Palestinian residents of the territories we have occupied since 1967. This event profoundly changed my understanding of the situation in which I live.”

Perhaps the most valuable portion of the film is “Chapter 2: Terrorists and Criminals.” “Today the distinction between soldier and terrorist is deeply rooted in our legal and political discourse. But at the end of the 1960s it was necessary to cement this distinction in the law,” Alexandrowicz explains, before introducing the 1969 case of the IDF v Omar Mohammad Al-Qassem and eight others in Ramallah, all members of Fatah.

The defendant, Qassem, tells the court he is certain this is his land, but he left when the occupation began and returned with other fighters to liberate Palestine. Although the evidence showed that Qassem had only engaged soldiers in battle—and he asserts he was merely a soldier fighting soldiers—the court found that Qassem and his organization were terrorists with no legal protections under the international laws of war, specifically the Geneva Convention.

In his ruling Judge Abulafia concedes the Geneva Convention grants special status to lawful combatants and that even includes members of liberation organizations, but holds that this status must first be earned by following the rules of war in battle. Abulafia finds that the entire Palestinian liberation movement does not follow the rules of war, citing civilian victims unrelated to the particular facts of Qassem’s case, and declares him the member of a terrorist organization, specifying that Palestinian liberation fighters like Qassem will never have any rights under international law.

The Law in These Parts is a great success not merely because of the intelligence and sensitivity of the filmmaker, his access to high military and government figures, although all that helps a great deal, but primarily because Alexandrowicz is earnest in his desire to make sense of his subject matter. He is not hustling to make a name for himself, to get a Hollywood contract, a book deal or a spot as a pundit on CNN. He is principled artist, a man seeking to understand a tragic reality and to prevent its recreation on a global scale.

The Law in These Parts will be screened at the upcoming Seattle International Film Festival on May 27 and May 29.

To be continued