William Shakespeare

William ShakespeareA reader, HS, has written to us complaining that the review of Anonymous, the film by director Roland Emmerich and screenwriter John Orloff, was an “emotional rant” that did nothing more than “parrot the shop-worn clichés of the multibillion dollar Shakespeare establishment.” [See letter.]

In regard to the last point, it feels a bit like coming under attack for parroting the shop-worn clichés of the multibillion dollar Copernicus establishment who continue to insist, despite persuasive evidence, that the earth is not at the center of the universe …

HS argues that the review made “personal attacks” on Roland Emmerich. It did no such thing. It responded to his films and public comments. The German-born Emmerich has distinguished himself by a series of crude and bombastic films (Godzilla, Independence Day, The Patriot, etc.).

We are furthermore informed that Emmerich is “one of the most prominent gay directors in the world” (by which HS means, presumably, one of the most successful commercially), to which we reply: frankly, we could not care less.

In any event, the phrase “gay director” is useless from any meaningful sociological or artistic point of view. As a piece of biographical information, a given individual’s sexual orientation may be of some significance and interest. As an artistic identification or qualification, it is absurd and beside the point.

There are thoughtful and insightful directors who happen to be gay. There are also, one need hardly add, vulgar and superficial filmmakers with the same sexual orientation. In our opinion, Emmerich falls into the second category. Watching Anonymous is a painful experience, aside from (although bound up with) its central historical argument.

HS argues (twice!) that Anonymous’ purpose is “to set the record straight” by identifying the true author of Shakespeare’s works, the 17th Earl of Oxford, Edward de Vere. Our letter writer interprets the phrase “setting the record straight” in a generous, one might almost say, luxuriant, manner.

To list the inaccuracies, absurdities and unproven (and groundless) speculations in the Emmerich-Orloff film would take up more space than the effort would be worth. We will refer to a few, some of which were mentioned in the original review and ignored by HS in his email. (We hope our correspondent will not chide us, like Scott’s comical Sir Arthur Wardour, for a tendency to avail ourselves “of a sort of pettifogging intimacy with dates, names, and trifling matters of fact.”):

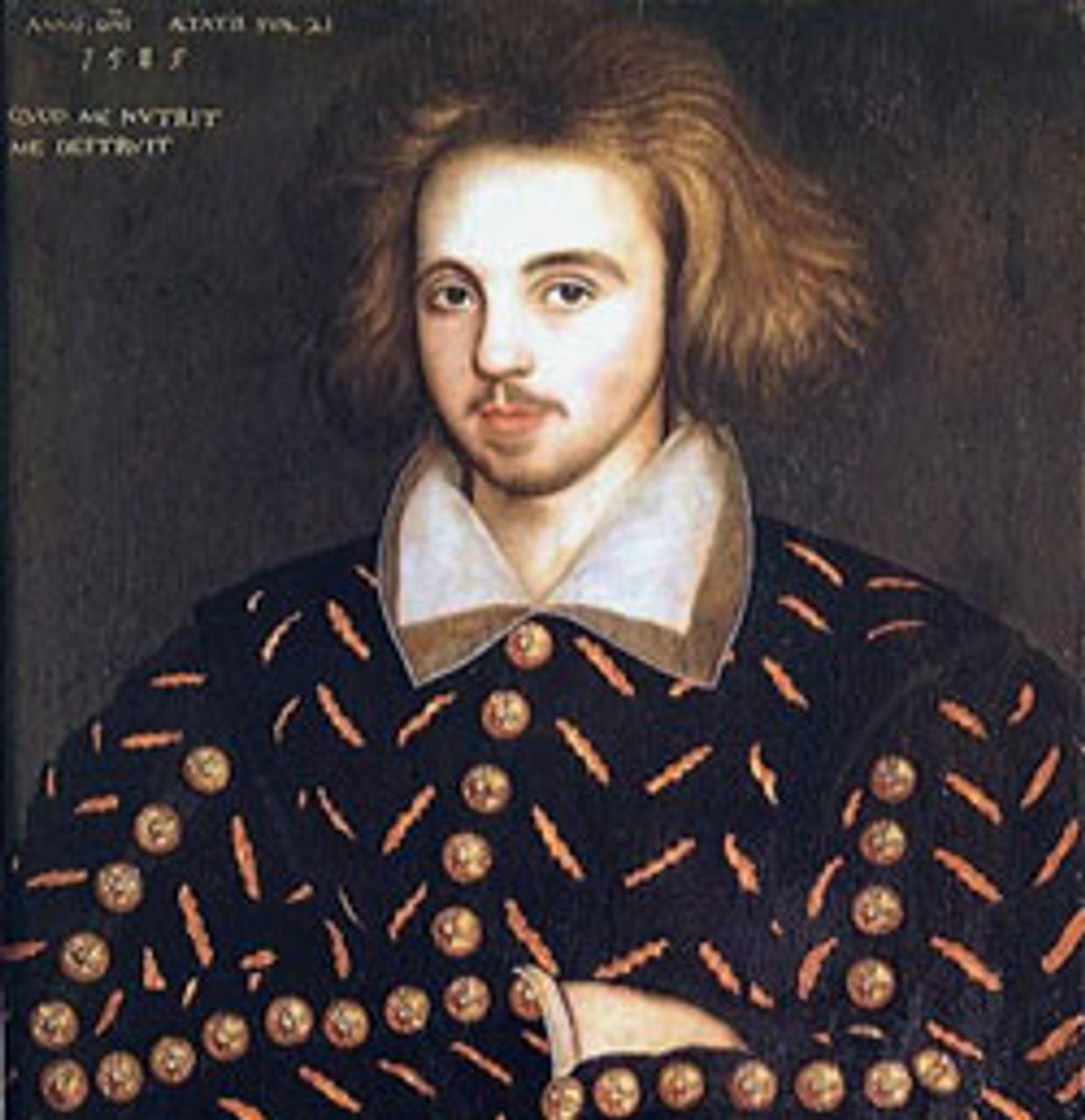

Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe*The dramatically important presence in Anonymous of a sinister (and grotesquely misrepresented) Christopher Marlowe in c. 1598, when Marlowe had been killed in 1593. Marlowe ridicules a play not written until five or six years after his death.

*The rather hilarious contention that the aristocratic Earl of Oxford wrote A Midsummer Night’s Dream, in which plebeian elements play so prominent a role, at the age of nine or so, in 1559.

*The writing and staging of Richard III to assist the Earl of Essex in his 1601 insurrection, when a printed text of the play exists from 1597 and a second edition appeared in 1598. The play that coincided with Essex’s rebellion was actually Richard II, which does not include a hunchbacked villain.

*The claim that Elizabeth I had numerous illegitimate offspring (the number not specified; at least three, according to the film), with one of whom (the very Earl of Oxford) she also had an affair and by whom she had one of the aforementioned offspring (the Earl of Southampton).

*The assertion that Shakespeare’s playwright contemporaries would have been astounded by the fact that Romeo and Juliet was “A romantic tragedy [written entirely] in iambic pentameter” (which it is not, in fact). Professor Holger Syme of the University of Toronto points out that numerous English dramatists, including Marlowe and Thomas Dekker (another character/victim in Anonymous) “wouldn’t have found anything remarkable in a blank verse line, having expertly bombasted them out for years. Never mind that the innovation on stage wasn’t verse, but prose.”

*The presentation of Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis, a poem first published in 1593, as a brand new work written for Elizabeth as a special tribute by her old lover, Oxford, and published in February 1601.

*The depiction of Robert Cecil, a chief advisor to both Elizabeth and her successor, James I (James VI of Scotland), as the avid supporter of James and enemy of Essex, the latter portrayed as the aristocratic-patriotic foe of the Scottish king. James Shapiro points out in the Guardian that “it was Essex who was King James’s most avid supporter in England [and with whom Essex allegedly corresponded during his first imprisonment] during the closing years of Elizabeth’s reign, and William Cecil who feared James bore him a grudge for his role in the death of James’s mother, Mary Queen of Scots.”

*The decision to portray Polonius in Hamlet as a caricature of William Cecil, Robert’s father and predecessor as adviser to Elizabeth, a subversive and satirical attack on a living official instantly recognized by the audience. The only difficulty is, William Cecil had been dead several years by the time Hamlet was first staged, apart from the fact that such a heavy-handed attack would have been historically out of the question.

*The entirely made up and ludicrous persecution and near-torture of playwright Ben Jonson for his supposed part in the Shakespeare-Oxford shenanigans, for which there is no basis whatsoever, except in Orloff’s limited imagination. (Jonson landed in jail several times, once for manslaughter, but never for anything to do with Shakespeare and the Earl of Oxford.)

*The burning down of the Globe Theatre by Robert Cecil’s thugs, ten years before the theater actually was destroyed, in an entirely unrelated manner (a theatrical cannon, set off during a performance of Henry VIII on June 29, 1613 misfired and ignited the wooden beams and thatching).

Is all this mere “poetic license?” Beyond a certain point, quantity turns into quality. Orloff has not merely rearranged a few facts, he has reorganized Elizabethan political and cultural life to suit his schema.

As noted in the original review, Orloff and Emmerich want to have their cake and eat it too. On the one hand, Orloff, for example, states that “I wanted my script to be as factually accurate as possible;” on the other hand, in the same Wall Street Journal article, he argues, “The truth is, there is no truth in film—in any film. Even the films that we think are true, about real people in real places, actually aren’t!” For a classic statement of careless, vaguely “postmodernist” relativism and laziness one could hardly do better.

As for the argument that Shakespeare did not write the plays attributed to him, there are innumerable books and essays that lay out the contrary argument. In regard to the claims that there is no evidence of Shakespeare’s existence or his connection to the plays, and specifically no contemporary references to his work, this web page brings together some of the evidence.

A few points, however.

HS repeats the claim that no letters from Shakespeare exist. In fact, both Venus and Adonis (1593) and The Rape of Lucrece (1594) have introductory epistles, signed William Shakespeare and addressed to the Earl of Southampton. Both letters are written in a fawning style, appropriate for a commoner addressing a nobleman and which would have been unthinkable for an aristocrat such as the Earl of Oxford.

Ben Jonson

Ben JonsonThe First Folio edition of Shakespeare’s plays (1623) contains as a preface the extraordinary and profoundly moving poem by Ben Jonson (a fellow playwright who might have been expected to know what was what) “To the Memory of My Beloved the Author, Mr. William Shakespeare”. Jonson addresses the playwright, his late friend: “Soul of the age! The applause, delight, the wonder of our stage, My Shakespeare, rise!”

The poem contains the line, “Sweet Swan of Avon!” referring to Shakespeare, which ought to settle the argument (Stratford-upon-Avon was Shakespeare’s birthplace, not the Earl of Oxford’s), but the makers of Anonymous and presumably others of the anti-Shakespeare persuasion subscribe to a “theory” as to why Jonson was concealing the real identity of the author. Those who find this convincing are welcome to it.

There are other types of proof. The advocates of Oxford are obliged to claim that the 37 plays were all written before 1604, the year of the Earl’s death, “kept in manuscript, and subsequently revised by the players with topical allusions to post-1604 events added in.” (Jonathan Bate, The Genius of Shakespeare) Why this would have been done, no one can reasonably explain. Professor Bate continues, “But this argument is fatally flawed in the cases of Macbeth and The Tempest: the former does not merely allude to the Gunpowder Plot [of 1605], it is a Gunpowder play through and through, while the latter could only have been written after the publication of Florio’s translation of Montaigne in 1603 and the tempest that drove Sir George Somers’ ship to Bermuda in 1609.”

Aleksandr A. Smirnov

Aleksandr A. SmirnovFurthermore, the analysis made by Soviet critic Aleksandr A. Smirnov of Shakespeare’s later plays, although not directed against the Oxford advocates, is striking. Smirnov, in Shakespeare: A Marxist Interpretation, points to the changes in the London Theater after 1610, which became “very strongly aristocratic in flavor because of the growing royalist patronage and the irreconcilable hatred of the Puritans for the stage.” A different type of play, associated with the influence of the dramatist collaborators Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher became the vogue.

Shakespeare was crowded off the stage, and responded, Smirnov argues, by making “certain ideological concessions which affected even his style. During this third period (1609-1611) he wrote a series of tragicomedies in the manner of Fletcher [Cymbeline (1609), The Winter’s Tale (1610), and The Tempest (1611)]. Psychological analysis and definitely motivated action then began to disappear; grim realism gave way to fairy tale and legend. Shakespeare became preoccupied with the complicated, cleverly constructed plots (Cymbeline) demanded by the public. His plays were once more filled with those purely decorative, esthetic elements—masques, pastorals, and fairy scenes—which abound in the plays of his first period, and are completely absent from those of his second.” The writing of these plays at any other time is almost inconceivable.

In general, however, anti-Stratfordians are not likely to be convinced. Logical argument is not the fundamental issue here; every fact is presented as another element of an immense cover-up. That no contemporary of Shakespeare ever suggested that William of Stratford-upon-Avon was not the author of the plays, that not a shred of evidence connects the Earl of Oxford to the Shakespeare canon, none of this has any impact.

The argument about the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays would not appear, at first glance, to have anything to do with the content and substance of the works themselves. After all, what’s in a name? Whether Francis Bacon, Edward de Vere or William Shakespeare wrote the dramas does not alter a word of dialogue or a single dramatic moment.

However, on deeper reflection, it should be obvious that the historical presentation and critical interpretation of 400-year-old plays are not secondary matters. The contemporary reader or spectator is not likely to have a direct and immediate relationship to such art works. The intellectual “gatekeeper” becomes, or certainly aspires to become, a figure of some importance. To control or direct the discourse about the central figure in the literary culture is no small matter, as the continuing vehemence of the debate demonstrates.

For many of the English anti-Stratfordians of the 19th and 20th centuries, class snobbery was a driving force: Shakespeare the lowly born “petty-minded tradesman” had to be shunted aside and an aristocrat, more in keeping with fantasies about English greatness, put in his place.

That remains an element in contemporary arguments, but it is perhaps not the dominant one, or at least, not directly.

The Oxford advocates and other authorship conspiracy theorists often pay homage to Shakespeare’s greatness. Orloff and Emmerich are generally careful to. HS prefaces his remarks by such a tribute: “The film [Anonymous] is not an attack on Shakespeare. It is a celebration of the magnificent plays and poems of perhaps the greatest writer in the English language.”

Shakespeare is a monumental figure, difficult to assault head on. His work has sunk too deep into the bone and marrow of Western and to a large extent global culture. The apparent irresolution of a Hamlet, the behind-the-scenes scheming of a Lady Macbeth, the oppression and revenge of a Shylock, the vaulting ambition of a Richard III, the boisterous unscrupulousness of a Falstaff… we have inherited these and many others from the playwright not merely as dramatic figures, but essential human types.

Shakespeare’s phrases are even more pervasive in everyday English speech than the expressions used in the King James Bible, the second greatest source of popular idiom. People who have never seen a single performance of one of the 37 plays may nonetheless find it difficult to get by without using such phrases as “a laughing stock,” “dead as a doornail,” “eaten out of house and home,” “a plague on both their houses,” “he wears his heart on his sleeve,” “in the twinkling of an eye,” “send someone packing,” “mum’s the word,” “at one fell swoop,” “it’s Greek to me,” “fight fire with fire,” “good riddance” and a thousand others, all invented or made popular by Shakespeare. The musical adaptations and treatments of Shakespeare works run the gamut from operas by Verdi and Wagner to a ballet by Prokofiev and a musical by Cole Porter.

For this reason, the attack on Shakespeare, and I would argue that the Oxford argument and other such claims are, in the final analysis, all attacks on Shakespeare, has to be carried out at something of an angle.

In our present debased intellectual climate, the attack centers on Shakespeare as an artist of wide-ranging themes and concerns, a Renaissance figure who grappled unflinchingly with the most titanic human questions at the dawn of the modern age. Could there be a greater affront to the postmodern relativist and subjectivist, the practitioner of “identity politics” in art, or the theorist of “difference” and “micropolitics” than a dramatist who knew no national, temporal or gender limits, who dared to write eagerly and passionately about everyone and everything?

Only the most thickheaded choose openly to dismiss Shakespeare as simply another “dead white European male,” but that urge, to one degree or another, is present in many of the critics. The aim, conscious or otherwise, is to diminish and besmirch as close to a universal personality and artist as bourgeois culture produced. The filthy portrayal of Shakespeare as a braggart, a cheat and a murderer in Anonymous is not accidental or merely “over the top,” as even HS admits. It lays bare the real intellectual thrust of the anti-Shakespeare argument: that there is something rotten, hidden, suspect and filthy at the foundation of the culture.

We, on the contrary, are proud to belong to the same species that produced a Shakespeare. It is a source of optimism. It gives us considerable confidence that human beings can tackle any problem, no matter how challenging. It is profoundly reassuring to know that Shakespeare and his body of work exist.

The Elizabethan playwright is an affront in so many ways. His artistic genius seems overwhelming and incomprehensible to the mediocrity unable to view the playwright and his contemporaries historically.

Smirnov, commenting on Christopher Marlowe, wrote eloquently of “the ‘stormy genius’ of the English Renaissance, who died prematurely.” Marlowe’s plays, he observed, “expressed all the passion, all the super-abundance of strength, all the utopian daring of thought and will of a newly-born, exultant class, eager to rush into the fray for the conquest of the world.”

Smirnov (1883-1962), a remarkable intellectual in his own right, was not entirely free from schematism in his analysis of Shakespeare, made in the dark days of Stalinist rule in the 1930s. But he was assuredly correct when he commented that a critical characteristic of the dramatist’s outlook was “a new morality, based, not on the authority of religion or of feudal tradition, but on the free will of man, on the voice of his conscience, on his sense of responsibility towards himself and the world. This called for the emancipation of the feelings and personality of the individual; in particular, this necessitated individualism, that most vital and typical characteristic of the Renaissance, which found its fullest expression in Shakespeare.”

Smirnov had no doubt read Trotsky’s Literature and Revolution. In that work, the author argued that bourgeois society, “Having broken up human relations into atoms… during the period of its rise, had a great aim for itself. Personal emancipation was its name. Out of it grew the dramas of Shakespeare and Goethe’s Faust. Man placed himself in the center of the universe, and therefore in the center of art also. This theme sufficed for centuries. In reality, all modern literature has been nothing but an enlargement of this theme.”

HS’s view of Shakespeare emerges forcefully toward the end of his letter, when he writes: “If you are looking for class distinctions, you have to look no further than the plays and Sonnets. Of the 37 plays, 36 are laid in royal courts and the world of the nobility. The principal characters are almost all aristocrats with the exception perhaps of Shylock and Falstaff. From all we can tell, Shakespeare fully shared the outlook of his characters, identifying fully with the courtesies, chivalries, and generosity of aristocratic life. Lower class characters in Shakespeare are almost all introduced for comic effect and given little development. Their names are indicative of their worth: Snug, Stout, Starveling, Dogberry, Simple, Mouldy, Wart, Feeble, etc. The history plays are concerned mostly with the consolidation and maintenance of royal power and are concerned with righting the wrongs that fall on people of high blood.”

An extraordinary passage, which to a large extent lets the cat out of the bag. It is not clear whether HS approves or disapproves of Shakespeare’s supposed upper class bias. The paragraph suggests a hostile, pseudo-left attitude, but our reader is a proponent of a nobleman having written the “magnificent” plays, so where does that leave him?

In any event, the approach is, first of all, entirely ahistorical. HS apparently assumes we will only approve of an artist who adopted the standpoint of some amorphous “lower class,” a position that would have been out of the question for a prominent artist in the 1590s or early 1600s. Shakespeare identified with the revolutionary class of his day, the bourgeoisie. If he eschewed for the most part an explicitly bourgeois content, as Smirnov explains, that was in keeping with the other extraordinary humanists of his time. “Middle-class themes would not have adequately expressed their ideas and would have restricted the depth and extent of their efforts.” Shakespeare’s hostility toward feudal institutions and conceptions is nonetheless omnipresent in his works.

It doesn’t occur to HS that the playwright’s attitude toward absolutist “royal power,” which in Elizabethan England meant a temporary (and by the end of Elizabeth’s reign, an unraveling) alliance between the bourgeoisie, the gentry (the middle and petty nobility) and other social elements, under the aegis of the Queen, against the great feudal lords, might have a specific and historically progressive content.

As for HS’s comments about Shakespeare’s hostility toward his “lower class characters,” the best antidote is to read or see the plays themselves. One really has to ask whether our correspondent has seriously, thoughtfully read a single one of them. Shakespeare was intimately familiar with the language of the streets, with popular discourse. The lively collection of servants, ostlers, gravediggers, clowns, peasants, porters, landladies, nurses, constables, weavers, village friars, shepherdesses, sailors and simple soldiers that the reader or spectator will find there (whose creation, of course, would have been utterly impossible for the Earl of Oxford), often the soul of wit or common sense, will adequately and definitely put the lie to our reader’s assertion.

The paragraph makes a complete hash of HS’s arguments. If his contentions were accurate, and Shakespeare were some sort of retrograde aristocratic mouthpiece, which of course suits the argument that Oxford wrote the 37 plays, then it would be considerably more difficult to explain in what sense his plays and poems are “magnificent.”

HS can’t have it both ways, although he probably doesn’t realize it. The beauty and freshness of Shakespeare’s language were bound up with (and only explicable in the context of) his own social being—i.e., that he was not an aristocrat on the order of the Earl of Oxford—and the plays’ social and historical substance, that is, that they conveyed the feelings and thoughts of a nascent, world-changing bourgeoisie, which made possible a relentless pursuit and examination of life in all its dimensions.

All in all, I could hardly agree less with the letter from HS.

David Walsh

29 November 2011

* * * * *

Mr. Walsh:

Regarding your review of the film “Anonymous” by Roland Emmerich, I am truly shocked and distressed that a writer whose reviews I have followed for years and whose sharp insights and knowledge has been truly inspiring should simply parrot the shop-worn clichés of the multibillion dollar Shakespeare establishment. It is really unfortunate that you would stoop to such personal attacks on Roland Emmerich, one of the most prominent gay directors in the world and a man I am proud to call a friend, and screenwriter John Orloff. These are men of the highest creativity and integrity who have had the courage to take on the Shakespeare industry whose purpose is only to stifle debate on this issue.

The film is not an attack on Shakespeare. It is a celebration of the magnificent plays and poems of perhaps the greatest writer in the English language. The film’s purpose is simply to set the record straight, to expose the mythology of the uneducated genius from Stratford, and give credit at long last to the true author. The only issue here is not whether you like the idea that a nobleman wrote the works attributed to William of Stratford but whether it is true. The issue is not about class, but about evidence and I believe that the evidence clearly points to Edward de Vere as the true author.

Your statement that Mr. Emmerich “could hardly care less” about the controversy is blatantly false. He is a strong supporter of the idea that the orthodox position is full of smoke and mirrors and does not describe the true author of the Shakespeare canon. Questioning the Stratfordian attribution has been around for over a hundred years as you say for one reason alone—because we have little information about Shakespeare of Stratford that would in any way designate him as a writer, let alone the greatest writer in the English language. The “personal and historical facts” that are “too numerous to mention” do not stand up upon scrutiny.

Biographies of William of Stratford contain one page of fact and 599 of speculation such as “he might have,” “he could have,” it is probable that,” and so forth. The few facts we know about Shakespeare from Stratford are stretched, pulled, and twisted to make it plausible that he was the author. There is nothing in his biography to connect him with the works. Indeed the opposite is true. Robert Bearman sums up Shakespeare’s life as follows in “Shakespeare in the Stratford Records” (1994), published by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust: “Certainly, there is little, if anything, to remind us that we are studying the life of one who in his writings emerges as perhaps the most gifted of all time in describing the human condition. He seems merely to have been a man of the world, buying up property, laying in ample stocks of barley and malt, when others were starving, selling off his surpluses and pursuing debtors in court….”

The fact that some works were published under the attribute of William Shakespeare does not identify the man behind the name. There is nothing in his handwriting ever discovered except for six almost illegible signatures. There are no letters, no correspondence, no manuscripts, no paper trail at all to identify the man behind the name, not a single word. Nobody claims to having ever met the man. When contemporaries refer to William Shakespeare, they are referring to the name on the title page and nothing else. The claim has been refuted by academics whose reputations and possibly their careers are at stake and the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust whose Stratford Tourist bonanza may be permanently derailed.

The list of those who have doubted the Stratfordian attribution contain some of the most prominent authors, actors, and thinkers in American history including Henry and William James, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Mark Twain, Sigmund Freud, Mortimer Adler, Mark Rylance, Derek Jacobi, Charles Dickens, Walt Whitman, Supreme Court Justice Henry Blackmun, Harvard Professor William Y. Elliott, Clifton Fadiman, John Galsworthy, and many others. See http://doubtaboutwill.org/past_doubters.

Anonymous is in no way a “deeply mean-spirited work.” It is fiction but one designed to begin to set the record straight on the true authorship of the Shakespeare canon. Mr. Emmerich has stated that his film provides one possible alternative explanation of the fact that we know next to nothing about the great Shakespeare, not the only explanation. The film does not present anyone in the abusive terms you mentioned. Ben Jonson is shown as a person of great dignity who suffered the consequences of a totalitarian monarchy that routinely closed theaters and threw writers into the Tower for alleged political crimes, similar in a way to the treatment of artists in Iran such as Jafar Panahi.

It is a fact that Christopher Marlowe was murdered, most likely under the direction of the repressive state that wished to stifle dissent. While the film’s treatment of Shakespeare is admittedly a bit over-the-top, the evidence points to the fact that he was an opportunistic play broker who was willing to take credit for the works of another man.

As far as 1604 is concerned, the year that Oxford dies, no source for any Shakespearean play is dated after 1604. No sonnets were written after 1604. Between the years 1593 to 1604, seventeen plays attributed to Shakespeare were published. From 1605 to 1623 there were only five, said to be collaborations.

You have chosen to make this into a class issue and bring up the familiar straw man argument about snobbery. The issue is about evidence, not about class. The assumption behind the support for William Shakespeare of Stratford as the author has to be that he was no ordinary mortal because otherwise there is no accounting for the detailed knowledge of the law, foreign languages, Italy, the court and aristocratic society, and sports such as falconry, tennis, jousting, fencing, and coursing that appears in the plays. I do not have any doubt that genius can spring from the most unlikely of circumstances. The only problem here is that there is in this case no evidence to support it. Would the greatest writer in the English language have allowed his daughters to remain illiterate?

If you are looking for class distinctions, you have to look no further than the plays and Sonnets. Of the 37 plays, 36 are laid in royal courts and the world of the nobility. The principal characters are almost all aristocrats with the exception perhaps of Shylock and Falstaff. From all we can tell, Shakespeare fully shared the outlook of his characters, identifying fully with the courtesies, chivalries, and generosity of aristocratic life. Lower class characters in Shakespeare are almost all introduced for comic effect and given little development. Their names are indicative of their worth: Snug, Stout, Starveling, Dogberry, Simple, Mouldy, Wart, Feeble, etc. The history plays are concerned mostly with the consolidation and maintenance of royal power and are concerned with righting the wrongs that fall on people of high blood.

Edward de Vere was not a “jaded aristocratic.” He was a recognized poet and playwright of great talent who was singled out in 1598 as being “best for comedy.” Oxford was a man of the theater and a patron of the arts who operated two successful playing companies: Oxford’s Men and Oxford’s Boys. Although no play under Oxford’s name has come down to us, his acknowledged early verse and his surviving letters contain forms, words, and phrases resembling those of Shakespeare. The Shakespeare plays and poems show that the author had specific knowledge of certain works of literature, certain prominent persons in Elizabeth’s court, and events connected with them. In the sonnets and the plays there are frequent references to events that are paralleled in Oxford’s life.

You seem to base your knowledge on the claims of the entrenched academic orthodoxy that have, with some exceptions, refused to treat the issue with the seriousness it deserves. Your “review” is simply an emotional rant that really makes me wonder if you have ever read a book on the life of Edward de Vere and the case for his authorship which in my view is not only strong. It is compelling.

Howard S

Vancouver, British Columbia

23 November, 2011