A World Socialist Web Site reporting team recently visited the eastern Ampara district of Sri Lanka and spoke to survivors of the tsunami that devastated much of the coastal belt on December 26. According to local officials, about 25,000 people were killed and another 166,000 were left homeless in the district. Six months later, more than 40,000 victims are still living in inadequate accommodation with little or no government financial assistance.

Almost all emergency refugee camps have now been closed—only five remain housing 3,450 people. Most of the tsunami victims—37,321—have been moved to 100 temporary shelters. But the change of name and location has not resulted in any significant improvement in living conditions. Many of the refugees are caught in a bind. The government has arbitrarily banned rebuilding of homes within 200 metres of the sea—where they used to live. At the same time, official relocation and reconstruction programs have not even begun.

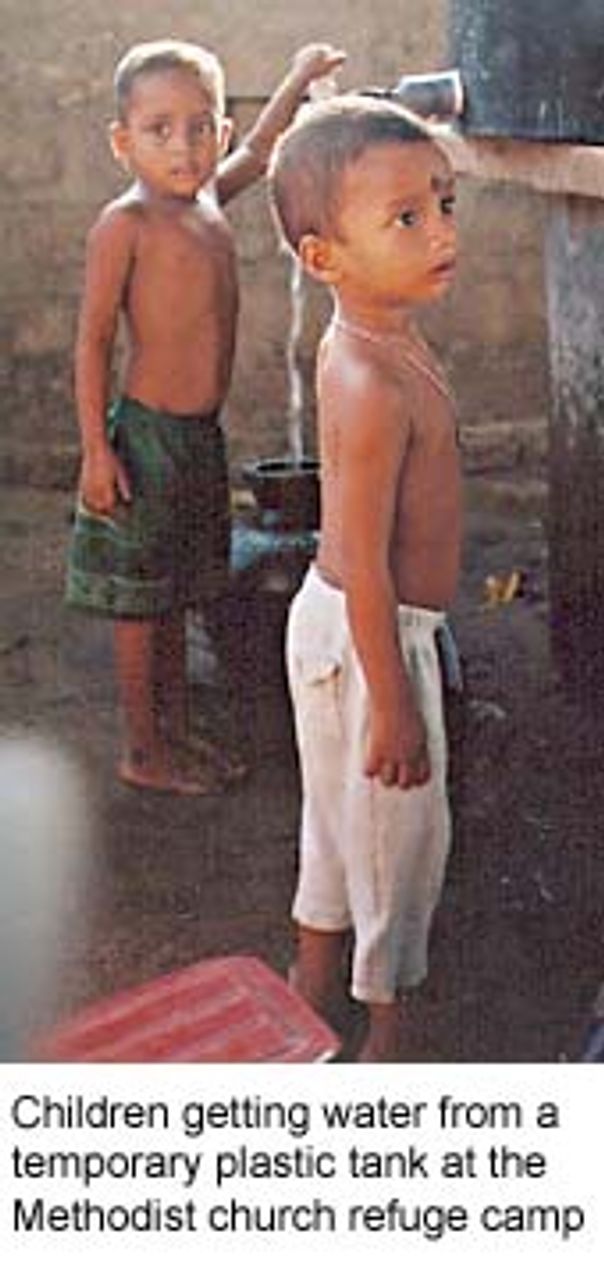

At the YMCA and Methodist church at Akkaraipattu, all the refugees were fishermen and their families from the village of Sinna Muhathuwaram. The main hall of the YMCA has been partitioned into tiny rooms—less than three by three metres—using cellophane cloth. Outside there are a few canvas tents. All of the facilities are primitive—water, for instance, comes from a temporary plastic tank. Yet 37 families live in the camp.

At the YMCA and Methodist church at Akkaraipattu, all the refugees were fishermen and their families from the village of Sinna Muhathuwaram. The main hall of the YMCA has been partitioned into tiny rooms—less than three by three metres—using cellophane cloth. Outside there are a few canvas tents. All of the facilities are primitive—water, for instance, comes from a temporary plastic tank. Yet 37 families live in the camp.

A similar situation exists at the Methodist church. Families live in small huts constructed from wooden planks and tin sheets. While the rooms are somewhat larger—three by five metres—the facilities are still limited. The buildings are unbearably hot during the current dry season. There is just one water tank for 74 families. While the water from the local well stinks, people say they have no alternative but to use it for washing and bathing.

Most of the fishermen have not been able to return to their occupation. The accommodation is not near the sea and their boats are not suitable for fishing in the nearby lagoon. A few have nets, but most are forced to try to make some money as poorly paid day labourers.

A. Thavanathan, a middle-aged fisherman, explained: “We can’t go fishing from here. The sea is situated far away. How can we transport boats from here everyday. Even if we take the boats by vehicle what do we do after fishing? Previously we used to live by the sea. So we were able to repair any damage and look after the boats. Now nobody lives by the shore. Who can look after our boats when we are not there?”

His wife Pramawathi, who lost two of her four children during the tsunami, said: “This is like living in a hell. Living in our own place with one meal [a day] would be better than this. If the government gave us a piece of land in a suitable place, at least we could build a hut and live there.”

R. Vijayarajah said there were about 65 fishermen at the YMCA camp, but only 10 had been given boats. “We were given beach nets. You can’t go fishing in the deep sea with these.” Chandramalar, a widow, said she used to be a fish vendor at the local market, but had lost everything. Without money, she cannot start her business again and has no idea what she will do in the future.

Thanabalasingham, a young mason, said: “The officials say we have to shift to Kawdapetti but we don’t like the idea. It is seven kilometres from Akkaraipattu town. There are no hospitals, schools or water facilities. It is just forest. The divisional secretary told us to go there but we refused.”

Referring to killings in the district, he added: “We don’t want war. All Sinhalese, Tamils and Muslims must unite together. We have suffered because of the war. Before the [present] cease-fire, we couldn’t travel by bus. We had to get out and show our identity cards all the time. Sometimes people were arrested. Sometimes they were killed. In just this camp, there are 15 widows who have lost their husbands because of the war.”

Pushapanandani, a female student at the Ramakrishna collage, complained: “I am sitting for the university entrance exam next year. But there is no place to study—no table or any other furniture and it is also noisy. Even after finishing their studies, many young people have no job. Some work as volunteer teachers. They are employed by various NGOs [non-government organisations] and get only a small allowance.”

Rasaiya Thangarani commented: “We were promised a monthly allowance of 5,000 rupees ($US50) but only got it for two months. We need 500 rupees a day just for meals. My husband suffers from asthma. Every week we spend 200 rupees on medicine. The rice they distribute at the camp is not good. You can’t eat it. From government food stamps, we each get 200 rupees in cash a week and dry rations worth 175 rupees, mainly rice, lentils and sugar. Some weeks we don’t get even that.”

“I lost one child in the tsunami and I have a son and a daughter going to school. One is in grade six and the other is in grade seven. They don’t have bicycles and have to walk long distances. Today my daughter quarrelled with me about walking and refused go to school.”

At Bathur Nagar, there were 18 families living in temporary huts. N.T. Faseela told us that the conditions at their camp were not much different from others. She said that children were getting fevers and stomach illnesses because of bad drinking water. “Because of this life of hell we are thinking about going back to where we lived before. Even though it is near the sea we don’t care. If sea takes us away, it is better than living in these terrible conditions.”

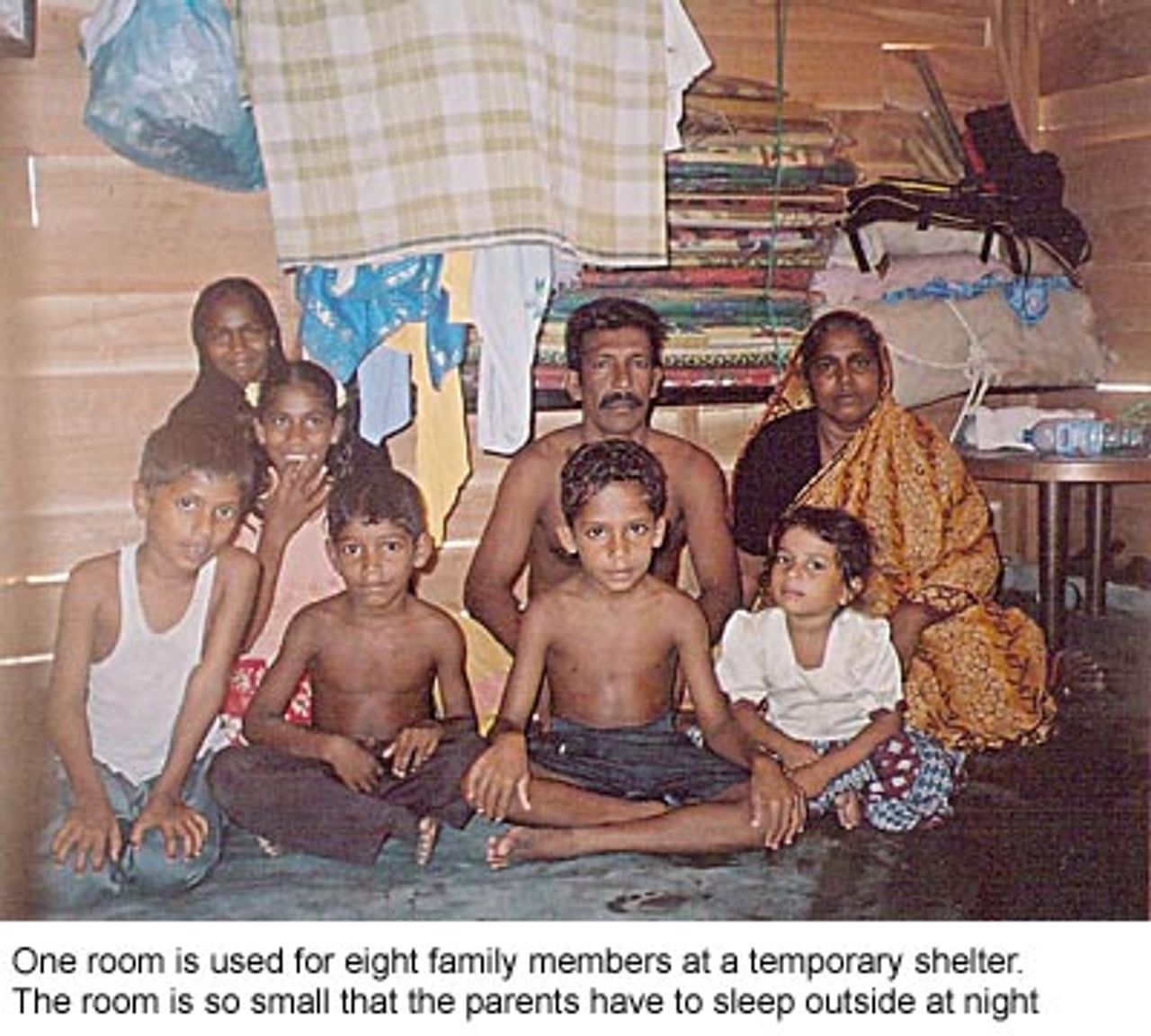

Another 38 families were living at the Mira Nagar B temporary settlement. Jamaldeen Najeema explained: “My husband used to work using in his own three wheeler [cab]. But we lost it in the tsunami. Now we don’t have any income. Because of the hot weather, we look for shade outside the camp during the day and only come back for meals and to sleep. At night, the children sleep inside. My husband and I sleep outside in the open air because of the lack of room. If it rains it is real problem.”

Life in the buffer zone

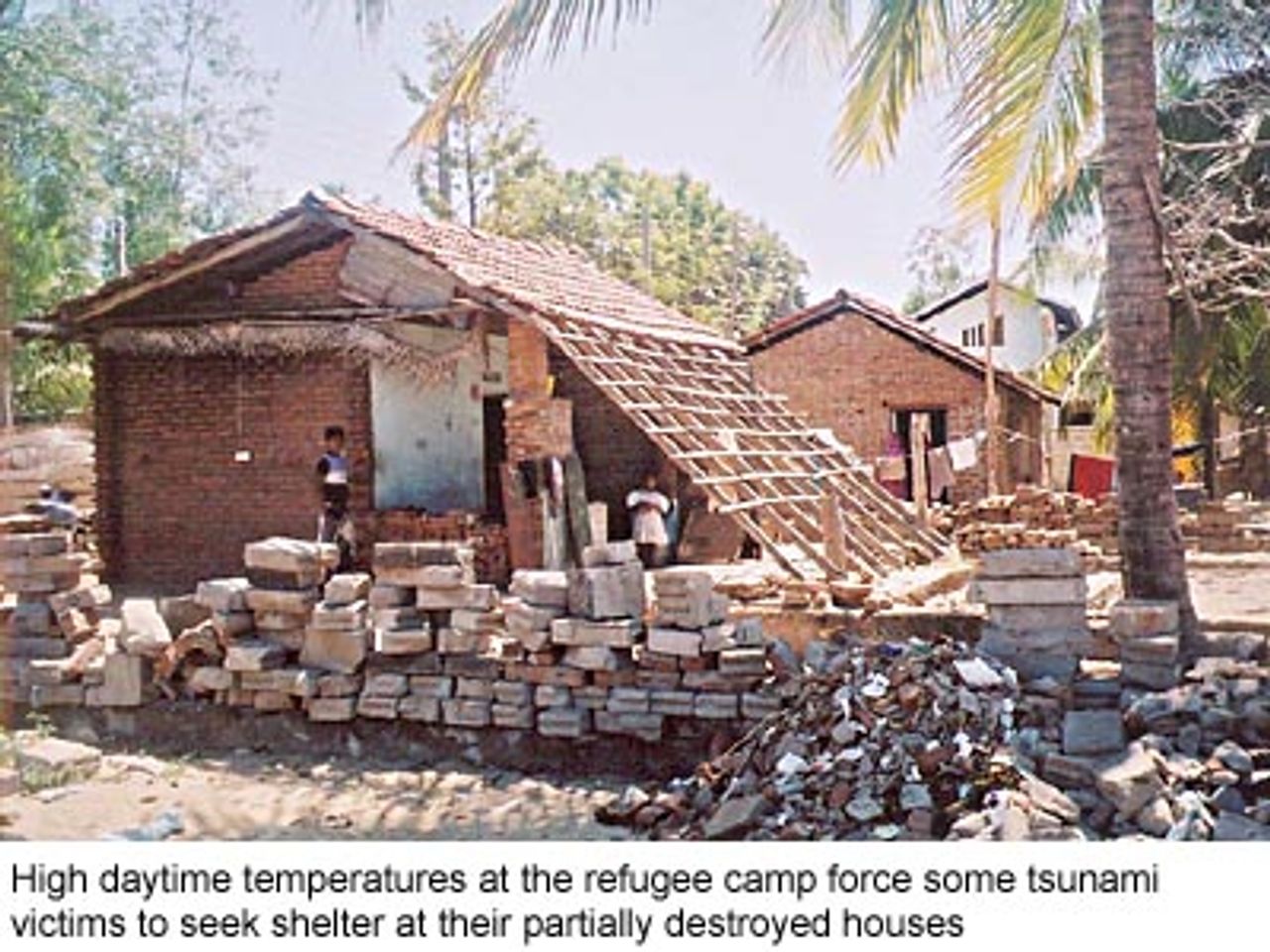

Because of the living conditions in refugee camps, some tsunami victims have returned to their damaged homes, even though they are within the government’s 200-metre buffer zone.

Mohammed Ismail, a fisherman, is living just 75 metres from the sea. “Two days after the tsunami I returned to my house,” he said. “I don’t know any other job so decided to come back. My adult daughter used to live with us but she is afraid to return. I don’t have a boat or nets. So I prepare nets for others. To get one net ready takes four days and I am paid 1,000 rupees. The government refuses to give us money to repair this house.”

M.P. Fathima and her family were living in terrible conditions in a badly damaged house. Her husband suffered psychiatric problems as a result of the tsunami and is unable to work. Two of her three children are of school age but she has no money to send them to school.

Abdul Carder, a fisherman, explained: “My village, Meera Nagar was destroyed by the tsunami. We have also been affected by the war between the LTTE [Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam] and government forces. In 1985, the LTTE told us to leave our houses at Puttampai. So 150 Muslim families came here. Now the government is telling us to go to Nooraisolai. Most people here are fishermen and day labourers. What can they do there [at Nooraisolai]?

“Politicians don’t help us. Our minister Abdullah was in Japan when the tsunami struck. One week later he came and promised to do everything to help us rebuild our lives. But we haven’t seen him since then. He went to Mecca. Is it necessary to visit Mecca when people are suffering?” Carder and his family did not get a place in a temporary shelter, so they are living in what remains of their home.

Nasira Maguroop commented: “People who used to live in the buffer zone are suffering a lot. We don’t have a place to live. Not a single house has been built for us. Neither the government nor politicians want to help us. If we have an election, they will come and visit us—lane by lane. We are so disgusted that at the next election we are not going to vote for anybody.”

At the Bathur Nagar fishermen’s co-operative, its president M.L. Ahamad Mohaideen told us that all 121 members were affected by the tsunami. Their boats and nets were all destroyed. “I wrote to all the government officials but didn’t even get a reply,” he said. “So far, the government hasn’t done anything for us. Our Muslim politicians haven’t done anything for us either. Only through the NGOs did some fishermen get nets and boats.”

Mohaideen opposed the protests organised by various Muslim parties and organisations to demand a larger role in the joint aid body to be established by the government and the LTTE. “Politicians organised the hartal [strike and business shutdown] to defend their interests but not those of the people.” He also criticised the government for talking about “democracy and equality” and doing nothing. “We have to fight to get anything done. People must get things on an equal basis without discrimination on racial, religion or language.”

Commenting on the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna’s (JVP) agitation against the joint aid mechanism, Mohaideen said: “I think 70 percent of the Sinhalese people oppose JVP’s chauvinist campaign. The JVP joined the government and got the agriculture ministry and the fisheries ministry. They thought that through their ministries they could get the support of peasants and fishermen and form their own government after the next election. But they didn’t solve any problems. So now after leaving the government, they are stirring up chauvinism to divert attention from their own failure.”

Another co-operative society member, M.L. Haroon, said he had written letters to President Chandrika Kumaratunga, opposition leader Ranil Wickremesinghe, Muslim political leaders and the Ampara district secretary about the problems facing fishermen—damaged homes and the loss of personal belonging. But he did not even get an acknowledgement.

Haroon accused authorities of doing nothing concrete to help those living in the buffer zone. When he asked the village committee to look into the problems of tsunami victims, he was told to leave. “Now they don’t invite me to meetings,” he said.

The plight of youth

At Karaitivu, a group of young people has organised a temporary social club—the Kalai Mahal community centre. It has one room and a small open hall, just over 200 metres from the sea. The roof is made out of coconut leaves and the floor is just sand. They have a volleyball court covered with damaged nets, a few board games, two tables and a few chairs. The daily newspapers are also available. Before the tsunami, the regional council used to pay the subscription for one newspaper. Now it refuses to pay for anything on the excuse that the centre has no permanent hall. The old one was destroyed.

S. Sivakanth, a supervisor, commented: “After the tsunami we were all feeling low. Now nobody wants to return here to live. All the water wells in the area are salty. People have to pay 2,500 rupees to get a connection to the water main. Those who can’t afford to pay have no water.”

Al Bahirathan, 22, said that even though he has done a civil engineering course at a technical college, he now worked as a labourer. “Employment is a big problem in the area. The only jobs we can find here are with NGOs. If these organisations leave the country, there won’t be any jobs. We will be out on the streets.”

M. Vinayagamoorthy said: “I passed my A levels but didn’t get a university place. I was studying for an external commerce degree when the tragedy hit us. Now I have to stop studying because all my books and notes were destroyed. I lost both my parents, my only sister and her husband because of the tsunami. Now I am living alone and working as a temporary labourer. I have had interviews with many NGOs but couldn’t get a job. After this work of clearing up is finished, I will be unemployed. Sometimes I think it would have been better if I had been killed as well.”