Joseph McBride

Joseph McBrideThis is the first part of an interview with Joseph McBride, author of What Ever Happened to Orson Welles? A Portrait of an Independent Career(2006). The second part was posted June 17.

While in the Bay Area for the recent San Francisco Film Festival, David Walsh and Joanne Laurier had a lengthy conversation with Joseph McBride, author of What Ever Happened to Orson Welles? A Portrait of an Independent Career (University Press of Kentucky, 2006), an unusual and valuable book.

McBride, an associate professor at San Francisco State University, is a former screenwriter, a former critic and reporter for Daily Variety in Hollywood, and one of the foremost experts on American filmmaker Orson Welles. He has also written or edited works on John Ford, Howard Hawks, Frank Capra, Steven Spielberg and Kirk Douglas.

What Ever Happened to Orson Welles? is significant for a number of reasons. The title refers sardonically to the attitude of numerous critics toward Welles’s last years, the two decades, more or less, before his death in 1985 at the age of 70. In their complacency and indifference, such commentators choose to view Welles as a victim of his own unfortunate career choices or a supposed inability to finish projects, or, worse still, they paint him as a lazy, overweight “has-been” who had tragically squandered his undeniable talent.

According to this theory. Welles’s career following the making of Citizen Kane when he was 25, in 1941, consisted of a series of self-inflicted disasters that resulted in his becoming, more or less deservedly, something of a pariah.

Orson Welles in the 1980s (photo: Gary Graver)

Orson Welles in the 1980s (photo: Gary Graver)McBride works diligently to dispel such myths. He knew Welles during the last 15 years of the latter’s life and participated in one of the filmmaker’s major unfinished projects, The Other Side of the Wind, about an aging Hollywood director, with John Huston in the lead role.

The author makes clear that Welles was willing and eager to work, virtually to the last day of his life. The fundamental sources of his difficulties remained what they had been throughout his career: the financial and artistic constraints bound up with working in the American film industry

McBride writes: “The story of the last fifteen years of his life is a saga of untiring work, dedication, creativity, and indomitable courage in the face of overwhelming obstacles placed before him by a society that tragically undervalues its great artists.” (p. 26)

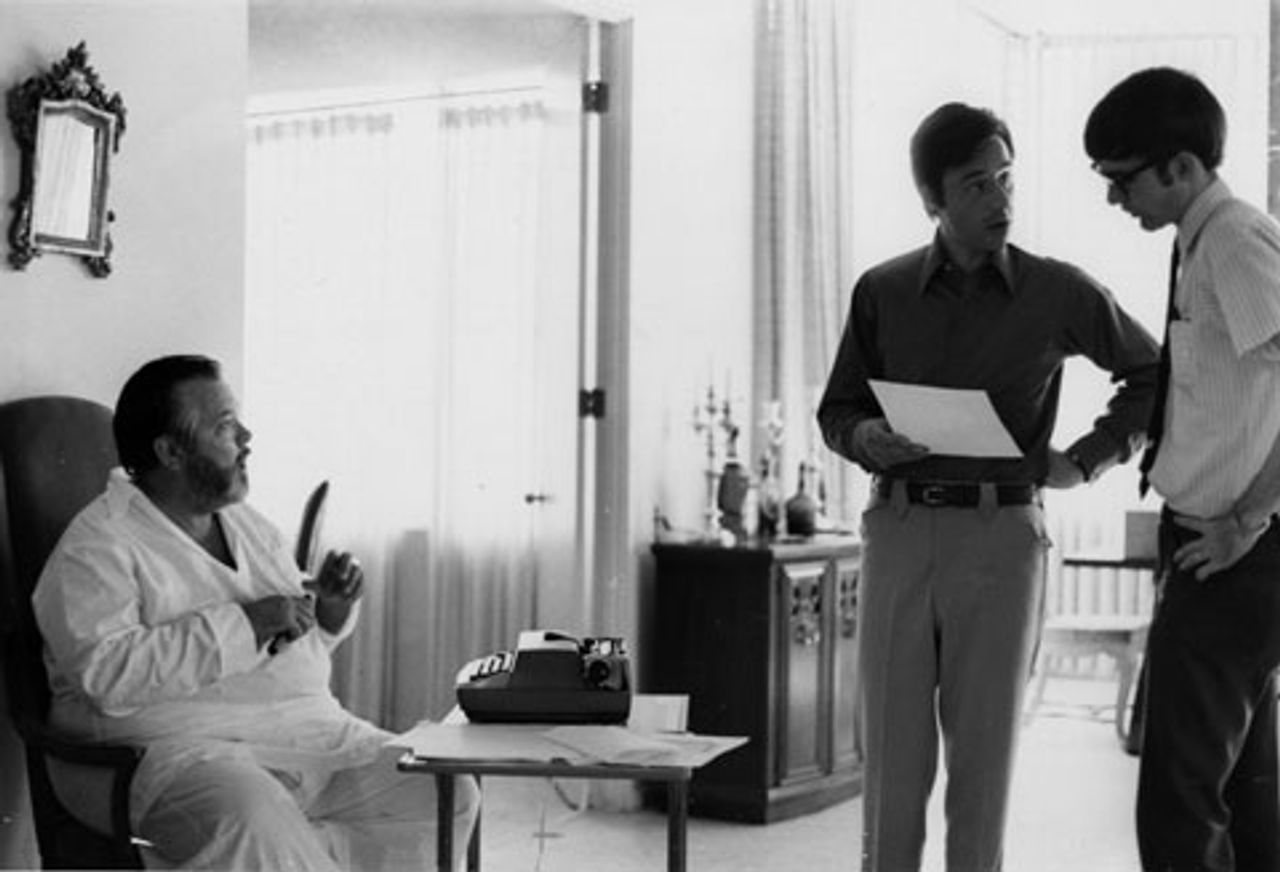

Orson Welles, Peter Bogdanovich and Joseph McBride rehearsing The Other Side of the Wind in August 1970

Orson Welles, Peter Bogdanovich and Joseph McBride rehearsing The Other Side of the Wind in August 1970In addition to The Other Side of the Wind, McBride discusses a number of the projects that Welles worked on and was unable to complete in the last several decades of his life, including his nearly 30-year, legendary effort to adapt Cervantes’ Don Quixote for the screen; various planned series for US television, including a documentary “essay” show called “Orson Welles and People”; a thriller, The Deep, with Jeanne Moreau; a version of The Merchant of Venice, whose negative was stolen from Welles’s Rome office; The Dreamers, an adaptation of two stories by Isak Dinesen; scripts adapted from works by Joseph Conrad and Graham Greene: “a cheerily autobiographical account of his early days in the theater”; and many others.

What Ever Happened to Orson Welles? sets the record straight in another important regard. It emphasizes Welles’s artistic and political radicalism, which has been downplayed by numerous biographers, in some cases with Welles’s own help. As McBride notes, “Despite Welles’s later defensiveness about his political evolution and his general aversion to polemics on stage or screen, his artistic career...was always profoundly radical.” (pp. 46-47)

The book argues convincingly that Welles was blacklisted by the Hollywood studios in the late 1940s. McBride points to “unmistakable evidence, hidden in plain sight, that Welles’s political and cultural activities had caused him to be blacklisted during the postwar era. His decision to leave the country in 1947, just as the Hollywood blacklist was being imposed, and his reinvention of himself as a wandering European filmmaker, largely out of necessity, hastened his already strong bent toward independence from the commercial system.” (p. xvii)

Welles was a man of the left, who associated with socialist-minded intellectuals in the New York theater world before his move to Hollywood in 1939. His direction of a version of Macbeth set in Haiti in 1936 for the Federal Theatre Project’s Negro Theater Unit, and Marc Blitzstein’s left-wing musical work, The Cradle Will Rock, and an adaptation of Julius Caesar laid in fascist Italy, both in 1937, consolidated his reputation as a remarkable dramatic innovator and a fierce critic of contemporary society.

William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph HearstWelles had already incurred the wrath of right-wing publisher William Randolph Hearst for his theater and radio work, but his audacity in choosing to direct a film for RKO that drew its inspiration at least in part from the media mogul’s life and career, Citizen Kane, made him, in the words of an artistic associate, “a marked man.”

Attacking Hearst and all that he represented within the American ruling elite, in McBride’s words, brought down “the wrath of a whole powerful network of right-wing red-baiters, including the FBI, the Dies committee, and the American Legion, all of which were allied with and supported by the vociferously anti-Communist publisher.” (p. 45)

J. Edgar Hoover

J. Edgar HooverThe FBI opened a file on Welles in April 1941, shortly before Citizen Kane’s release, and kept it active until 1956, when the filmmaker was safely semi-exiled in Europe. Hearst had been an ally and collaborator of J. Edgar Hoover since the early 1930s, supplying him with information on suspected Communists and fellow travelers in Hollywood.

McBride cites an FBI report’s conclusion about Welles’s extraordinary first film: “The evidence before us leads inevitably to the conclusion that the film Citizen Kane is nothing more than an extension of the Communist Party’s campaign to smear one of its most effective and consistent opponents in the United States [i.e., Hearst].” (p. 45)

The hostility of Hoover and the FBI toward Welles was so great, that although the bureau’s agents could find no proof of his membership in the Communist Party (and it appears he never was a member), “Los Angeles special agent in charge R. B. Wood took the drastic step of recommending to Hoover in November 1944 that Welles be listed as a Communist on the FBI’s Security Index. That little-known roster gathered the names of people who supposedly represented threats to national security. Originally the Custodial Detention Index, it was designed by Hoover to facilitate the rounding up and detention of alleged subversives during a national emergency. Welles’s name was on the Security Index from 1945 to 1949.” (p. 50)

As we note in our interview with McBride, it has some significance that an individual often credited with directing the greatest film made in the US was placed on a list of those to be rounded up and interned when the powers that be felt threatened!

McBride’s book has many fascinating aspects to it. We spoke to him at his home where we discovered him surrounded by piles of books, videos and DVDs.

* * * * *

Citizen Kane

Citizen KaneWSWS: We found your book while searching for material on Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane [1941]. We thought it was especially significant that you emphasized Welles’s political radicalism, and also challenged the conventional wisdom that his career was a downward spiral from Citizen Kane. It’s a valuable book with some remarkable insights. There are big questions bound up with his career, which are not just film questions, but bound up with the character of American society in the middle and late 20th century. They continue to vibrate.

Joseph McBride: Welles may be a beneficiary of the changing times. In the 1970s, when the blacklisted people started getting a lot of attention, they were now seen as heroes. The whole thing reversed itself. With Welles, people have mistakenly rejected the idea that he was blacklisted.

Have you seen his FBI file? The main file is 222 pages long. You can get it online.

One of the problems with the history of the blacklist is that there’s sort of an official list that everybody knows. These are people who were unfriendly witnesses before HUAC [House Committee on Un-American Activities], basically. People are familiar with them. Dalton Trumbo, John Howard Lawson and the others.

But there were so many people who were “greylisted” and blacklisted who you don’t really know about. And that’s part of the Kafkaesque nature of the blacklist. Sometimes people could not even tell what happened to their careers because suddenly they just couldn’t get work.

James F. Byrnes, the former secretary of state [1945-47] under Harry Truman and chief legal counsel for the studios, advised the film industry to deny there was a blacklist because blacklisting was illegal.

There’s a documentary called Hollywood on Trial, made in 1976, and Ronald Reagan is in it, sitting in front of an American flag and a California flag and wearing makeup. On camera Reagan says there was no blacklist. It’s sort of like Holocaust denial. It’s terrible to go through it, and then another blow is to be told it didn’t exist.

There are a lot of people like African-American actress Hattie McDaniel [who won the award for Best Supporting Actress for Gone With the Wind in 1939], for example, somebody who I admire a lot, who were greylisted. But she suffered after the war because she was progressive. And she was also suffering because people in the NAACP and other liberals were criticizing her for the kind of roles she played. She was kind of unemployable for a while because she was getting it from both sides. But very few people know that she was blacklisted or greylisted. So when you do the research, you start finding out that people had these degrees of problems. Some were totally blacklisted and some simply didn’t find much work.

So with Welles, I realized that this was the elephant in the room that nobody ever really talked about. The clearest evidence that he was blacklisted is that he was named in Red Channels, that terrible book put out in 1950. I’ve read the book, and it lists a lot of people in the business, and if your name was in Red Channels, you had to write a letter clearing yourself or do some other form of clearing yourself to work again. That’s the way it worked.

I’ve seen the types of letters that people wrote, for example, screenwriter Philip Dunne. He was a liberal and an anti-communist, and one of the founders of the ADA [Americans for Democratic Action], and he was also a founder of the Committee for the First Amendment. They fought the blacklist and then they sort of caved in—it was short-lived. He showed me a letter he had to write, even though he was not a Communist. He had to state that and disown some of his associations. He felt bad about it, but he showed it to me. Dunne was working for Twentieth Century-Fox, but for most of the studios you had to do something like that.

And John Houseman mentions in his memoirs that he had to write a letter like that. He was Welles’s partner in the Mercury Theatre. So the things they held against Houseman were some of the same things they held against Welles. Associating with left-wingers, putting on certain plays—The Cradle Will Rock [1937]—and things like that.

So I would assume that Welles, in order to do even the limited work he did for American television and for Hollywood studios during the 1950s, would have had to write a letter of that sort, short of informing on people. If you were not a Communist you might not have to inform on people to go back to work, if you were abject enough in your letter and you had people in the studios supporting you. I could not imagine that Welles would ever have informed on people.

When I was researching my recent book on Welles, I began thinking about when he left Hollywood. Most of the books say that he left in 1948 and did not come back until the mid-1950s, and that’s pretty much the heyday of the blacklist.

In his FBI file, they reported he left Hollywood in late November 1947.

WSWS: A significant month. The “Hollywood Ten” were cited for contempt, and the studios launched the blacklist in November 1947.

JM: Yes. The original Hollywood Nineteen were subpoenaed in October 1947 for the November HUAC hearings involving those who became known as the Hollywood Ten.

WSWS: The significance of Welles’s departure in November had never occurred to us till we read your book.

JM: It’s a revelation, thanks to the FBI files. Whatever he had to say publicly about the blacklist I have in my book. He gives a limited mea culpa to blacklist ringleader Hedda Hopper that is fascinating and painful to read. There is an interview with British talk show host Michael Parkinson, from the 1970s, in which he was asked directly whether he went to Europe because he was being investigated. Welles denies it and sort of dances around the subject. But I don’t believe that. He says the reason he went to Europe was not political, it was because he was not getting work in America.

Now it was true that he had just made Macbeth [1948], which was considered a monumental flop. It’s a fine film, but people were dumping on it. The Lady from Shanghai, which actually did not come out until 1948, was also a commercial failure. So he was getting to the point where it was hard to find a job as a director. But, theoretically, he could have worked as an actor.

There’s a book on Carol Reed’s The Third Man—which came out in 1949—that mentions David O. Selznick, one of the producers, and his resistance to hiring Orson Welles as Harry Lime. Selznick made a comment to the effect that Welles’s politics were a problem in America. To have him in a film would turn people off, etc. The British producer and director went ahead and put him in the film anyway. And it didn’t seem to hamper the film’s release.

The argument against his being on a blacklist was that he did appear in films that were shown in American theaters. So he may not have been totally blacklisted. The American Legion in those days used to threaten to picket theaters. It scared the studios. It’s one of the reasons that they instituted the blacklist. The fact that the Legion didn’t picket Welles’s films does not necessarily indicate that he was not blacklisted.

The other thing you could say is that he did work for some American studios in Europe. Twentieth Century-Fox made some films in Europe in which Welles acted. And Darryl F. Zanuck was his friend and actually put some money into Othello [1952]. So, again, the blacklist may not have been total in that sense.

Welles stayed away until 1953, and what happened then was interesting. He went to work for CBS doing the television version of King Lear, with Peter Brook directing. There was a pattern: Welles appeared on a number of American television shows over the next three years—all for CBS. Sometimes you would have one network that would hire you, and you somehow worked it out with that network and they would support you. You did whatever you have to do to work for them.

WSWS: You suggest he might have had to write a letter to do that?

JM: I think it is almost certain that he would have had to do that, but I haven’t found such a letter. When you take account of other people’s histories, it would have been difficult for him to work under that cloud without it. Now, in his FBI file there is a document that specifically says, “No record of Communist Party membership but Subject has consistently followed Communist Party line.” There’s a lot of innuendo in there and people say, “we think he’s a Communist,” but we, the FBI, really looked for the proof and didn’t find it. And they admit that in the file. So there’s no doubt. Even they knew he was not a Communist. He was very anti-Stalinist.

Welles claims over the years and in various interviews that the Hollywood Communists didn’t like him. I guess because he wasn’t controllable. They felt he was too much of a maverick for them. At least that’s his version.

This next story is a bit off the track, but it’s strange. I interviewed the actor Eddie Albert, whose actress wife, Margo, was blacklisted. So they were leftists. He told me an amazing thing that I don’t think has ever been printed. Albert said that in the latter part of World War II, Ronald Reagan approached the Hollywood Communist party and tried to join.

WSWS: In Paul Buhle’s and Dave Wagner’s Radical Hollywood, they mention that the FBI considered Reagan to be in or around the CP periphery.

JM: Reagan was considered a liberal, and in his testimony before HUAC he says being a Communist was not illegal, and publicly at that time he opposed the blacklist. However, privately, he was informing to the FBI. So he was playing a double game by that time. Eddie Albert said that Reagan tried to sign up with the CP, but they wouldn’t have him, because they thought he was an infiltrator. How history would have been different had Reagan been a Communist!

Welles had never been a Communist, and as one of the blacklisted people told me about Frank Capra, he could not have informed with much specificity on people because he wasn’t a Communist. So Welles probably wasn’t the kind of guy that they would haul before HUAC. Welles was never a Communist, and that was frustrating for J. Edgar Hoover, because he couldn’t pin that on him.

I did a book on Frank Capra [Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success, 1992/2000] that deals extensively with the blacklist. The major revelation of that book was that Capra was an informer during the blacklist era, which was quite stunning. He named names in private.

The Army-Navy-Air Force Personnel Security Board was investigating Capra because he was a member of a think tank for the Defense Department, planning strategy for war in Europe if there were a Third World War. Capra was involved in that, so his security clearance was denied, and a number of things were held against him. He had worked with a lot of left-wing writers, for example. So he panicked and turned in several of his writers, including Sidney Buchman, who wrote Mr. Smith Goes to Washington [1939], and who was a Communist when he wrote that film.

Capra, I also found out, was an FBI informer and a State Department informer. They called him to clear or not clear people in Hollywood. The book took a lot of research, and I came up with the whole story. So I did a lot of investigation of the blacklist and interviewed people who were affected. Ian McLellan Hunter was a blacklisted writer informed on by Capra. I told him that Capra had informed on him, and he was stunned to find that out.

WSWS: Is a 222-page file, as the FBI had on Welles, particularly thick or thin?

JM: It is substantial, but not as huge as some. Charlie Chaplin’s is more than two thousand pages long. Welles’s file indicated serious interest in him. The FBI pursued him and spied on him from 1941 to 1956, when they closed the file.

The file was opened in 1941 around the time of the release of Citizen Kane, and it’s clear that [William Randolph] Hearst, who was a close ally of Hoover’s, had sicced the FBI on him.

Welles was involved in a group for radio called the Free Company, made up of progressives who were doing programs about civil liberties and similar issues. And Welles did a radio show that he wrote and directed called His Honor the Mayor, which is quite sophisticated because it’s about a town in which there is a fascist organization, kind of like the Ku Klux Klan, and the mayor defends their right to freedom of speech and freedom of assembly.

Welles is saying in America we can’t deny anyone the freedom of speech whether we like their politics or not. It was a clever of way of defending basic rights even for our enemies. But Hearst saw through this and didn’t like it—also in the play, they criticize a powerful publisher, it’s implied that he’s a fascist. And it’s clearly Hearst they’re talking about, even though the character has a different name. So Hearst went bananas and attacked Welles over that and, of course, Citizen Kane, so this led to the FBI starting their investigation of Welles.

WSWS: What does it say about American society that the man who directed what is often called the greatest American film [Citizen Kane] was put on the Custodial Detention Index, an FBI list of people to be interned in case of a national emergency?

JM: Having read these files I knew he was on the list. And a story came out after my book was published that Hoover wanted to round up the people on the Security Index, as it was then called, at the time of the Korean War.

WSWS: Yes, we wrote about that in 2007 [FBI’s Hoover proposed internment of 12,000 “disloyal” Americans in 1950].

JM: [President Harry] Truman said no. Because Welles had left the country, the FBI removed him from the Security Index in 1949. But if he had been in the country when the Korean War began in 1950, he probably would have been vulnerable to being rounded up. And winding up in a camp.

WSWS: In the recent review of Hollywood’s Blacklists [The anti-communist purge of the American film industry], we argued that Welles, through no fault of his own, was not prepared for the counter-offensive against him and the left in general.

JM: By 1941 he was prepared, because he was getting the full heat. I think he was a little naïve when he made Kane. It was not a mistake to do it. Some people said he should not have made Kane because it ruined his career

WSWS: Of course, that’s a coward’s argument. That’s the theme of that documentary, The Battle over Citizen Kane [1999] [PBS documentary: “The Battle Over Citizen Kane”—A revealing look at an old controversy]

JM: That was ridiculous, because it equated Welles and Hearst—a progressive and a quasi-fascist—as if they were similar creatures. I think Welles did not realize how much trouble he’d get into by attacking Hearst. That’s one of the reasons Citizen Kane is a wonderful film, it’s very brazen and audacious. But it certainly caused him immense trouble. By the time the film was under attack in 1941, he certainly was aware of the magnitude of the problem, because they were threatening to burn the film.

WSWS: It was a remarkable moment, when Welles persuaded the film studio executives and their lawyers, in a projection room at Radio City Music Hall in New York, not to destroy the film.

JM: [Welles’s editor at the time and future director] Robert Wise, who was there, gave me a first-hand account. He said it was the greatest performance Welles ever gave, when he gave this wonderful speech about defending freedom of speech against fascism and how we have to defend it here at home. It is under attack around the world, he said.... It’s very moving—and the people he addressed his speech to were the heads of the New York corporations that ran the studios and their top lawyers. RKO was threatened by Louis B. Mayer, who ran MGM. He was heading an informal group from the studios and saying we’ll go to RKO and buy Citizen Kane for $800,000 and burn it.

All the studios, who got their lawyers involved, were all feeling vulnerable because Hearst was threatening to go to town against them. He was threatening to bring up the fact that many Hollywood executives were Jews. In Hearst Over Hollywood, Louis Pizzitola [An interview with Louis Pizzitola, author of Hearst Over Hollywood] goes into detail about the anti-Semitic crusade Hearst was going to mount, and he was also going to reveal a lot of scandals about studio bosses and stars. Screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz was quoted about that—Hearst had all the goods on people throughout the years that he had suppressed, various “dirty secrets,” and he was going to publish that material. So the fact that Welles could persuade them is pretty extraordinary.

The fictional version of the struggle over Citizen Kane, RKO 281 [1999] [How today’s film industry views Orson Welles] has that scene, but they ruined it for me. In their version Welles gives that speech and it’s pretty stirring, then he walks out with George Schaefer, the head of RKO. It leaves some ambiguity as to whether Welles meant what he said, or he was just putting on an act, which I thought was a gratuitous pulling the rug out from under this wonderful moment. It’s absurd, because, first of all, Welles was trying to save his film, and, second, he cared deeply about fascism and freedom of speech.

WSWS: Your book points out, without covering over his weaknesses and failings, the ongoing effort to portray Welles as crazy, maniacally egotistical, reckless, wasteful, opportunist, etc. There’s the Tim Robbins version of this in Cradle Will Rock [1999], and, more recently, Richard Linklater’s Me and Orson Welles [2008]. It’s unfortunate. He represents something people still find threatening in some way.

JM: In Discovering Orson Welles, Jonathan Rosenbaum argues that Welles represents the artist, and artists threaten the status quo. Welles is the archetypal troublesome artist. Rosenbaum thinks this is the root of all this. In a puritanical culture the artists are considered amoral and reckless. They waste money, chase women and they do all these terrible things, and Welles seems to fit all those characteristics.

In my book, I point out that Welles went over budget a few times, not a great deal and not as much as others have done. The Lady from Shanghai went way over budget.

Let’s put it in perspective: In regard to his Brazilian film, It’s All True [shot in 1942], which was never completed, there were rumors that Welles went down there and went way over budget. They fired him. They lied about it.

In my book I reproduce the transcript of the phone conversation between two RKO executives, Reg Armour and Phil Reisman. This is a smoking gun. It shows the character assassination that was going on. Armour said, “We don’t want him to know” what the real budget is, because Welles was well under budget. They also said things like, well, he didn’t have a story. They sent him down there without a script because that was the project—he had to discover what the film was about when he was down there. He did do some carousing, there is no doubt, but that’s been kind of exaggerated.

He dated Brazilian women, and you still find the suggestion in some of the books on him that there’s something wrong with that. There’s a kind of racist tinge to this, that he’s reveling with “native women”—they use phrases of that type.

Rosenbaum and Robert Stam argue that Welles’s problems were partly racial or political, because he was taking the side of the poor blacks in Brazil living in the favelas. They were persecuted and economically deprived, and he was centering a lot of the film on their problems and how the government was oppressing them. So he was threatening to the Brazilian and American governments who didn’t want a film of that kind but an innocuous travelogue.

The studio also worried that if the film had a lot of black people in it they couldn’t show it in the South. When MGM used to make movies with Lena Horne they used to design her scenes so they could be cut out when the films were shown in the South. But Welles had whites and blacks freely mixing in the cast. He was under attack for the political content and also because he was associating with black people. He had black members of his creative team whom he would meet with. Granted, they often met in nightclubs. The fact that they were working was ignored. So it’s a lot of picking and distorting of facts, and when you analyze these myths most of them collapse. Or all of them collapse, actually.

WSWS: There’s that aspect of it. But it was not simply the artist as artist in Welles who was threatening. He thought about and deeply criticized American life.

JM: The Magnificent Ambersons [1942] was quite radical when you consider that it’s a film directed against the automobile. Against capitalism to a certain extent. The industrial age that ruined America. Although you could find something quite conservative in that film because it is also a lament for a vanished time in American history.

WSWS: It was directed against Henry Fordism perhaps.

JM: Ambersons was made at the worst possible time because the whole country was gearing up for the war effort. Everybody was supposed to be working 24-hour shifts at the factories and everything else. He comes along and says the automobile, or the automobile industry, is the enemy.

To be continued