Directed and filmed by Zhao Liang

Like most artistic endeavours in China, serious filmmaking is a perilous business. Mainstream domestic movies must be authorised in advance by the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) bureaucracy. Directors are also forced to accept modifications demanded by the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television during production if they want their work screened in any of the country’s 6,500 cinemas.

While these procedures have a noticeably deleterious impact on the content and artistic veracity of contemporary Chinese cinema, the last 15 to 20 years have seen the emergence of an independent documentary film movement operating outside the official production and distribution system.

Access to these films, unfortunately, is severely limited in China. Many are banned outright or only shown to limited audiences at semi-official or unofficial screenings. Others are distributed via China’s unregulated DVD market. Apart from screenings at international film festivals and a handful of other smaller-scale events, the “New Documentary Movement” is also largely unknown to Western audiences.

Taking advantage of mini-DV cameras and other advances in low-budget production, scores of filmmakers, many without any previous experience, have produced some interesting films exploring lesser known aspects of life in contemporary China. Much of this work is motivated by a healthy desire to record the vast social changes underway, concerns about the plight of workers and other marginalised layers, and various inchoate oppositional sentiments toward the CCP regime.

As one commentator notes in a recent collection of essays entitled The New Chinese Documentary Film Movement: For the Public Record: “The new documentaries created a vision of ‘reality’ in contrast to what they viewed as the fake, exaggerated, and empty characteristics of not only the old socialist realist documentaries but also the more recent special topic programs. They viewed their documentaries as a challenge to, and a rebellion against, the officially sanctioned special topics programs.”

One of the better-known documentaries from this genre is Petition: The Court of the Complainants (2009), which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2010 and is now available to Western audiences on DVD. Directed by Zhao Liang, the movie explores the plight of a disparate group of poverty-stricken “petitioners” attempting to reverse various injustices committed against them by the authorities and employers. Zhao, who shot the documentary over a 12-year period, takes viewers into the Kafkaesque world of bureaucratic arrogance, indifference, corruption and violence that constitutes China’s petition appeal system.

Petitioning appeals originated during the Ming Dynasty and were a political mechanism for the imperial state apparatus to hear, and occasionally address, injustices perpetrated against the emperor’s subjects by lower-level officials. In 1951, the CCP introduced its own version of this political safety valve, with a network of local and regional petitioning offices. The final adjudicating authority was located at the State Bureau for Letters and Visits in Beijing.

Zhao does not provide a detailed exposition or commentary on this phenomenon. His observational-style documentary, however, explores the desperate, hand-to-mouth existence of those living at “Petition Village,” the network of squalid rooms, tents, huts and other rough accommodation that was home to petitioners near the Beijing South railway station when he began filming in the mid-1990s.

Some of the documents required by petitioners

Some of the documents required by petitionersA petition appeal involves lodging countless documents, signatures and forms—first with local authorities and then the Beijing office—a sanity-destroying procedure and one designed to last for years. Few, if any, of these cases get beyond this seemingly endless process.

A survey in mid-2000 reported that less than 0.2 percent of petitioners even received an official response to their complaints. Despite this, the number of petition appeals has grown annually—from 4.8 million in 1995 to 12.7 million in 2005—in line with increasing exploitation by local and foreign-owned corporations, privatisation of state-owned industries and land, rising unemployment and worsening social inequality. Recent statistics estimate that annual petition submissions are now in the tens of millions.

Petition focuses on a handful of characters who tell their stories. These include a landless farmer, a victimised teacher, a young man paralysed after he was badly beaten by prison guards, and a mother and grandmother seeking justice for family members.

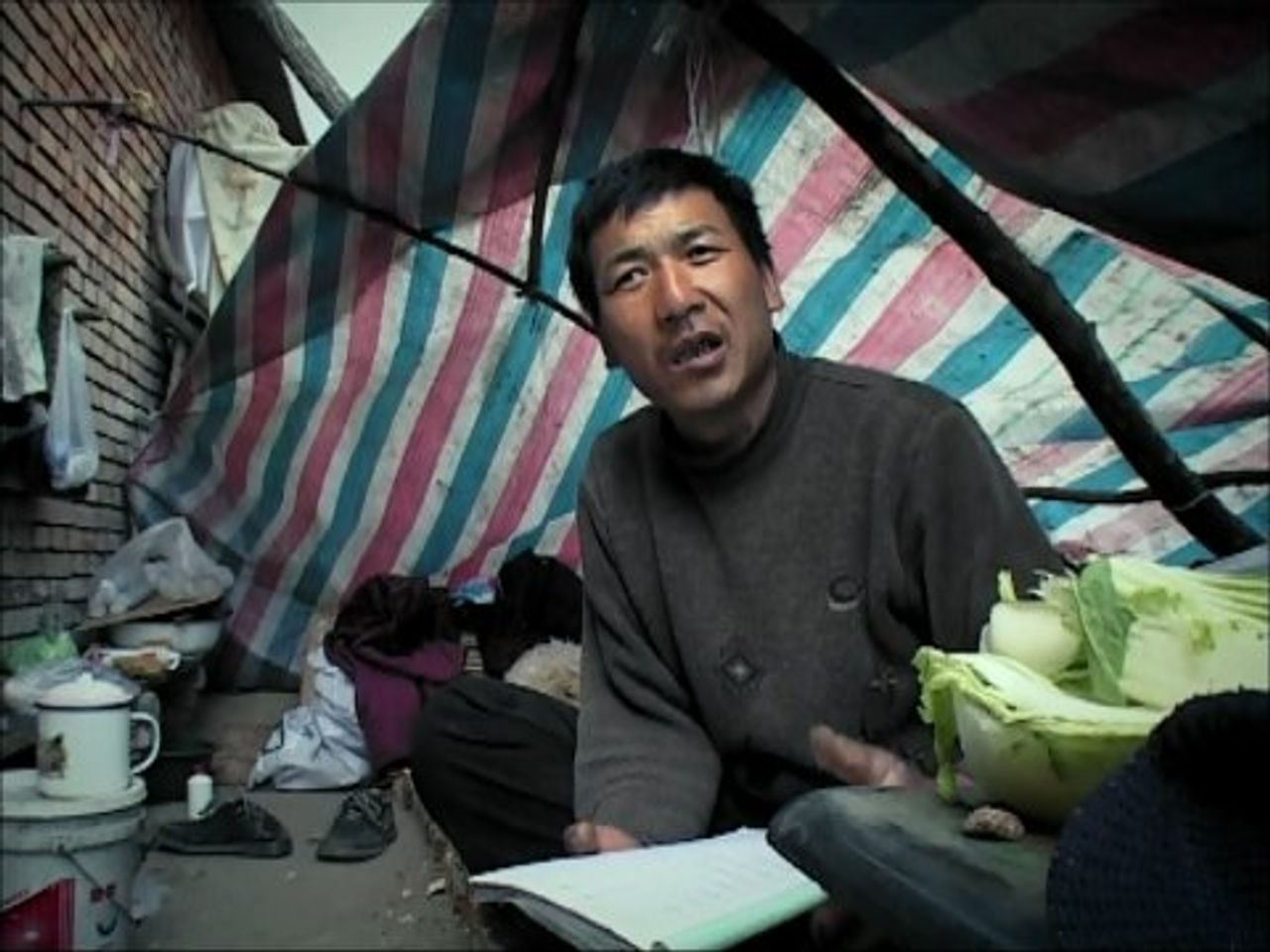

Petitioner explaining his story

Petitioner explaining his storyZhao’s two-hour film—the Chinese original is over five hours—also contains footage secretly shot inside the State Bureau for Letters and Visits. Faceless clerks hidden behind heavy glass arrogantly dismiss petitioners; anyone complaining about their treatment is violently ejected from the building by security guards.

Bribery and corruption operate on every level, from the petty clerks and local police to the menacing “retrievers.”

The “retrievers” are well-paid thugs employed by regional bureaucrats to prevent petitioners taking their complaints to the central government authorities. Beatings, kidnappings and even murder are common and the film has footage showing dark-suited “retrievers” roughing up and attempting to kidnap petitioners. “People won’t notice if you disappear,” says one retriever to a petitioner. These scenes are contrasted with a brief extract from a nationally-televised New Year address by President Hu Jintao who declares that “everyone is prospering in China.”

Zhao’s documentary contains a horrifying scene of petitioners searching for the body parts of a couple from Inner Mongolia who were killed by a train as they desperately fled police. The tragedy leads to an angry protest by petitioners and some supporters. One young man declares: “We have to find a way to show that the petition system is a lie.” Another calls for a revolutionary overthrow of the government and the establishment of democratic rights. The protest organisers are later arrested and jailed.

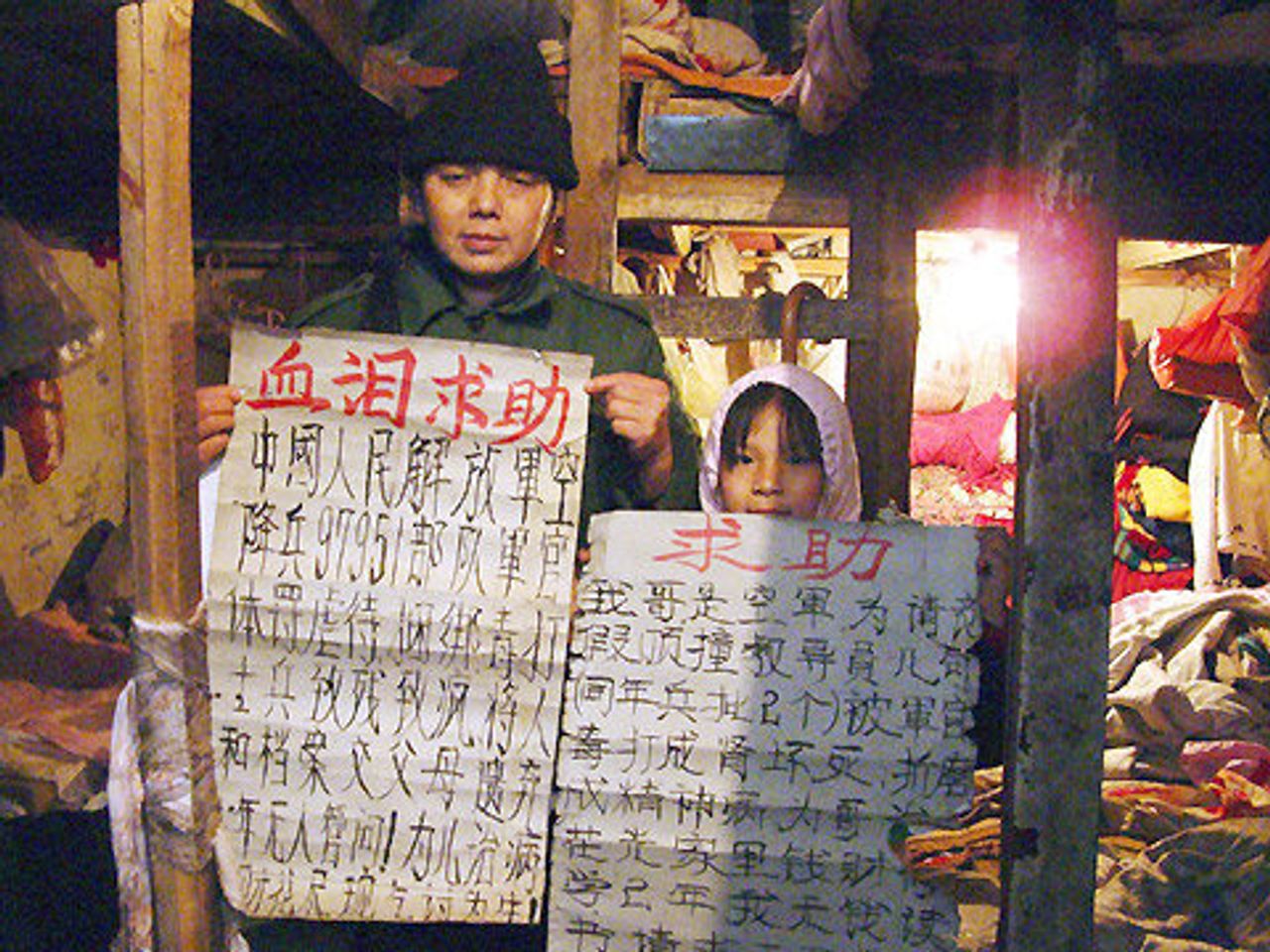

Qi and daughter Xiaojuan. Placards read 'Appeal for help with blood and tears'

Qi and daughter Xiaojuan. Placards read 'Appeal for help with blood and tears'One of the documentary’s more poignant elements is the complex relationship between Qi and her teenage daughter, Xiaojuan. The middle-aged mother explains that she has been petitioning for over ten years for an investigation into the mysterious workplace death of her husband. The daily grind to find food and shelter in Beijing has prevented Xiaojuan from gaining any formal education. After years of this misery, the young girl decides to leave her mother and go back to the provinces. She later returns with her own child and there is a moving reconciliation.

The final part of Petition unfolds amid government preparations for the 2008 Olympics. The old Beijing South rail station and the nearby petitioners’ shanty towns are demolished to make way for a new station. Some petitioners are dispersed by police to Beijing’s outer suburbs. Others, including Qi, are locked up in mental health institutions. The movie ends with a distant view of the multi-million dollar fireworks of the opening ceremony.

Zhao, 41, was born and raised in the China-North Korea border town of Dandong. After studying at the Beijing Film Academy, he began his career as a video artist, photographer and then screenwriter, before making his first documentary in 2001. The director has recently been criticised by several independent Chinese filmmakers for collaborating with state authorities to produce a documentary entitled Together, on the plight for HIV sufferers in China. Zhao’s movie reportedly fails to mention the years of discrimination against HIV patients by the authorities.

Nevertheless, Zhao’s Petition is a courageous and damning indictment of the CCP regime and the so-called petition appeal system. The documentary reveals that the stubborn but false of hope of petitioners—that someone in the bureaucracy will eventually listen—is tragically utopian. The Stalinist apparatus is impervious to the plight of ordinary people and incapable of “reform.”

Petition is available in the US on DVD from dGenerate Films. It has been released in France as part of a three-disc collection that includes Zhao’s Crime and Punishment (2007), about young military police on the China-North Korea border, and Paper Airplane (2001), which examines the life of Beijing heroin addicts.