The following is the text of a report given by David North, national chairman of the Socialist Equality Party, to the WSWS/SEP/ISSE regional conferences, “The world economic crisis, the failure of capitalism, and the case for socialism.” This report is also available for download in PDF.

Nearly eight months have passed since the collapse of the Wall Street investment bank Lehman Brothers began the greatest economic and financial crisis since the breakdown of 1929. A growing number of economic analysts believe that the present crisis may eclipse that of the Great Depression. This crisis will be protracted—lasting years, not months—and its long-term consequences will be far-reaching. History is being made, and the world that emerges from this crisis will be very different from that which existed prior to the Lehman Brothers collapse of September 15, 2008.

The scale of the economic breakdown is difficult to comprehend. No previous event in economic history has involved the sums of money, in the trillions of dollars, that have been squandered by the governments of the United States and Europe to prop up the banks and financial institutions whose reckless activities triggered the global meltdown. If a criminal mastermind had managed to steal all the gold in Fort Knox, the value of his heist would have been far less than the sum of money turned over to the banks under the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) scheme.

The losses of the banks, according to the International Monetary Fund, are in the area of $4 trillion. Total losses approach $50 trillion, including the $25 trillion to $30 trillion decline in share values on global equity markets.

The rapidity of the global economic downturn is without precedent. Comparing the immediate aftermath of the Crash of 2008 to that of 1929, two well-known economists, Barry Eichengreen and Kevin O’Rourke, state that the present situation is worse. Production is down 12 percent, as compared to 5 percent in the six months that followed the 1929 Crash. Trade has fallen 16 percent, as compared to 5 percent in the earlier crisis. And though the signal event of the 1929 Crisis was the dramatic fall on Wall Street, the market collapse was far steeper in the final months of 2008 and the opening months of 2009.

The collapse of global manufacturing is without precedent since the end of World War II. As of March, European manufacturing has fallen 12 percent from a year ago; Brazilian manufacturing is down 15 percent; Taiwan manufacturing has dropped 43 percent; and in the United States the drop, so far, is 11 percent. As for trade, German exports are down 20 percent; Japan’s exports have fallen 46 percent; and US exports are down 23 percent.

The clearest statistical indication of the scale of the economic crisis and its shattering social impact are provided by the figures related to unemployment. The International Labor Organization’s 2009 Global Trends report makes for chilling reading. In 2008 unemployment increased by 10.7 million over the previous year, the largest increase since the Asian financial crisis of 1998. The total number of global unemployed reached 190 million, of whom 109 million were men and 81 million were women. The number of unemployed youth reached 76 million.

The ILO projections for unemployment in 2009 are based on three different crisis scenarios. The scenario that the ILO itself believes to be the most probable estimates that the number of unemployed will increase between 30 and 50 million people. The actual figure will likely approach the higher number.

The ILO states that the threshold for poverty in less developed countries is an income of $2 per day. For extreme poverty it is $1.25 per day. The organization projects that a severe economic crisis will create an additional 200 million workers living in extreme poverty. Another significant category tracked by the ILO is that of the vulnerably employed—that is, workers who endure extremely low wages, abusive conditions and negligible opportunities. The number of such workers rose, according to the ILO, by 84 million in 2008, to a total of 1.6 billion people.

While the social situation in the less developed regions is already catastrophic, the economic crisis is having a devastating impact on the working class in the advanced capitalist countries. In the 30 richest countries, the economic crisis will increase unemployment by 25 million people.

The situation in the United States continues to deteriorate. Another 563,000 people lost their jobs in April, and the national unemployment rate rose to 8.9 percent. The total number of workers unemployed is now 13.7 million, the highest in the post-World War II era. Since the onset of the economic crisis, 6,000,000 workers have been thrown out of work. In March, unemployment increased by 62,000 in California, 51,000 in Florida, 47,000 in Texas, 41,000 in North Carolina, 39,000 in Illinois, and 37,000 in Ohio. The highest regional unemployment rate is in the West, where it now stands at 9.8 percent. It is 9.0 percent in the Midwest.

On a statewide basis, Michigan’s unemployment rate (as of March) of 12.6 percent is the highest in the country, followed by Oregon with 12.1 percent of workers without jobs, South Carolina with 11.4 percent, California with 11.2 percent, North Carolina with 10.8 percent, Rhode Island with 10.5 percent, Nevada with 10.4 percent, and Indiana with 10 percent.

These levels of unemployment translate into other indices of extreme social distress: a tidal wave of foreclosures and personal bankruptcies, declining college enrollments, rising crime rates, and a general deterioration in the health and well being of the population. Wage cuts of 10 percent and higher have been imposed on workers throughout the country, eroding living standards and pushing millions of workers to the very brink of financial disaster.

What is the prognosis for the future? At what point will the “bottom” be reached and a “rebound” begin? The recent rise in global markets from their March lows is being proclaimed as the beginning of a turnaround. Aside from the direct impact of multi-billion-dollar infusions of public money into the banking system, there is little hard data that justifies various optimistic forecasts of an imminent end of the recession. Let us keep in mind that the most recent US employment statistics showed nothing more promising than a slightly less severe rate of job losses. That is not exactly great news. Moreover, speculation about an imminent “rebound” reflects an incorrect understanding of the present crisis. Of course, it is not entirely beyond the realm of possibility that there may be, at some point, an improvement in the conjuncture. Nor is it difficult to imagine that the economic situation may continue to deteriorate.

However, whatever the short-term fluctuations in the markets and other indices of the global economy, there will not be a return to the status quo ante. The previous conditions are gone and will not return. This is not only because massive damage has been done to the global financial system. This crisis marks the breakdown in the global structure of world capitalism as it emerged from the Second World War. It is not an accident that the present crisis originated in the United States. The essential significance of this crisis lies precisely in the fact that it arises out of the long-developing deterioration of the dominant global economic position of the United States.

This crisis is the form in which a fundamental restructuring of the American and global economy, and the social and class relations upon which it is based, is taking place. It can be resolved only in one of two ways: Either on a capitalist or on a socialist basis. The first, the capitalist solution, will mean a drastic lowering of the living standards of the working class in the United States, Europe and throughout the world. This solution will require massive internal repression, the destruction of the democratic rights of the working class, and the unleashing of military violence on a scale not seen since World War II.

The only alternative to this catastrophic scenario is the socialist solution, which requires the taking of political power by the American and international working class, the establishment of popular democratic control of industrial, financial and natural resources, and the development of a scientifically-planned global economy that is dedicated to the satisfaction of the needs of society as a whole, rather than the destructive pursuit of profit and personal wealth.

The crisis has laid bare the corrupt and parasitical character of the world capitalist system, based on American-inspired “free-market” capitalism that has evolved over the past 30 years. The vast enrichment of a small section of society and the unprecedented growth of social inequality were, as has now become clear, the symptoms of a corrupt and diseased economic system. In the harsh light of this crisis, an increasing number of economic commentators are acknowledging that the policies and practices that led to the present crisis can be traced back to the coming to power of Margaret Thatcher in Britain in 1979 and the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. Their dual victories led to a repudiation of the managed capitalism advocated by John Maynard Keynes and the introduction of the free-market “fundamentalism” of Milton Friedman.

There is an element of truth in this analysis, but it evades the more basic question: why did this change take place? The shift from Keynesianism to Friedmanite free-market fundamentalism was a response by powerful sections of the ruling class in Britain and the United States to an already far-advanced crisis of the capitalist system. As far back as 1967, there were growing indications that the mechanisms devised by Keynes to stabilize and rebuild capitalism in the aftermath of World War II were breaking down. The system of dollar-gold convertibility adopted at the Bretton Woods Conference of 1944, which established the stable international monetary system that provided the basis for the post-war economic expansion, was increasingly unviable by the late 1960s. In August 1971, the system broke down completely when President Richard Nixon ended dollar-gold convertibility.

Three interrelated factors contributed to the breakdown of Bretton Woods. The first was the gradual erosion in the course of the 1950s and 1960s of the dominant economic position that the United States had enjoyed in the aftermath of the Second World War. The second was a general decline in the rate of profit in the mid-1960s that placed considerable pressure on American, European and Japanese corporations and intensified global competitive pressures. Finally, the militancy of the working class, throughout the world, frustrated efforts by the capitalist class to find a way out of the crisis through the intensified exploitation of the working class.

The period between 1967 and 1975 was characterized by an international eruption of working class militancy and political radicalization. The French General Strike of May-June 1968, the massive strike wave in Italy in 1969, the upsurge of the working class in South America, the powerful strikes in Britain, spearheaded by the coal miners, that eventually forced the right-wing conservative government out of office, the strikes of shipyard workers in Gdansk that staggered the Stalinist regime in Poland, and the resistance of Greek, Portuguese and Spanish workers that ultimately shattered the dictatorships in their countries were among the most significant manifestations of a global wave of labor militancy that was assuming revolutionary dimensions. This movement extended well beyond the major capitalist centers. Throughout Africa, the Middle East, Latin America and Asia, the popular masses were engaged in mass struggles aimed at the eradication of the remaining vestiges of American and European colonialism. The struggle of the Vietnamese masses was the most heroic manifestation of this worldwide movement.

The working class in the United States played a significant role in this global process. The historic struggle for civil rights that shook American society in the 1950s and 1960s was, in essence, a struggle by the most exploited and impoverished sections of the American working class against oppression and discrimination that was rooted, in the final analysis, in the class structure of American society. In cities such as Los Angeles, Newark, and Detroit, these struggles assumed an insurrectionary form. The state governments responded by mobilizing their national guards and imposing martial law. In the case of Detroit, President Lyndon Johnson dispatched federal troops to suppress the popular revolt.

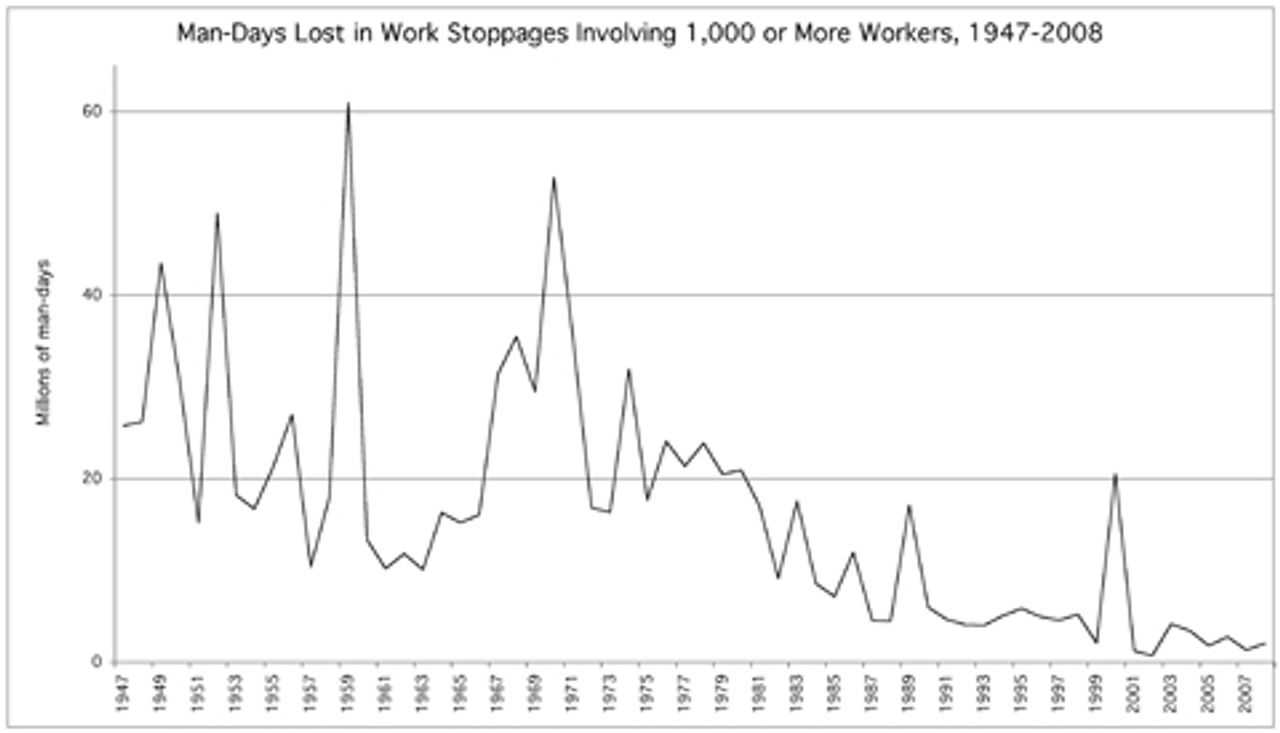

Strike activity—the most basic indicator of class militancy—increased dramatically from the mid-1960s on, among broad sections of the industrial working class. After the stormy struggles of the 1930s and late 1940s, there had been a gradual decline in strikes in the 1950s and early 1960s. An exception was 1959, when a bitter 116-day strike involving hundreds of thousands of steelworkers cost steel companies millions of man-days in lost production time. Between 1960 and 1966, the number of man-days lost as a result of strikes oscillated between 10 and 16 million annually. The situation shifted radically in 1967, when work stoppages cost employers 31 million man-days. The figure rose to 35 million man-days in 1968. In 1969 it slipped slightly to 29 million man-days. In 1970 the total man-days lost as a result of work stoppages hit 52.7 million. That was the year of a two-month-long strike of auto workers against General Motors. It was also the year of the massacre by national guardsmen of four students at Kent State University.

Strike levels declined to about 16 million work days lost in 1972 and 1973, in large measure due to the collaboration of the AFL-CIO, Teamsters and UAW on a Government-Management-Labor committee that had been set up to control wage demands. But in 1974, spearheaded by militant coal miners, work stoppages claimed almost 32 million man-days. Strike levels slipped to 17.5 million man-days in 1975. However, for the rest of the decade, from 1976 through 1980, strikes cost employers between 20 and 23 million man-days.

These figures testified to the immense combativity of the working class throughout the 1970s. The high point of class militancy was the national coal miners’ strike of 1977-78. The strikers rejected two sell-out contracts negotiated by the union bureaucracy and defied a back-to-work order issued by President Jimmy Carter, who was acting under the provisions of the notorious Taft-Hartley Act.

A review of this history is necessary in order to appreciate the changes in American society over the past 30 years. This year marks the 30th anniversary of three events that signaled the beginning of a vicious counter-offensive by the ruling class against the working class. The conditions for this counter-offensive had been created by the fact that the struggles of the working class in the 1960s and 1970s, despite their militancy, had lacked any independent political perspective. The alliance of the trade union bureaucracy with the Democratic Party kept the mass movement within the shackles of capitalist politics and capitalist economics. In other words, the movement eventually arrived at a dead end, which provided the ruling class with an opportunity to reverse its retreats of the previous decades and go on the offensive.

The counter-offensive began with the appointment by President Carter, a Democrat, of Paul Volcker as chairman of the Federal Reserve. The Bulletin, the forerunner of the World Socialist Web Site, warned on July 27, 1979, that his appointment signified “a declaration of war on jobs and working class living standards.” This analysis was quickly vindicated. Volcker immediately set about to break the back of working class militancy by raising interest rates to unprecedented levels, thus provoking a severe recession and driving up unemployment. Under Volcker, the prime rate eventually went as high as 21.5 percent.

The second event was the announcement by Chrysler that it would shut down a major production facility in Detroit, the famous Dodge Main plant in Hamtramck that employed several thousand workers. This decision was accepted by the UAW, which ignored demands by rank-and-file workers for action to defend jobs. Opposition was strangled and the factory closed without resistance.

Finally, the UAW bureaucracy decided to grant Chrysler major concessions on wages and work rules. This began a pattern of union-management collaboration that cleared the way for subsequent attacks on the jobs, wages, working conditions, and benefits of all sections of the American working class. All these events took place even before Reagan was elected president. His accession to the presidency in January 1981 accelerated and intensified the war on the working class that Carter had begun in 1979. The defining event of the Reagan presidency—the firing of 11,000 striking air traffic controllers, members of PATCO—sent a signal to all corporations that strike-breaking and union-busting was legitimate and would enjoy the support of the government. However, Reagan’s destruction of PATCO would not have succeeded had he not received the support of the AFL-CIO bureaucracy, which opposed any action in defense of the victimized air traffic controllers.

In the years that followed, the AFL-CIO bureaucracy sanctioned a wave of government and corporate strikebreaking. There were no shortage of strikes during the 1980s—by Greyhound bus drivers, Continental pilots, Phelps Dodge copper miners, Hormel meatpacking workers, and AT Massey coal miners, to name only a few of the best known struggles of the 1980s. But these and virtually every other strike were isolated by the AFL-CIO and defeated. In the case of the Hormel strike, the United Food and Commercial Workers Union decertified the local that was at the heart of the strike.

As they collaborated with the government, the Democratic Party and big business in smashing strikes, the unions entered into explicitly corporatist relationships—modeled on the labor-business syndicates established in fascist Italy and Nazi Germany during the 1920s and 1930s—that espoused unrestrained union-management collaboration. In an action that symbolized its corporatist ideology, the UAW adopted the practice of placing a hyphen between its name and that of the Big Three auto companies, as in “UAW-GM,” “UAW-Chrysler,” and “UAW-Ford.”

After a decade of sabotage, the AFL-CIO, UAW and Teamsters were unions in name only. They had ceased to exist as organizations that were in any way associated with the defense of the working class. Rather, they served the financial and social interests of an upper middle-class stratum of right-wing functionaries, policing workers on behalf of and in collaboration with the corporations.

The most telling statistical evidence of the impact of the corporate-controlled unions on the working class is the virtual disappearance of strikes in the United States. Between 1990 and 1999, there was not one year where even six million man-days were lost as a result of strikes. During the present decade the situation has been even worse. Except for 2000, when 20 million days were lost—as a result of the protracted strike of actors (which claimed more than 17 million days)—strikes in subsequent years (2001-2008) oscillated from a low of 659,000 days lost (in 2002) to a high of 4 million (in 2003). Since 2004, the number of man-days lost due to work stoppages averages out to just about 2 million days annually.

The consequences of the suppression of class struggle by the right-wing bureaucratic labor organizations are seen in the huge growth of social inequality, the stagnation and decline in working class living standards, the emergence of a financial oligarchy that wields unprecedented political power, the erosion of democracy and, finally, the growth of militarism. The reactionary and socially destructive character of economic development within the United States and internationally depended on the intense and active collaboration of the trade union bureaucracy.

However, it must be stressed that this was not a uniquely American phenomenon. Analogous social processes took place internationally. Capitalism survived the immense working class upsurge of the period between 1968 and 1975 due to the betrayals of the labor bureaucracies. The Stalinist and social democratic bureaucracies played, in their own way, no less a reactionary role than the pro-capitalist labor bureaucrats in the United States. The election of Margaret Thatcher in Britain in May 1979 cleared the path for the introduction of free-market policies that mirrored those of the US, and with similar social consequences. And, as in the United States, the labor bureaucracy played the decisive role in suppressive working class opposition to the policies of the right-wing government.

Moreover, the decision of the Stalinist regimes to reintroduce capitalism in the countries they dominated during the post war period had an immense impact on global politics and economics during the last 20 years. The dissolution of the Soviet Union and the reintroduction of capitalism into Eastern Europe opened up enormous new resources for exploitation by the United States, European and Japanese capitalism. Even more significant in economic terms was the reintroduction of capitalism into China by the Stalinist regime. The economic transformation of China into a global center of low-cost manufacturing began in the 1980s. This process generated social conflict that culminated in 1989 with the mass protests of student youth and workers. The massacre that occurred in Tiananmen Square in June 1989 was the decisive event in suppressing popular opposition to the right-wing policies of the Stalinist regime.

The suppression of class struggle in the advanced capitalist countries and the restoration of capitalism in Eastern Europe and China created a favorable environment for the policies associated with the massive growth of the finance industry, laden with debt, during the 1980s, 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century. This was an environment that required the suppression of all restraints—social, political and even legal—on the recklessly speculative operations of capital.

A protracted period of social and political reaction signifies the forcible and artificial suppression of social and economic contradictions. The degree to which these contradictions have been suppressed determines the force and intensity of the crisis that follows. It is, therefore, to be expected that the present crisis will give rise to explosive social upheavals.

During its first 100 days, the Obama administration has devoted its energies to protecting the wealth and interests of the financial oligarchy. The recent surge in the stock market—which began after Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner unveiled the administration’s bail-out plan and gained strength after Obama sanctioned a massive restructuring of the auto industry—reflects Wall Street’s confidence in the White House. The bank bailout, funded by taxpayers, made it clear to the financial oligarchy that no expense will be spared to protect its interests.

Obama’s intervention in the auto crisis further demonstrated that the administration saw the broader economic breakdown as an opportunity to drastically restructure social relations within the United States at the expense of the working class. This is what Rahm Emanuel, Obama’s chief of staff, really had in mind when he said, “Never let a crisis go to waste.” As New York Times business analyst Floyd Norris wrote on May 2:

This may come to be seen as Mr. Obama’s “Nixon in China” moment. Just as it took a conservative Republican to open relations with the largest Communist country in the world, it took a liberal Democrat to break the UAW.

Of course, it is necessary to add the following crucial caveat: Obama hardly had to “break” the UAW. It had long ago ceased to be a union in any socially and politically meaningful sense of the word. The UAW is an organization that serves the interest of a vast administration that bases its income on a parasitic, exploitative and duplicitous relationship with the organization’s membership.

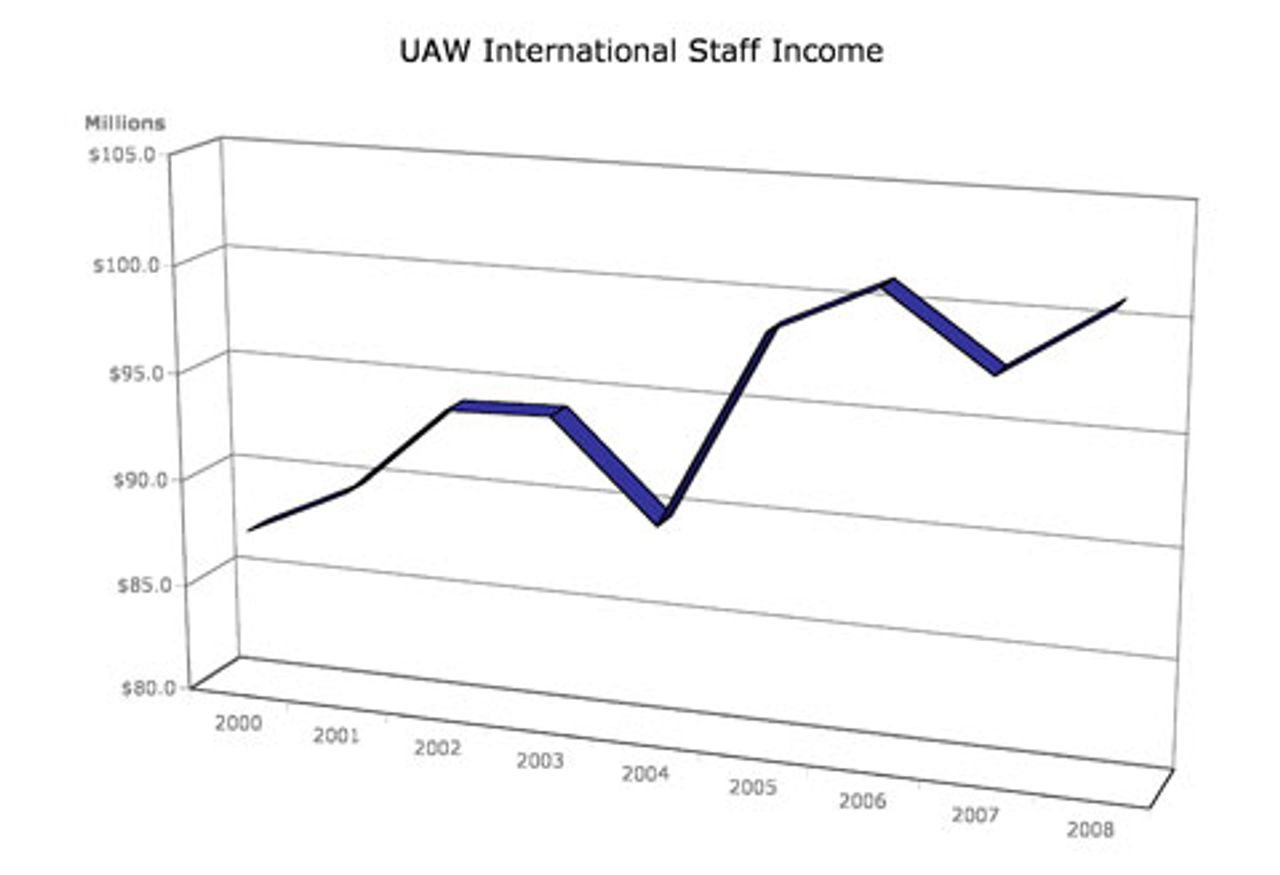

The international headquarters of the United Auto Workers employs more than 2,000 people. The printout of UAW International employees runs approximately 130 legal-size pages. Total disbursements to the staff at the UAW’s International Headquarters in 2008, in the form of salaries, allowances and expenses, were, according to the union’s official financial statement, $101,896,200!

Most of the employees are identified as “servicing representatives,” “organizers,” “stenographers,” and “administrative assistants.” In other words, they occupy sinecures, for which they are required to do nothing more than support the top union executives. Approximately one quarter of the staff is paid over $110,000 per year. Most of the several hundred “servicing representatives” receive salaries and additional cash subsidies that run between $120,000 and $140,000 per year. The typical “servicing representative” is a semi-retired right-wing bureaucrat in his late 40s or 50s from a union local—which, due to factory shutdowns, may no longer even exist—who is “responsible” in some rather vague sense for overseeing contract agreements covering a few hundred union members. A large number of UAW International staff members share blood ties, so it is not unusual to find families that are collectively receiving more than $200,000 annually in union payments.

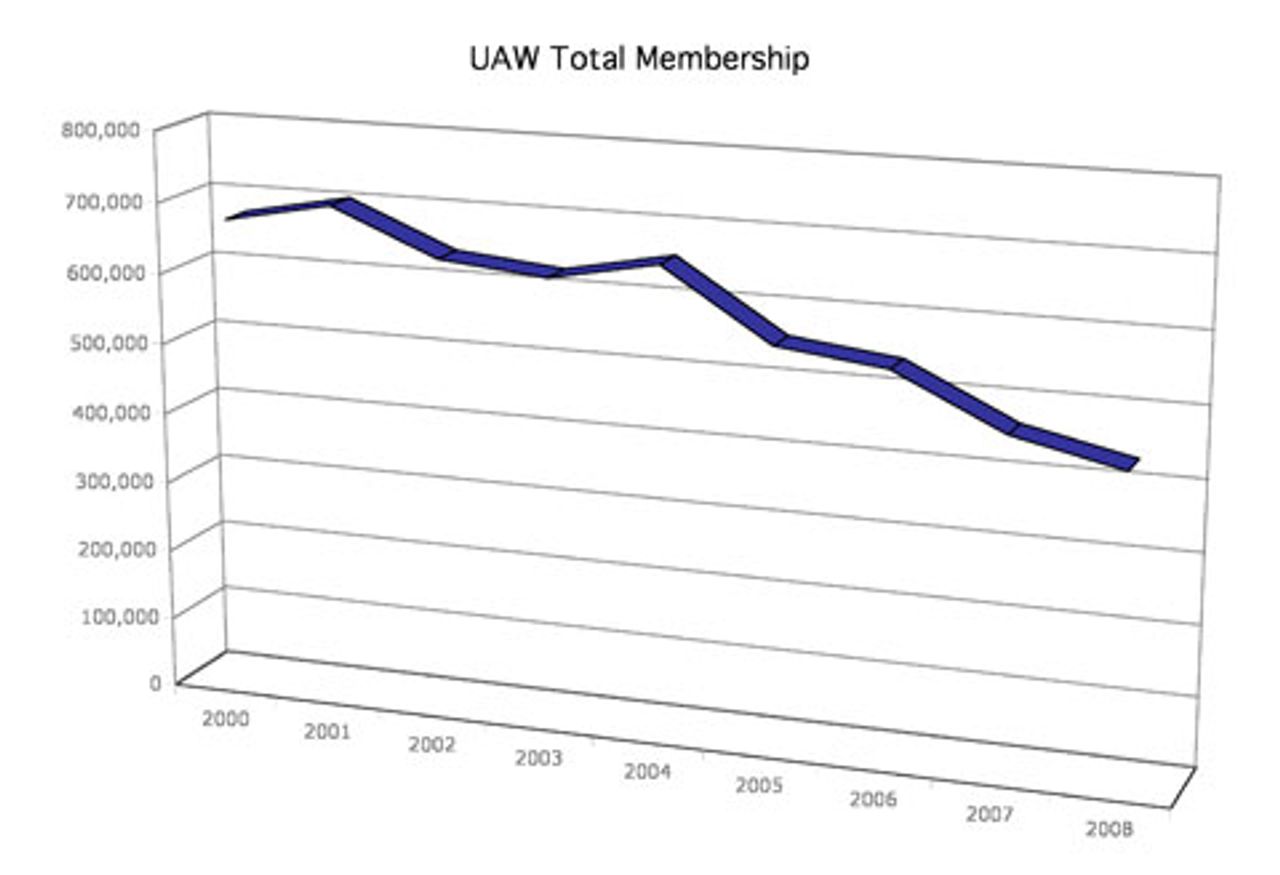

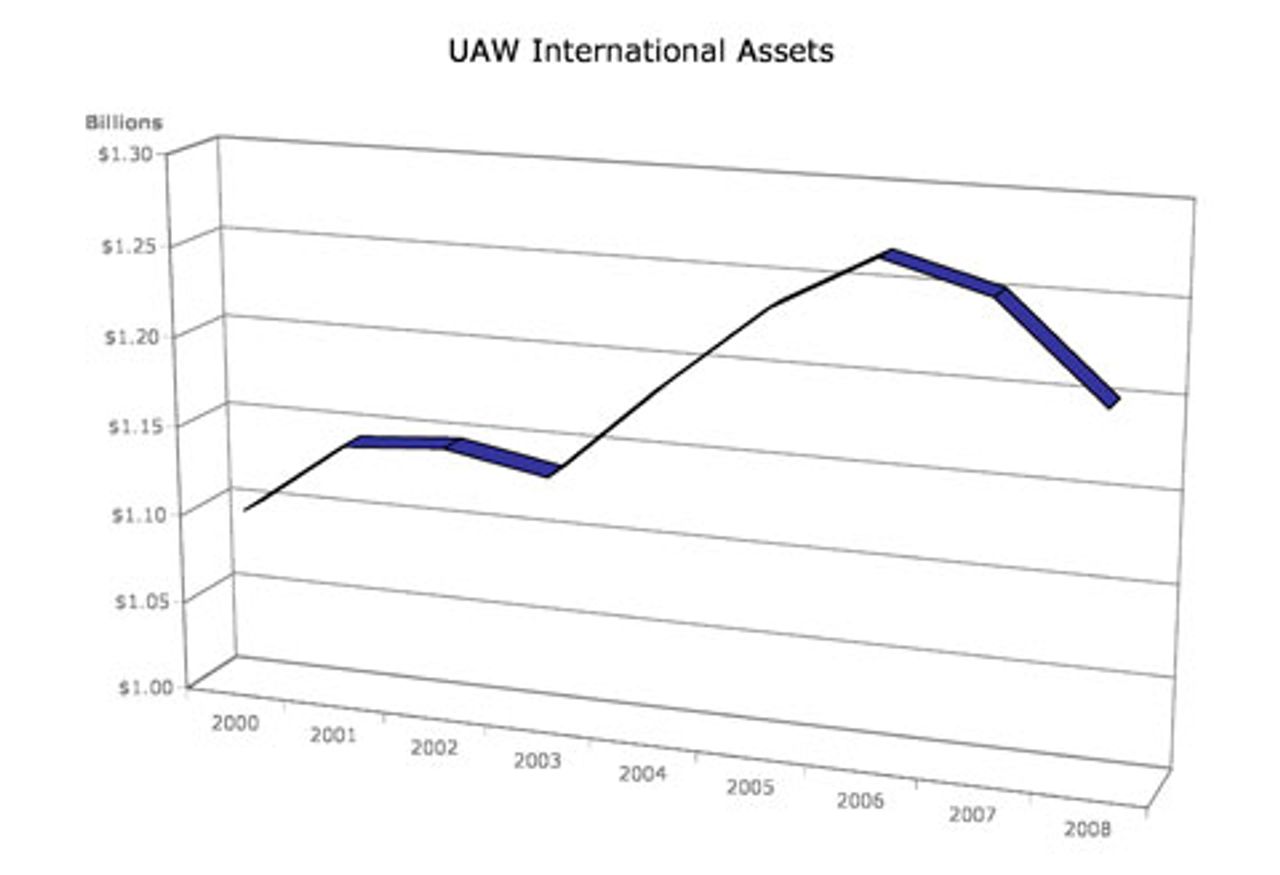

The UAW’s massive loss of membership has had no significant impact on the financial well being of the administration. In 2001, the union had a membership of 701,000 members. Its total assets were appraised at $1.1 billion. By 2008, its membership had fallen to 431,000—a drop of approximately 40 percent.

However, during this same period, the UAW’s assets rose to $1.2 billion.

The increase of assets has made possible a substantial increase in the income of the UAW’s administration. In 2000, the International paid its staff $89.6 million in salaries. In 2008, the salaries had grown to $100.9 million. Looking at these figures in another way, in 2000 the UAW’s central bureaucracy received $133 in income per union member. Just eight years later, the central bureaucracy received $233 in income per union member.

One must keep in mind, as one reviews these figures, that they cover only the staff at the UAW International headquarters. Additional tens of millions are grubbed by the staffs employed by the vast network of local union fleshpots. And beyond the UAW, there are hundreds of other “union” organizations that operate along the same lines, collectively doling out billions of dollars in salaries and benefits to the largest and most expensive corporate-controlled labor-management police force in the world.

Everything that Obama has done has been carried out with the UAW’s approval. The settlement agreement reached between Chrysler and the UAW, prior to the company’s announcement of bankruptcy, includes the following provisions: 1) The cost-of-living allowance is being suspended; 2) Previously negotiated performance bonuses are being suspended; 3) Christmas bonuses are being suspended; 4) Relief time for employers is being substantially cut; 5) The use of temporary employees is being extended; 6) All disputes will be submitted to binding arbitration; 7) Retiree health benefits are being cut immediately.

In the aftermath of Chrysler’s bankruptcy announcement, the UAW is claiming that its close ties with the Obama administration will provide significant protection for Chrysler workers. This is a lie. Again, to quote Norris:

It is said that the United Auto Workers, which supported Mr. Obama in the election last year, is effectively being paid off by treating the bondholders worse than the retirees. I disagree. The retirees may have a little better chance of getting benefits they were promised, but the current workers are getting little more than being allowed to keep some of their jobs.

The open involvement of the UAW in these massive attacks has destroyed what little was left of the credibility of this reactionary organization among auto workers. They understand that they have been betrayed by this organization. The workers’ defense of their basic rights and class interests must and will lead to a rebellion against the UAW and all the other pro-corporate and pro-capitalist organizations. New forms of class organizations will emerge as workers move into struggle against the capitalist system.

We have already reviewed the extraordinary decline in the number of strikes, and of workers involved in strikes, during the past 20 years. The virtual absence of industrial conflict between 1989 and 2009 sets these two decades apart from any other period in post-Civil War America. A review of every decade between the 1870s and 1980s would demonstrate that each of them witnessed significant levels of industrial class conflict. The 1990s and the 2000s stand out in sharp contrast.

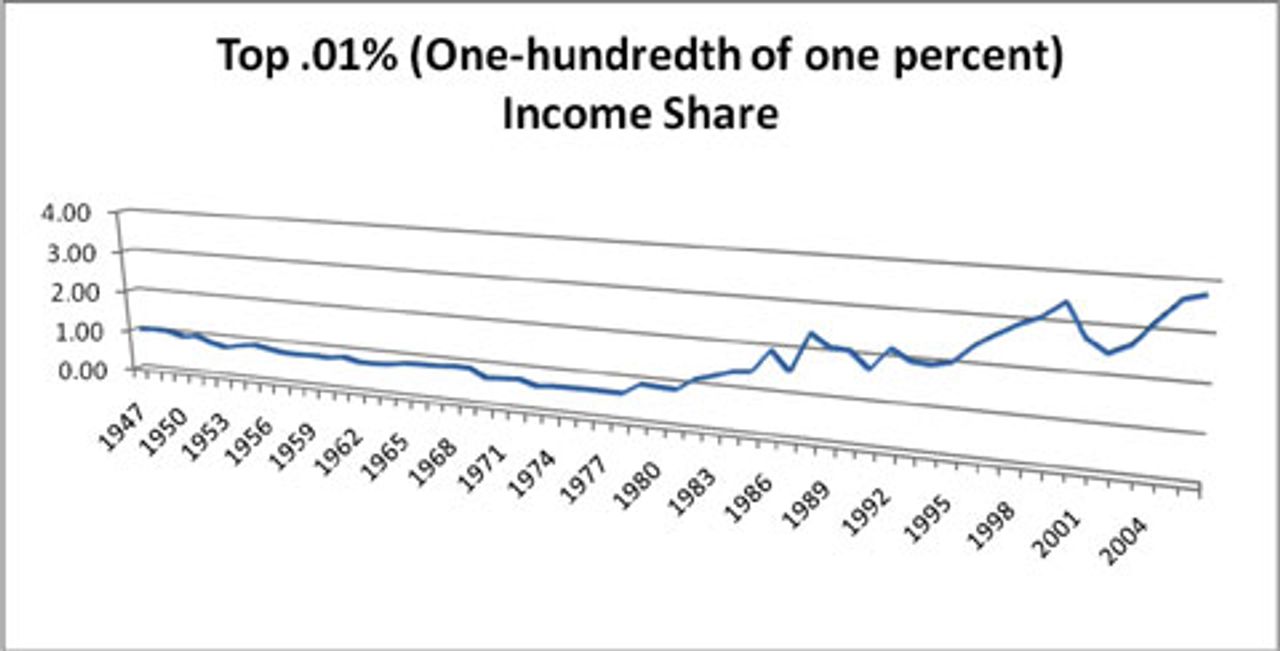

But this anomalous character of the past two decades must be analyzed in the context of another principal characteristic of this period; that is, the staggering increase in wealth accumulation in the very richest sections of the American ruling class. In 1947 the richest .01 percent of the population claimed 1 percent of the national income. This was significantly less than the 3.61 percent of the national income that it claimed in 1929, prior to the Wall Street crash. The intervening years had been marked by violent class conflict and the rise of the Congress of Industrial Organizations. By 1973 the income share of the richest .01 percent had declined to 0.6 percent of national income. This low point was a consequence, above all, of the preceding two and a half decades of consistently high levels of class conflict.

This process began to move in the opposite direction—toward an ever-greater concentration of wealth in the richest .01 percent (and, in fact, in the wealthiest 5 percent) from 1979 on. In that year, the richest .01 percent garnered 0.9 percent of the national income. By 1989 its income share had risen to 2.3 percent. By 1999 the income share of the top stratum reached 2.92 percent. By 2006, the last year for which we have figures (based on the studies of Professors Piketty and Saez), the income share of the richest Americans had reached 3.76 percent.

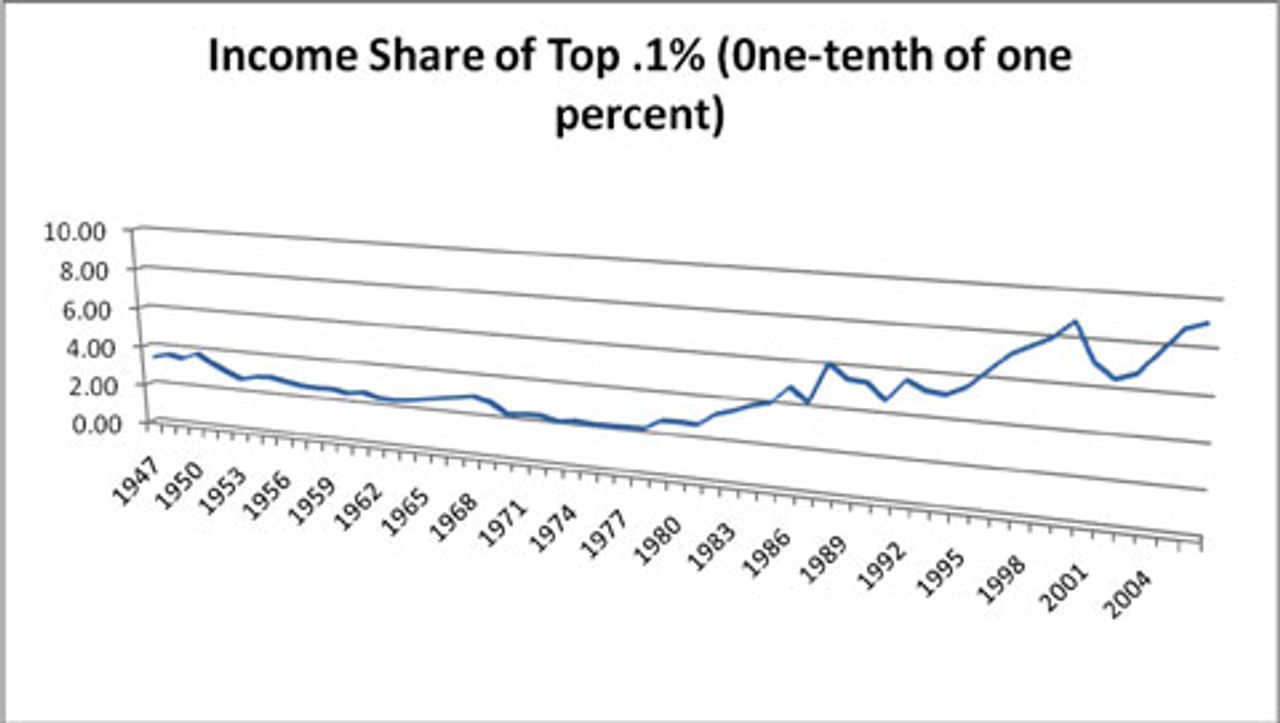

If we now examine the income share of the top 0.1 percent (one-tenth of 1 percent) of the population, this layer garnered 8.7 percent of the national income in 1929. By 1947 its share had declined to 3.4 percent. At its low point in 1973, its income share had fallen to 2.2 percent. In 1979 it had risen to 2.7 percent. In 1989 its share had leapt to 5.5 percent. By 1999 it had reached 8 percent. In 2006 the income share of the top 0.1 percent stood at 9.1 percent.

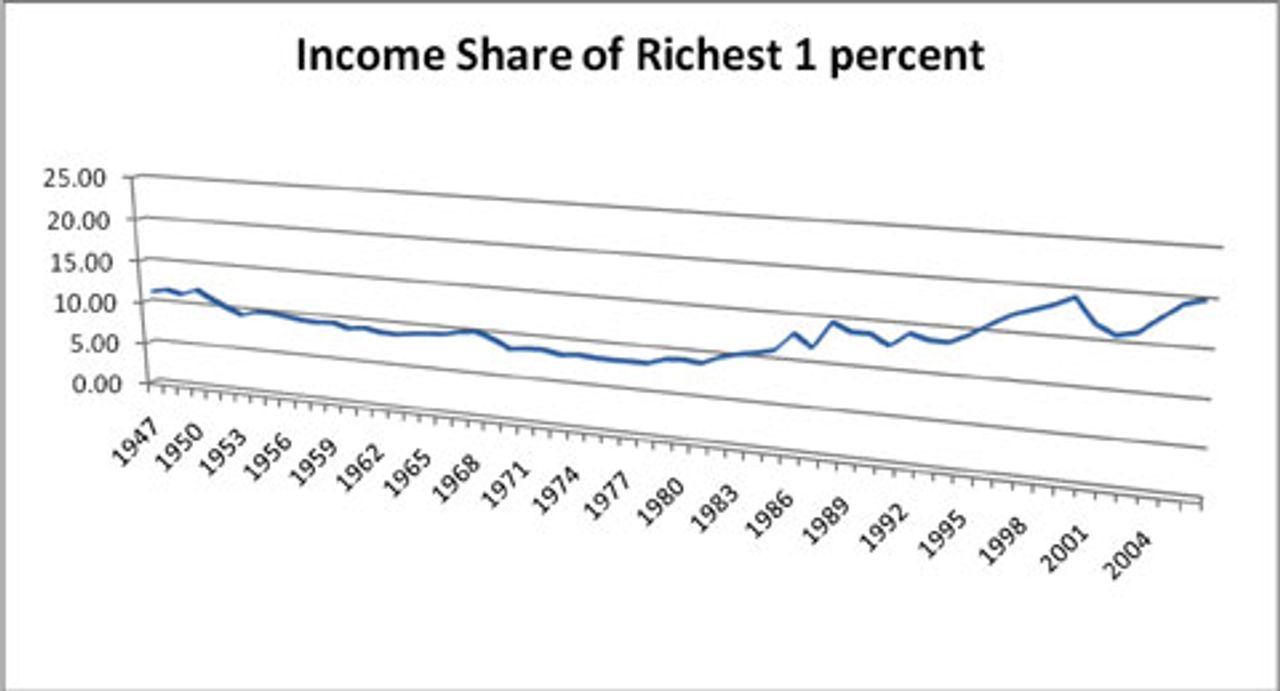

Finally, let us look at the income of those who comprise the top 1 percent. In 1929, this stratum received 19.8 percent of the national income. In 1947 its share had dropped to 11.25 percent. In 1973, the low point, its share of national income was 8.3 percent. By 1979 it had risen slightly to 9 percent. By 1999 its share had more than doubled to 18.4 percent. And in 2006 it stood at 20 percent. That is, the richest one percent of the population received one fifth of the national income.

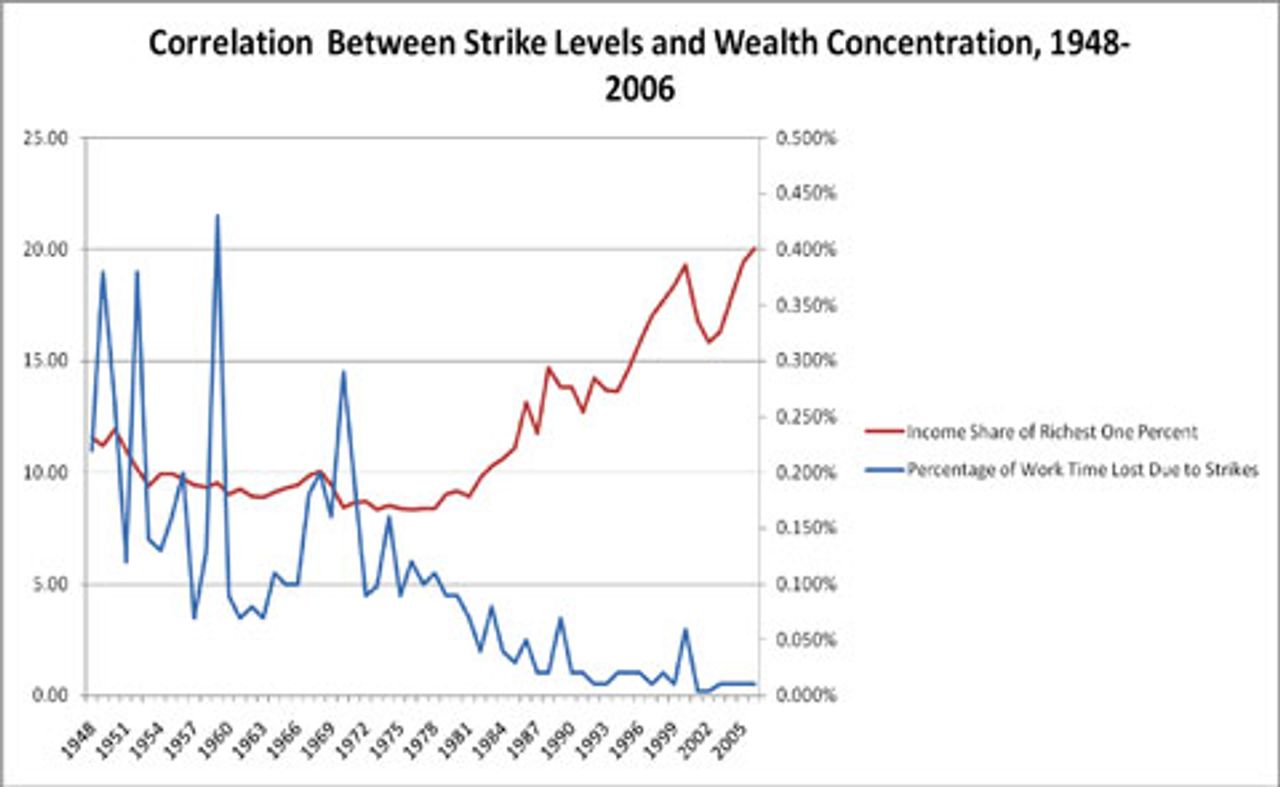

When the graph of the income share of the wealthiest section of the capitalist class between 1947 and 2006 is superimposed on the graph of strike levels during the same period, the relationship between these variables is vividly illustrated. High levels of workplace militancy and open class conflict are associated with a decline in wealth accumulation among the rich and of social inequality. Under conditions in which social conflict is suppressed, wealth accumulation increases rapidly along with the level of social inequality. As the graph of these related phenomena demonstrates, the gap between the lines of wealth accumulation of the richest .1 percent and the level of strike activity has grown dramatically during the past 20 years.

This gap—which can be defined as a potential “zone of conflict”—has reached dimensions that are not compatible with social “peace.” In terms of social inequality, the United States is now back to where it was in 1929, prior to the Great Depression and the ensuing social upsurge of the working class. There are limits to the ability of the Obama administration and the trade union apparatus to suppress social conflict. The social contradictions of the United States have reached a point where an explosive renewal of the class struggle is unavoidable.

But the coming struggles will not merely repeat the patterns of the past. At the beginning of the year, the SEP stated:

The tasks of the SEP proceed from the logic of the socioeconomic and political crisis of American and world capitalism. The party anticipates that the deepening crisis will lead to the social and political radicalization of the working class in the United States and internationally. This radicalization will find expression in the development of mass struggles that strive to break free of the bureaucratic shackles of the reactionary trade unions and assume an increasingly political and anti-capitalist dimension.

History has once again taken a sharp turn. The past 12 months have witnessed an extraordinary transformation of the objective situation. Mankind is entering into a new period of political upheavals and social struggles, on a world scale, which will decide the fate of humanity. The objective prerequisites for world socialist revolution are emerging with extreme rapidity. Thus, the role of the subjective factor, the revolutionary party, assumes decisive historical significance. The chasm between the maturity of the objective situation and the present consciousness of the working class must be overcome. This requires, above all, the recruitment of workers and youth into the SEP and their political education on the basis of Marxist theory and the history of the Fourth International. This is the task to which the International Committee of the Fourth International and the Socialist Equality Party must direct all its efforts in 2009.

Nothing that has occurred during the past five months leads us to believe that this analysis and perspective should be revised. Rather, the single-minded and unrelenting efforts of the Obama administration to resolve the crisis in the interests of the financial oligarchy will exacerbate class tensions. Whatever the immediate impulse for the renewal of open class conflict, its form, character and goals will, in the final analysis, be determined by the advanced stage of the crisis of American and world capitalism. The coming battles of the American working class, unfolding as part of an emerging movement of the international working class, will assume the form of a political struggle for power and for socialism.