The following is an edited version of a presentation recently delivered by WSWS arts editor David Walsh in New York City and the Detroit area.

When one considers the state of filmmaking, and art in general, one’s first response is, or ought to be, in my view, a profound sense of dissatisfaction. The spectator, or reader, or viewer, currently experiences a troubling lack of depth, texture, and social and psychological complexity. In short, there is an absence of the world, largely.

Certainly the world that great numbers of people know and experience on a daily basis: the world of work, or lack of work, the vast and complicated series of everyday social relationships, the startling changes in life in recent decades, the enormous inequalities and iniquities, the slipping into the social abyss of so many, the struggle to keep one’s head above water that characterizes the lives of tens of millions in this country, billions worldwide… and the emotional conditions, the drama, tragedy andcomedy associated with all that.

Telling the truth is difficult, as George Eliot and Tolstoy both noted, but contemporary art and film, in our view, are failing badly in telling important truths, the truths that are vital to people.

No doubt there is a great deal of ideological and political, and even moral, confusion in this country—we aren’t mesmerized by that and struggle to overcome it on a daily basis—but one must say that the failure of film and novels and plays, in the first place, to hold up a mirror to the country adequately in recent decades, to expose American society’s crimes and injustices, to show the population its own shortcomings, is a factor in the confusion.

We’ve made the point before: the Russian novelists of the 19th century, by their combined efforts, contributed to the discrediting of official society and its eventual downfall. What should we say in this regard, by and large, about contemporary American filmmakers and writers? Have they exerted themselves, made enormous sacrifices in the struggle to clarify and demystify reality, the nature of American society itself? Have they helped the population understand its predicament? The answer is obvious, I think.

Representing the world more fully and richly is not a matter of mere surface details, or of passive recording. When we speak about “the presence of the world” in art, we mean its real presence, which includes centrally its social and historical character. As the Austrian novelist Robert Musil (The Man Without Qualities) commented, creative effort involves not mere description, but an interpretation of life.

At present we lack serious artistic interpretation influenced by the most advanced understanding of reality. The emergence of modern art and culture was inextricably bound up with the growth of Marxism and the socialist workers movement. The decline in the influence of genuine Marxism—not academic leftism, postmodernism, the Frankfurt School, and so forth—has had a serious, harmful impact on art and culture.

A seriousness about showing life in art needs to be revived, for the sake of society and for the sake of art, and that requires the re-emergence of a consciously socialist current in art and filmmaking. That is one of the central themes of this talk. We argue that only the active presence of a critique that takes society down to its bones and holds out an alternative can encourage artwork prepared to tell the whole truth.

Film remains a powerful medium. Some 1.5 billion movie tickets were sold in North America last year, representing about a third of the global total.

However, changing what needs to be changed, I believe much of this discussion applies to fiction and theater relatively directly, and to the other art forms more indirectly—no medium has truly blossomed, except in the formal or technological sense, in the recent period, in my view.

We are confronted with filmmaking’s shortcomings as an artistic and social fact. In terms of mainstream movies, for example, one only has to turn to the mostly dreadful list of Academy Award nominations for Best Picture this year. Up in the Air has possibilities, about a man who lives without relationships and accumulates air miles instead, but it is weakly worked out, in the end. There is Quentin Tarantino’s exercise in historical falsification and sadism, Inglourious Basterds, “fighting fascism with fascism,” as we noted on the WSWS. And Avatar, directed by James Cameron, which offers fascinating technology and little else.

There are several intelligent performances that received nominations—Colin Firth in A Single Man, Anna Kendrick for Up in the Air, and a number of others—but, in general, the nominations are a miserable showing.

And this in 2010! What have we lived through in the first ten years of the new century?

The US media widely acknowledges that the first decade of the 21st century was a disastrous one for American society. Time magazine’s headline read, “Goodbye (at Last) to the Decade from Hell.”

In brief: a hijacked national election, or perhaps two, a major terrorist attack, two criminal wars, vast Wall Street plundering and a massive crash. To what extent, directly or indirectly, have these developments found expression in movies which tens of millions of people affected by these events go to see? Is there a film or are there films that sum up the 2000s in a conscious and meaningful fashion? I’m open to suggestion, but I can’t think of one.

In fact, what sort of a picture of the world could you assemble from the various images generated by most Hollywood films of the past 10 years? Reality as seen through a narrow prism, of people without financial cares, obsessed with trivial concerns; these are dull films by and large, with the great drama of life missing (and the life of the upper-middle-class has not been seriously depicted either, for that matter).

American filmmaking has been able in the past to think more critically, to grasp the whole, or important portions of it—consider these films from the mid 1930s to the early 1940s, just a few of the many extraordinary works made at the time:

These are arguably the three greatest figures in the American cinema, Chaplin, Ford and Welles. All, at the time, considered to be figures of the Left.

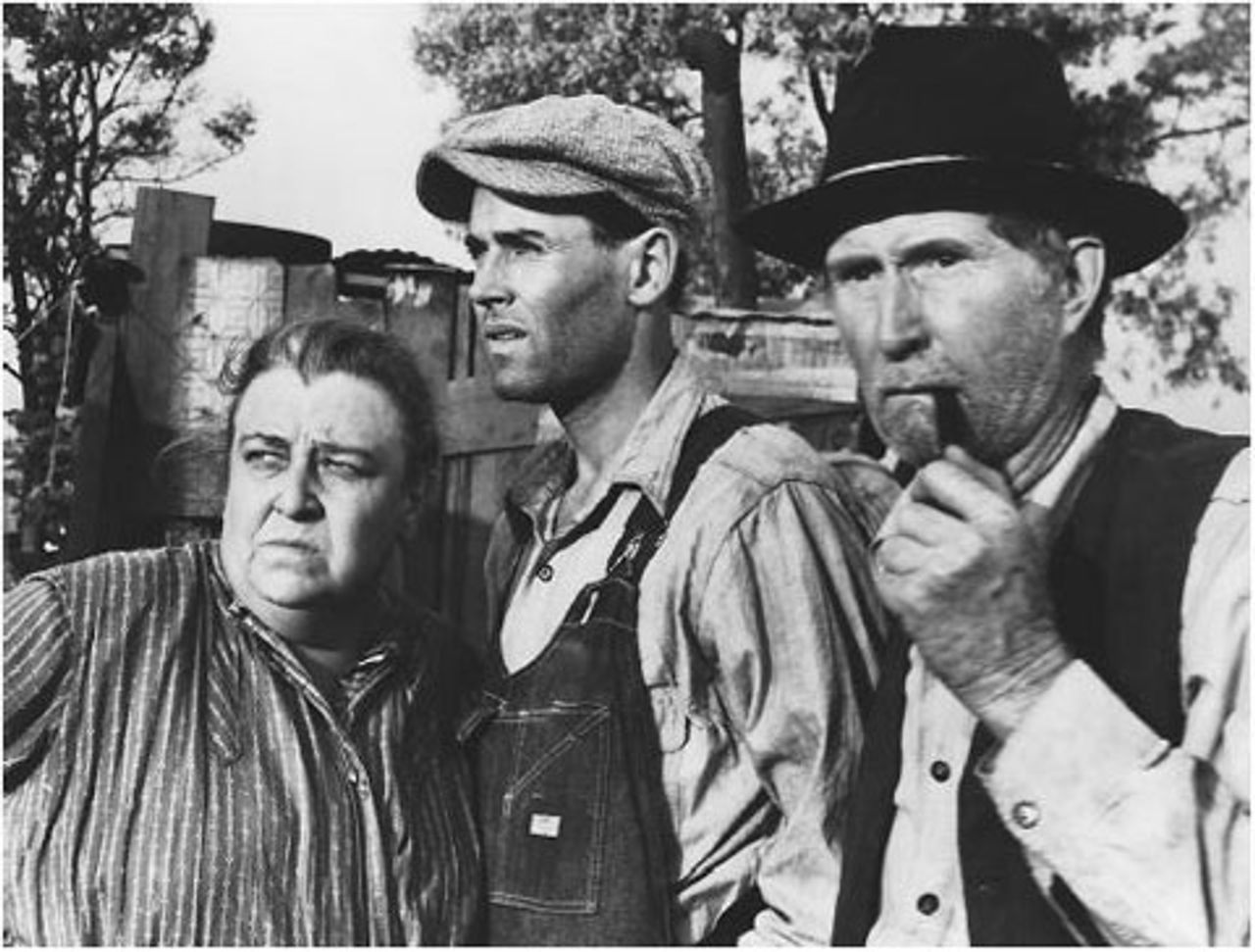

The FBI viewed John Ford as some sort of a subversive. The Informer is a magnificent study of treachery in the political struggle, with an atmosphere worthy of Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz. Grapes of Wrath, despite its occasional sentimental streak, conveys tremendous sympathy for the characters’ plight. This story of suffering and resistance in the Depression made Henry Fonda himself a deeply beloved figure. Is there any equivalent today?

The Informer

The InformerOr is there anything resembling Chaplin’s persona? Or are there personalities as profoundly worked out, as passionately portrayed as Welles’s Kane?

Where is the writer or director or actor today who has become identified with the plight of wide layers of the population?

We don’t feel a trace of nostalgia. There is no golden age we’re seeking to recreate—but there were periods in American filmmaking and individual works that were seen as offering a deep, universal insight into social life. Do we have that today? Or anything near it? Again, the question, I think, answers itself.

Also, it must be said, audiences were more knowledgeable and demanded more. We have to be frank about this: too many mediocre or worse films receive a free pass. American audiences at this point, sadly, ask for and expect far too little. It’s certainly not the fault of the individual spectators, but it remains a problem. We receive email: you don’t like anything, you’re too critical, you shouldn’t expect so much …

We don’t agree. Of course, we make mistakes—one might overvalue a certain work, and undervalue another. However, if we are critical in our appraisals, it’s not our fault there are so many poor and inadequate works, to speak more plainly, so much rubbish. To tell the truth about the problems in a sharp fashion is part of the process of changing things. The population, along with economic and political resistance, needs to build up its powers of cultural resistance.

I would suggest some of the same general difficulties hold true in fiction, drama. Consider this:

Where are the comparable figures and novels? Where are the strong and telling images, the unforgettable characters? The authors, especially Dreiser and Fitzgerald, attempted to make broad, universal statements about American life. Where is the sense conveyed today of a historical period and of important popular moods, reality caught at a very high level, in fact, at the highest level?

F. Scott Fitzgerald

F. Scott FitzgeraldIf we turn for a moment to some of the films of the 1930s and early 1940s. This is not an exhaustive list, or a scholarly undertaking, but a sample of memorable works.

A good number of the movies come from Warner Bros., several are directed by Michael Curtiz, later joined by Raoul Walsh. Warners had James Cagney, Edward G. Robinson, Paul Muni. The films, many of whose very titles are suggestive, are characterized by lively, fierce and snappy dialogue, unsentimentality, realism of a sort—they offer a feeling of the decade. One could learn something about the country, the times, the population, by watching these films.

Bette Davis and Edward G. Robinson in Kid Galahad

Bette Davis and Edward G. Robinson in Kid GalahadThere are also films on the list by German émigré Fritz Lang and John Huston. Lang’s You Only Live Once and Fury—the latter about a lynching—arefrightening films about injustice.

High Sierra

High SierraHigh Sierra, with Humphrey Bogart and Ida Lupino, one of the most expressive performers of the era, is a particular favorite. It conveys a definite sense of the Depression years, their harshness, including their psychic harshness, but also enormous tenderness and sensitivity that somehow survive, like flowers growing through cracks in rock.

Casablanca, Maltese Falcon, of course, are well-known films.

In the end, these movies and others can only be accounted for by the fact that Hollywood had a large left wing and also a politically aware European émigré constituency in the 1930s and 1940s. The Depression, the rise of fascism, and the example of the Russian Revolution had an enormous impact on the film community. It is a very contradictory phenomenon, with many tragic aspects, because of the role of the Stalinist Communist Party, but it remains a fact that when the anti-communist purges came, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the authorities had to drive out, discredit or intimidate hundreds and hundreds of writers, directors, and actors.

The list of left-wingers in Hollywood included, as one work on the subject notes, “Lucille Ball, Katharine Hepburn, Olivia de Havilland, Rita Hayworth, Humphrey Bogart, Danny Kaye, Fredric March, Bette Davis, Lloyd Bridges, John Garfield, Anne Revere, Larry Parks, some of Hollywood’s highest-paid writers, and for that matter the wives of March and Gene Kelly along with Gregory Peck’s fiancée.” (Radical Hollywood: The Untold Story Behind America's Favorite Movies, Paul Buhle and Dave Wagner) Also, Franchot Tone—then married to Joan Crawford—Jose Ferrer and apparently Ronald Reagan, all of whom were in or around the Communist Party periphery.

As I noted a few years ago: “One could add Sterling Hayden, who turned informer later on, then regretted it, Sylvia Sidney, Shelley Winters, Lauren Bacall, and many, many others. Melvyn Douglas and Frank Sinatra were also named by an FBI informant, along with Paul Muni, born in Ukraine and a veteran of Yiddish theater in New York, whose career was wrecked by the blacklist.” John Ford, as I mentioned, was under suspicion at one point, and Chaplin and Welles were effectively driven out of the country.

The influence of the émigrés—many of whom had been raised in major cities, and were exposed to European culture and politics, in which the socialist labor movement played a central role—was a factor in giving Hollywood films a more sophisticated content in the 1930s and 1940s.

We observed as long ago as 1996, in the International Workers Bulletin:

Let’s consider this list of postwar films:

A film such as William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives, about returning World War II veterans and their discontents, dealt with experiences through which masses of people passed, the experiences of a generation. The title is ironic. The film takes an “unpatriotic,” realistic view of things. It is critical of the treatment of war veterans.

Or one could point to John Ford’s wartime film They Were Expendable (1945). The title refers to the US Navy’s attitude toward PT boats and their crews. Would anyone in mainstream Hollywood dare today to make a work critical of the military?

It is worth mentioning as well other wartime films such as Howard Hawks’s To Have and Have Not and Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (both from 1944), the latter a savage film about American lower-middle-class mores.

Or take some of the leading actors of the period. Simplification, caricature and emotional ‘rounding off’ were very much present, but, at their best, performers embodied something about the American personality, or personalities.

Take Edward G. Robinson and John Garfield, Jewish working class types, or working class intellectuals. Robinson, who met with Trotsky in Mexico, Garfield, a supporter of the Communist Party, essentially hounded to his death. James Cagney, born in the tough Yorkville section of Manhattan, anti-clerical and left-wing, at least until the authorities got to him.

Or Bogart, who grew out of the gangster parts in the late 1930s into something interesting in films such as High Sierra, Maltese Falcon, Casablanca, To Have and Have Not, Key Largo and others. In Casablanca and To Have and Have Not, in particular, he plays the pragmatic, efficient individualist, who initially rejects a political or social appeal, but, in the end, responds strongly to the plight of the oppressed, proves capable of solidarity and of democratic sensibilities.

Women’s roles expanded, and became more interesting, an important indicator of the relatively democratic, popular character of the films and filmmaking. A Barbara Stanwyck, for example, and numerous other tough working class or lower-middle-class girls, women—Joan Crawford, Jean Harlow, Ginger Rogers (aside from her dancing pictures): prepared to go to nearly any lengths to survive. The pre-Production Code films are even more explicit. Stanwyck, the former Ruby Stevens from Flatbush in Brooklyn, who worked as a wrapper in a department store…

Women who are intelligent, quick-witted, no pushovers, like the population itself: Bette Davis, Carole Lombard, Mary Astor, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, etc. In the 1940s, Lana Turner, Gene Tierney, Lauren Bacall, Joan Bennett, Veronica Lake, Ann Sheridan, and many others.

Compare these personalities to the present state of things. There’s a George Clooney, for example, a talented performer. His characters are clever, but don’t take themselves too seriously, ready to improvise and roll with the punches, if necessary. Capable of showing a darker, tougher side. But his persona is far less defined so far, in social terms. Among female performers, there are even fewer figures who have been given the opportunity to represent something substantial. There are enormously talented actors, that’s not the issue at all.

Grapes of Wrath

Grapes of WrathThe opposite today of a Henry Fonda—in You Only Live Once, Young Mr. Lincoln and Grapes of Wrath—might be the unfortunate Tom Hanks. Considerable effort has been made to turn him into an “American Everyman,” in Saving Private Ryan and elsewhere. In Forrest Gump, a terrible film, he was meant to represent that Everyman as an idiot. Hanks has lent himself to efforts intended to strengthen myths about America, about the Second World War, about the “Greatest Generation,” and all that. None of that, however, has won him spontaneous public affection.

Numerous titles on that list of postwar films are suggestive of nightmares and delirium, ‘whirlpool,’ ‘caught,’ evil, nighttime, haunted… Several factors come into play—in the first place, the horrors of the Second World War and the Holocaust. But, as time passes, by 1948, let’s say, there is also the pressing matter of the reality of postwar America, which is revealing itself. One thinks of such films as Lady from Shanghai, Key Largo, Force of Evil, for example. An important new theme emerges: the powerful presence in postwar society of profiteers and criminals, including criminals in business suits.

Contrary to the illusions spread by the Communist Party and its periphery, the postwar did not mean the expansion of the New Deal, a flowering of democracy. This conception was bound up with entirely false conception of the war itself, which was not a war for democracy, although millions went to fight fascism, but a war between great power blocs, an imperialist war. The Stalinists ignored the brutality of the Allied bombings of German cities, applauded the incineration of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They and those around them were utterly unprepared for the Cold War, the anticommunist witch-hunt and the purges, with disastrous consequences.

If one turns to the films of the 1950s and 1960s:

Indeed, in the 1950s certain ‘classical directors,’ Hitchcock, Ford, Hawks and Raoul Walsh, along with Anthony Mann and others, did some of their best work. And there were new voices, such as Douglas Sirk and Robert Aldrich. The films later in the decade, referred to in the slide, indicate a degree of disappointment, disillusionment with the promise of postwar America. Also, of course, with the collapse of the blacklist and the dissipation of the worst anticommunist hysteria, certain things could now be said.

The 1960s witnessed the collapse of studio filmmaking and the emergence of independents, some of whom are or become identified with the radical wave of the latter part of the decade and the early 1970s.

The early part of the 1970s, connected to the anti-establishment mood among masses of youth in particular, produced some films that ‘got’ certain situations and realities, that still attempted to make wide-ranging comments about American life. Of course, one thinks of Roman Polanski’s Chinatown. The Polish émigré helped create a scathing indictment of American big business and politics. Francis Ford Coppola gave us The Godfather, which argued that in America crime is business and business crime.

The most interesting group of films, in my view, may be Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller, California Split, The Long Goodbye, Thieves Like Us and Nashville. The latter, even if it is confused, makes an effort to link politics, celebrity and business in America.

Later in the decade there is Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, which, despite its occasional absurdities, is a remarkable film, expressing something of the horror and revulsion of a generation against the crimes committed in Vietnam by American imperialism. As we commented when it was re-released in 2001, an atmosphere of menace prevails throughout. We wrote, “One has an uneasy feeling that every time a group of Americans forms, violence will erupt.” Coppola’s ambitious film is an indictment of colonialism and its catastrophic consequences.

It seems worth noting, however, that the socially critical films of the 1970s, as valuable as some of them were and remain, generally lacked something present in earlier left-wing American filmmaking, with all its contradictions: a substantial interest in and the presence of the working class, or wide layers of the population, and their lives and problems in general. There is also a noticeable lack of interest in the great historical events of the 20th century. These limitations speak to the nature of the radicalization of the time and all the complex questions it left untouched.

In the 1970s too, Mel Brooks and Woody Allen made some of their best films. Sidney Lumet as well. Hal Ashby, Terrence Malick and Michael Cimino arrived with interesting, if flawed, works.

In the 1980s, in the face of the Reagan administration’s attacks on the population, carried out with the collaboration of the Democrats, and a sharp turn to the right in the American elite, the films that stand out are those that resisted the generally reactionary tide:

Warren Beatty’s Reds, about John Reed and the Russian Revolution, Woody Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanors, on the ruthless selfishness of New York’s upper-middle class, Barry Levinson’s Rain Man, a criticism of the prevailing worship of greed, Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate, a view of bitter class struggle in the 1890s in Wyoming, Oliver Stone’s Wall Street, about the criminal element rising to the top in American financial circles. Stone, to his credit, also made important films about the Vietnam War, Platoon and Born on the Fourth of July. Later in the decade, Michael Moore made his first feature, Roger & Me, about the decline and fall of Flint, Michigan.

Reds

RedsThere were numerous serious or well-intentioned efforts, including Edward Zwick’s Glory and John Sayles’s Matewan, but one must say: given the character of the assault on the population begun by Carter and undertaken vigorously by Reagan and the first Bush, the cinematic and artistic response overall was very weak and limited. By and large, the population was not clarified, whereas in Britain, in the work of Mike Leigh, Ken Loach, Stephen Frears and numerous others, there was a more concerted and conscious response to Thatcher, although one would not want to idealize the situation there either.

Things only got worse in American filmmaking over the next two decades, the 1990s and 2000s. These are some of the more interesting films. I don’t vouch for every title on these lists, and, in fact, we criticized some of them quite sharply when they first appeared.

This is not a wasteland, and there are some lively works. In 1995 (The Underneath, Palookaville, Welcome to the Dollhouse, To Die For, and Safe) and in 1998-1999 (Buffalo 66, Bulworth, The Newton Boys, Pecker, The Truman Show, A Simple Plan, The Thin Red Line, The Insider, Election, Rushmore, Boys Don't Cry) in particular, for some reason. There are also the last interesting movies by Woody Allen, Richard Linklater’s films, Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List and Robert Redford’s Quiz Show.

To Die For

To Die ForI do like Gus Van Sant’s To Die For, which perhaps has Nicole Kidman’s best performance. She plays a young woman obsessed with fame and celebrity to the point of organizing the murder of her husband. As the narrator explains: “Suzanne used to say that you're not really anybody in America…unless you're on TV. ’Cause what’s the point of doing anything worthwhile...if there’s nobody watching?”

The decade produced a number of insightful works, but, interestingly, very few have been followed up on by the various writers and directors.

The World Socialist Web Site was launched in February 1998, and one of the first cultural issues we confronted was the immense success of Titanic.

(I would say the same on the whole about James Cameron’s Avatar, incidentally, although it does have some powerfully anti-militaristic imagery.)

We received hundreds of letters about Titanic, most of them protesting our view, but a discussion was initiated that has never stopped. Cultural criticism, film criticism in particular, is not an exact science. We have made mistakes, we have overvalued some films, undervalued others, but I think the general trend of our analysis has been vindicated.

I’d like to cite a few excerpts from film reviews or comments that referred to various social and cultural processes.

In A Simple Plan (1999), three people find $4 million in the cockpit of a crashed airplane, and eventually, of course, fall out, with tragic consequences. The movie, directed by Sam Raimi, better known these days for the relatively empty-headed Spiderman films, is set in the middle of nowhere, in the middle of winter. There is a general sense of straitened circumstances and narrowing prospects, the abandonment of the population by all official institutions, and the weakening of old allegiances.

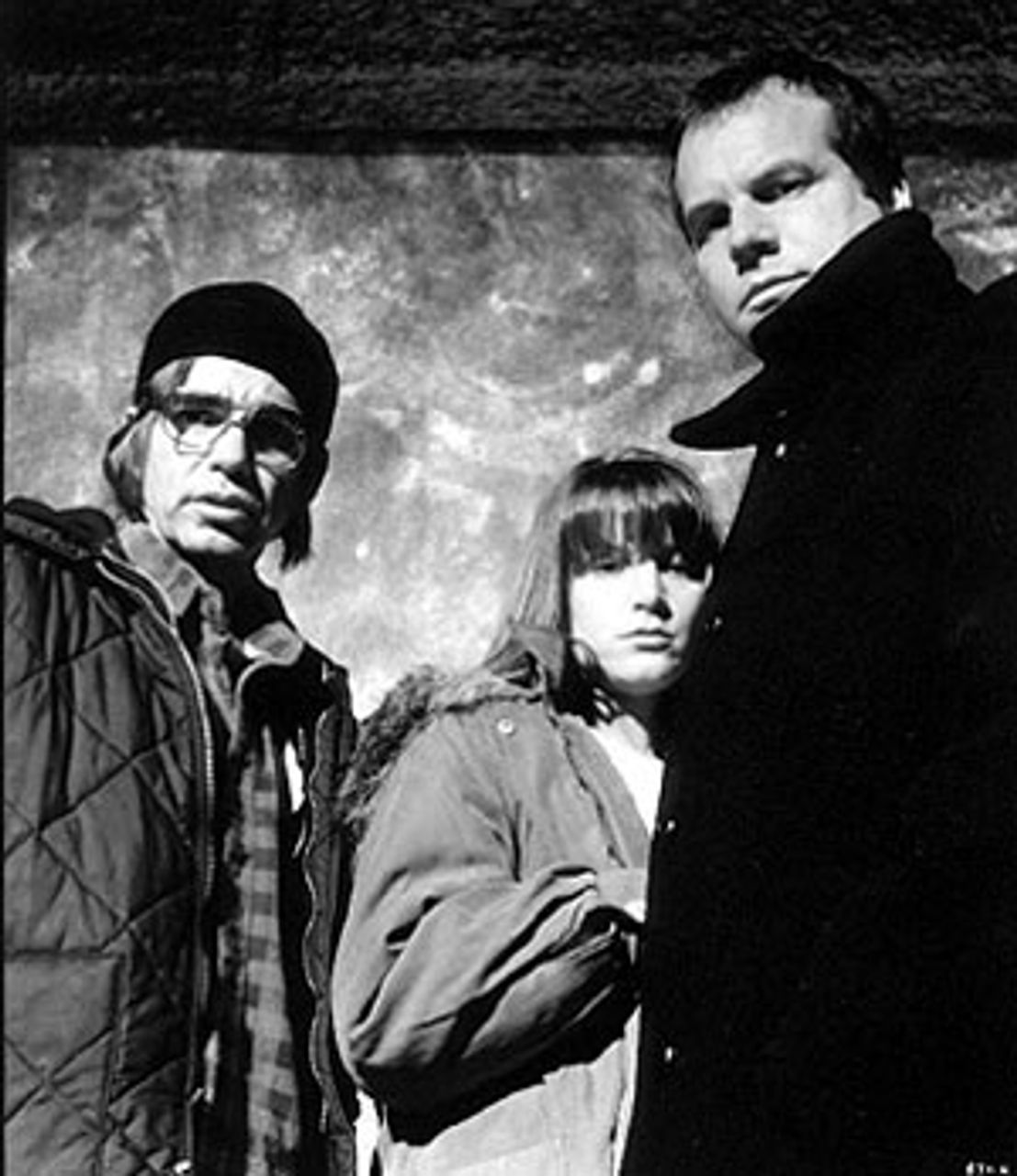

A Simple Plan

A Simple PlanIt is a considerably more volatile and unstable mix 11 years later, as the recent episode in Austin, Texas, where an angry software engineer flew his plane into the local offices of the Internal Revenue Service, only underscores.

Kimberly Peirce’s Boys Don’t Cry (also 1999) dealt with the horrific murder of Teena Brandon, who attempted to pass as a boy, in Nebraska. More than anything else, however, the film gave you a glimpse of life in small-town America, poor, isolated, desolate as hell.

This was a generally weak decade. I’ve highlighted a greater number of films, which reflects the relative closeness with which the WSWS follows the cinema, but, in fact, I would argue that the last two decades were probably the poorest for the medium since it was invented in 1895, or at least since the 1910s.

There are the last films of Robert Altman in the 2000s, the films of Wes Anderson, the Coen brothers, Michael Moore, Alexander Payne.… I thought Wim Wenders’s Land of Plenty was one of the most moving and complicated films about the American social situation and mood. Michelle Williams also appeared in Wendy & Lucy, which, along with Frozen River, indicated a deeper social interest and concern on the part of filmmakers—still very much a rare occurrence.

We noted a tendency, which I referred to previously: the inability of many filmmakers to follow up, mature, deepen initially interesting, even provocative work. One had to ask: why did the filmmakers find it so difficult to develop? Were they working from too narrow an intellectual, artistic basis?

At the same time, we witnessed the emergence of genuinely anti-social, malevolent trends: Quentin Tarantino and his imitators, from the mid-1990s onward. Indeed, we continue to see the flourishing of this sort of thing, in the raft of porno-sadistic horror films, and Tarantino’s films themselves.

This is what we said about his Kill Bill, Vol. 2, in 2004:

A number of interesting films came out in 2005, including Syriana, Munich, Good Night, and Good Luck, Gunner Palace (the documentary about the Iraq war), The New World and Brokeback Mountain.

Munich

MunichAbout Munich, we commented:

Clearly, the films in mid-decade were associated with a growing horror over the Iraq war, the Bush administration and its open criminality, militarism and brutality, its contempt for democratic rights, its use of torture and secret prisons.

At the same time, we pointed to the real limitations of Hollywood’s “new seriousness,” that the filmmakers had far to go, and I think that warning has been confirmed. (The election of Barack Obama, in particular, has apparently occasioned a serious—and revealing—weakening of the critical faculties.)

If we turn to the films directly on the subject of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars (or that are intended to refer to them), or the Bush administration, we can see some of the problems. This is not an exhaustive list either, obviously, but it is representative, I think:

There are numerous pointed works here (In the Valley of Elah, Rendition, The Situation; and Death of a President and Battle for Haditha, which were made by British directors), as well as some generally lamentable ones (Charlie Wilson’s War, Lions for Lambs, W., The Hurt Locker.…). Also, the documentaries by the team of Michael Tucker and Petra Epperlein, and James Longley’s Iraq in Fragments.

Numerous pointed films…but if one may say it, these are primarily “small-bore” works, works that take up elements, specific aspects of the situation. If one compares them, as a body, with Apocalypse Now, or even Platoon, for all its histrionics—the latter were movies that attempted to make a broad statement about American involvement in Vietnam, to paint it as a crime, as an imperialist crime. This element is largely missing today.

The “non-political” war film finds its apotheosis in The Hurt Locker, whose claim to fame is its “neutral” stance in relation to the conflict itself. It’s no such thing. Director Kathryn Bigelow admits to being fascinated, mesmerized, by war and violence, and the film ends up glamorizing a new (or fantasized) kind of American hero. We called it part of a “deplorable trend” in our review last year, and we stand by that.

If we consider the films of the 1990s and 2000s as a whole, what overall picture could we draw? That a good number of colorful, lively, innovative and clever works were released, containing, in some cases, extraordinary moments. Today’s films, and the better television programs (HBO series, even certain network situation comedies), contain many attractive features, including remarkable individual characterizations and recreations of specific social circumstances, and, on occasion, the representation of historical events that are spot on.

Numerous intriguing films and series, but none of them attempted to trace problems to the social order itself, none of them traced social and historical evolution. There is almost no universal critique. Again, these are essentially small pieces, small-bore. We have witnessed a tremendous weakening of the ability to confront society as a whole.

I want to point once more to the events of the last decade or so. Because we’ve lived through it, because it is already our past, there is something of a tendency to take for granted, to accept as inevitable, what has happened to and in American society.

But consider for a second what the population has experienced: a manipulated sex scandal and a near coup d’état in the late 1990s; the hijacking of a national election (or two) essentially unopposed by the liberal establishment; a massive terrorist attack that has never properly been investigated or explained to the American people; a neo-colonial war in Afghanistan now expanding to Pakistan; the invasion and occupation of Iraq justified by shameless lies, with the full collaboration of the media and both parties; endless threats against Iran and other regimes that are perceived to stand in the way of the US; the locking up of suspects in secret prisons and torture sites; a sustained attack on long-standing constitutional rights; the illegal doctrine of pre-emptive war; the massive corporate looting of the economy, to the tune of trillions of dollars; a devastating crash and subsequent bailout of the banks, also to the tune of trillions of dollars; the growth of immense social inequality and social misery in the US, with tens of millions of people unemployed or underemployed; major cities ravaged (the city of Detroit is suffering from a 50 percent unemployment-underemployment rate).…

All this—and virtually none of it has been treated seriously in films (or novels or drama). From the point of view of formal logic, it’s almost incomprehensible. As though you were a photojournalist standing at the window with a camera in your hand, an extraordinary uproar erupted in the street, and you deliberately turned away and took pictures instead of your children doing their homework. Some considerable countervailing pressure must be at work.

These are unprecedented events. They haven’t gone entirely unnoticed or uncritiqued, but, one must say, in relation to the depth of the transformations, the artistic response has been entirely inadequate, statistically almost insignificant.

The power of money, extensive corporate control, and direct political pressure certainly play a role. However, there are also nominally independent film festivals. Individuals with video cameras and editing equipment can create their own works. There is very little of significance in this sphere, either. The only benefit of American “independent” cinema at the moment is that by and large it makes you long for Hollywood’s products. I don’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings, but we are confronted for the most part with the self-involved, unenlightening products of 28- and 30-year-olds who have very little to say.

In our view, the artists have proven ill-equipped, unprepared intellectually for the developments.

The ideological pressures following upon the collapse of the Soviet Union and the other Stalinist regimes in 1989-1991, all the blather about “the end of socialism,” “the end of history,” as well as the decay of the old labor movements in every country, and the social conditions that have emerged for masses of people bound up with these problems—all this has had consequences.

The reactionary climate of the past several decades in general has had an impact. The enrichment of sections of the upper middle class and their lurch to the right are facts of American social and political life. There has been a fantastic accumulation of wealth by a relative handful, including in the entertainment industry.

This is a very conspicuous process in New York City. Woody Allen and others have either made that same transition or succumbed, or been laid low, by its pressure.

That is part of the explanation, but it begs the question: why were the intellectuals so unprepared for those processes, why were they so vulnerable?

A fundamental theme of this presentation is the need for a consciously socialist current in filmmaking and among artists in general. We’re not speaking of some sort of political litmus test, in other words, encouraging the emergence of artists who would win our ideological approval for some sort of short-term gain. That’s not the issue at all. This is a practical, artistic and social necessity. We are inundated with films, novels and plays that go so far…and no farther.

We have lived for decades in this country under conditions produced in part by official anticommunism, McCarthyism, the purges of left-wing forces from the unions, from film and television. Socialist thought was criminalized, marginalized, excluded. This is a central element in our current difficulties. And, it must be said, the radicalization of the 1960s did not make deep inroads here.

But art despises half-measures. It is untenable in the long run: making a half-critique, pointing to this or that surface development, this or that symptom.

Where is the artist today at total war with official society? Where is the artist who says: “I despise all this, patriotism, nationalism, war, the military, religion, the government, parliament, business, profits”? Who says, “I hate the hypocrisy, the criminality, the greed of the ruling classes. I want nothing to do with such people, I’ll search out and align myself with their enemies.” Artists have said and done this in the past, modern art is inconceivable without it.

The crimes of Stalinism threw an entire generation, or several generations, into crisis, from the mid-1930s onward. The terrible deeds carried out in the name of communism brought discredit on the noblest ideas in history. Stalinism itself, its twists and turns, its cynicism, its catastrophic policies, demoralized artists and intellectuals in the late 1930s and 1940s. Its crimes were then used by the witch-hunters and their liberal allies to justify the purges and the blacklist.

The artists are suffering from the combined effects of the traumatic events of the twentieth century. But these events and their consequences need to be studied, understood and overcome. Serious progress is impossible without that. It is simply not possible, in the first place, to represent truthfully the character of contemporary relations between people on this planet unless you understand the history of those relations as social phenomena.

What’s needed? A number of things, in our view.

Greater artistry and intellectual effort. Art is exhausting, unsettling, difficult work. We have referred numerous times to the film school graduate with the unfurrowed brow. There is the problem of what the younger generation of filmmakers has been through, seen, experienced.

The 20-year-old film student wasn’t born at the time of the last major successful strike struggle in the US, when the working class made itself powerfully felt, the miners’ strike of 1977-1978. He or she would have been born around the time of the demise of the Soviet Union.

The 30-year-old artist was born around the time of the miners’ strike and would have been 10 or so in 1991, when the USSR collapsed. In reality, you would have to be 35 or 40 years old simply to have experienced mass struggles in this country, or the existence of something officially supposed to represent an alternative to free market capitalism.

People can’t be blamed for what they haven’t lived through, but we have to tell the truth. We say to the artists: what you know, what is in your head, is inadequate. You have to be oriented toward bigger questions, questions of society and history first and foremost. That doesn’t have to be the substance of your work, it doesn’t matter how intimate your immediate subject might be, another War and Peace or a love lyric, but there remains the need for the broadest thought and understanding, for presenting complex and difficult problems, all of which require real intellectual struggles.

Texture, complexity, and depth come with knowledge, deep emotion, a deep understanding and feeling for the art form itself, its human and artistic possibilities, and not merely its technical capabilities, much less the desire to impress or to show off. Art is about showing life, not having a career.

As I’ve suggested, we need to revive protest, anger, and outrage, the desire to see the world changed from top to bottom. It’s hard to conceive of important work in our day without that. Absolutely critical, in our view: the artists must overcome the prejudice against socialism! Absolutely no major progress will occur without that.

If the artists brought together the technological innovations of the recent period, its freshness and cleverness, its color and rapid movement, and the ability to impart vast amounts of information quickly and clearly, with important ideas, artistic elegance and seriousness, and with a concern for humanity and its fate…that would open the road to important work, in our view.

In 1928, Soviet literary critic Aleksandr Voronsky—Left Oppositionist, co-thinker of Trotsky, and eventual victim of Stalin in 1937—addressed this problem. It was part of his struggle for more seriousness about life and genuine engagement with the world in Soviet writing. He commented:

I believe this is profoundly important. There is no going back to Ford or Welles. The greatest work, we have confidence, lies ahead. But the ingenuity of present-day filmmaking has to be combined with far deeper knowledge of the world, to bring out the true character of contemporary life, to enlighten and broaden the population, to appeal to what is best in it, to contribute to the cause of liberating global humanity from ignorance, exploitation and poverty.

A final point: what we have been discussing are objective problems, social problems, historical problems. We are farther than anyone from blaming individuals for the difficulties. We don’t (or we try not to) heap abuse, on the pages of the WSWS, on the artists who fall short, even those who fall very far short. The problem lies outside them, in historical traumas and difficulties that have yet to be overcome, in new realities that have yet to be cognized. We fight with great urgency for a different perspective, a different orientation, but we also understand that big popular movements will play a critical role in dispersing the “clouds of skepticism and pessimism” (Trotsky).

As the working class begins to move, and it will, many of today’s problems will seem trivial, or will disappear entirely. A new set of challenges and problems will arise, and we certainly welcome those. We will do everything in our power to assist the artists, the filmmakers, to arrive at a deeper understanding of the historical and social issues involved.