The WSWS spoke to Mahdi Fleifel, writer and director of A World Not Ours, and Patrick Campbell, co-producer (along with Fleifel) of the film, in Toronto.

Mahdi Fleifel and Patrick Campbell

Mahdi Fleifel and Patrick CampbellDavid Walsh: How did this particular film come to be?

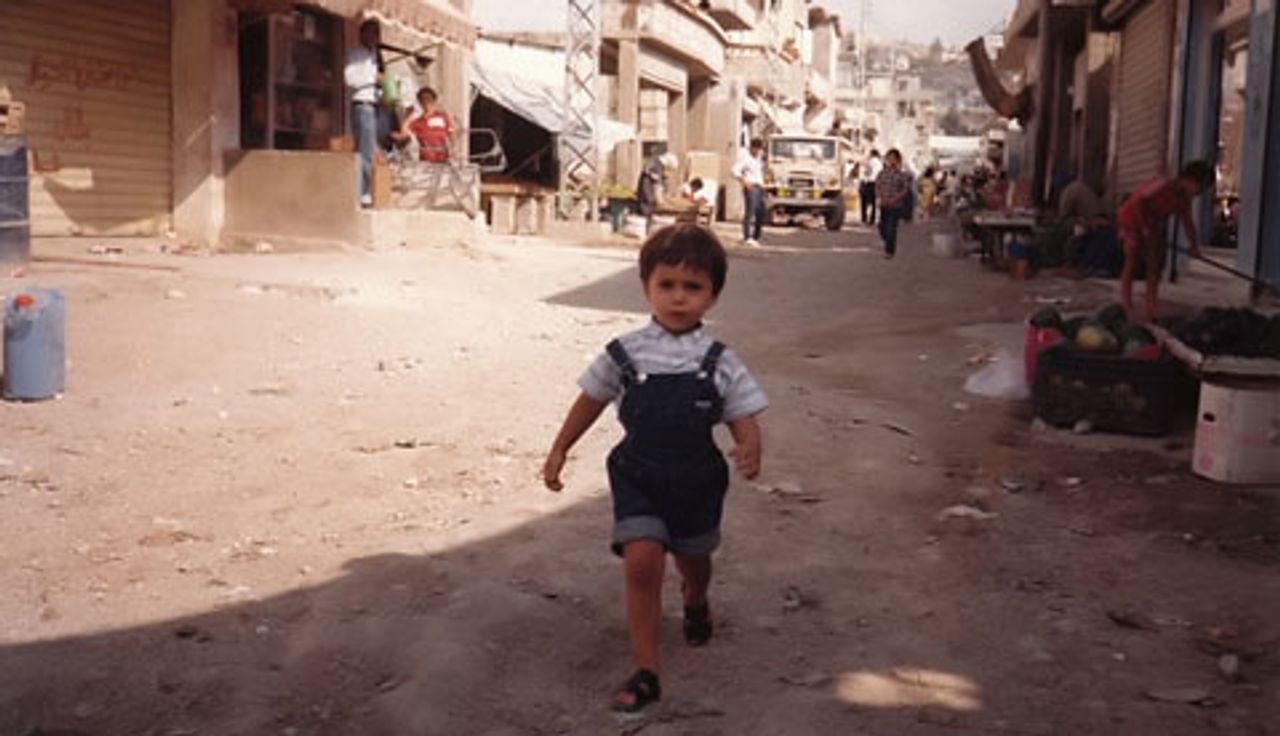

Mahdi Fleifel: This film has been around as long as I’ve been around, without my noticing it. After my last trip to Ain El Hel-weh [Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon], I realized I’d been personally recording there for 12 years. My father had been filming since the mid-1980s. and it hit me that perhaps I had a story in all this footage.

Initially, we were talking about doing a fiction film. I trained as a fiction director. This was my first documentary, almost by default. It occurred to me: what’s the point in trying to write a fiction film and cast someone who reminds me of my granddad, or my friend, when actually the real deal is right there in front of me?

There were something like 150 hours of footage, in different formats. VHS, Super-8, HD.…

A World Not Ours

A World Not OursPatrick Campbell: We were working with a wonderful editor, but he didn’t speak Arabic, so that was an added complication. Some 150 hours of footage that he didn’t quite understand. We’ve basically been sitting in the same room for two years.

DW: Perhaps for the benefit of the readers, could you explain a little about your family and personal history?

MF: The story begins with the nakba [disaster] for the Palestinians in 1948. This is the “big bang,” it’s where I see my narrative beginning.

In 1948, my grandparents, on both my father’s and mother’s side, went north and ended up in Lebanon. They settled in the Ain El Hel-weh refugee camp. If people were from the same villages, they gravitated to one another. My mother’s and father’s families were from the same village, Saffourieh.

My grandparents were driven out in 1948, and my parents were born in Ain El Hel-weh. In the 1970s, they got married. Many Palestinians at the time would go and look for work in the Gulf. My dad went to the United Arab Emirates. He didn’t really bother himself with politics, or the PLO. He was kind of a salesman, he worked for Kodak, and he sold chocolate at one point.

We stayed in the Emirates until the mid-80s, but things weren’t quite working out. It was decided we would return to Ain El Hel-weh, while my father continued working there. In the late 1980s, the Scandinavians opened the door to quite a lot of immigrants from the Middle East. Palestinians from Lebanon in particular went to Sweden, Denmark and, to a certain extent, Norway. None of us in the camp had ever heard of Scandinavia, or Denmark.

My dad came back from the Emirates. He said, “It’s all done, we’re going to this place called Denmark.” We were taken out of schools. We went to Denmark in the early winter of 1988. We stayed, I think, two weeks in an asylum center and were granted permanent residency. We were taught the language, we got a home. It was very secure and comfortable, and really what my parents were looking for.

But that changed as well, because their lives seemed to stop in some sense, because of the language, culture and other issues. I was nine, I picked up the language. I went to school and high school, and after high school, I felt like I wasn’t particularly excited about being in Denmark, there were a lot of family issues, a divorce. I decided to come to the UK and study film.

Eventually I found my way to London. I’d grown up in Dubai, which at the time was a desert. We had a small, air-conditioned flat, the bus would drop me off after school and that would be that. And from there, it was the camp, which, again, was a small, confined space. In Denmark, we ended up in a very small town, on the outskirts of Elsinore. After that, I lived in Newport in south Wales. So coming to London was a big change that shook everything up. I felt at home, because for the first time I didn’t have to worry about whether I was Palestinian or Danish....

DW: What is your relationship to the refugee camp now?

MF: For me, it’s been conflicted. The camp has changed over the years. As a kid, it was the best place to visit. There were a few summers that we didn’t go, and it just felt that the year was ruined. It was like being in a perpetual festival. Everyone knew each other. At the time, pre-Oslo [Accords in 1993], there was still an idealism, a feeling for the revolution that was still there.

In terms of the physical conditions in Ain El Hel-weh, you have to bear in mind that the population has grown over the years, but the space has not. It can only expand upward. Three generations have now built houses on top of each other.

The ambiance today is different, it’s quite tense. You can hear the neighbors snoring, there is no privacy. And this is one of the difficult things for older people, like my granddad, who’s in his 80s and just wants to be able to relax.

My mother doesn’t have any ties with the camp any more. She left when she was 18, she got married, she never looked back. All her siblings live in Canada, Germany, Denmark. Whereas for my father, the camp was where his heart was, that was his home, he never felt at home in Denmark or Dubai. So I have both sides.

DW: You’ve obviously held on to it in some ways.

MF: It occurred to me on that trip in 2000 that this was not Disneyland, but something much more complicated. When I was younger, it was strange, because here I was filming this place, but no one had heard of it. I’d come back from Lebanon, and I’d try to explain it to my classmates in Denmark. As soon as they heard “refugee camp,” they’d say, “Is it somewhere in South America?” “No, no.” So I’ve always had this need to explain, to show people what it’s like. The sad thing is that people in Lebanon don’t even know what it’s like inside a camp.

Ain El-Hel-weh is the largest camp in Lebanon, it’s in the south, about an hour and a half from the Israeli border, halfway between Beirut and the border.

PC: It’s also one of the few remaining autonomous camps. Although they’re not as well-armed as they were, the PLO is still armed and the Lebanese state wouldn’t really get into it very much, whereas they’ve either destroyed the other camps, or they’ve integrated them. Ain El Hel-weh is one of the last authentic Palestinian spaces left in Lebanon.

MF: In the 1982 Israeli invasion, it was completely flattened. I have pictures of my auntie smiling into the camera while she’s trying to find stuff in the rubble of her house. Then you had the camp wars, involving the Syrians. Everything that played out in Lebanon played out in the camps as well. The Palestinians were used for various purposes.

DW: What do you think lay behind your father’s obsession with filming?

MF: I’ve always wondered about that. My father was the youngest boy in a family of nine or ten. He was one of the youngest, in his mid-20s in the 1970s. He loved movies, he loved heist films, action films, he loved to dress like John Travolta.

Subconsciously, I think he felt a need to keep a record of our lives. There was always this obsession in my family. And everyone in Ain El Hel-weh knows about it. When I’m there, I hear it all the time, “You’re just like your dad.” I’m not sure whether it’s meant as a compliment or not.…

DW: The three central figures, your grandfather, your uncle Said, and your friend, Abu Iyad, emerge very strongly as human characters, as personalities. Is your grandfather still persevering?

MF: He’s sort of mellowed over the years, but I think there’s no way he would leave the camp. I think it’s hard for any of us to imagine what a tormenting experience it must have been to be uprooted like that, in 1948. My granddad was 16. They had to leave everything. Homes, land, possessions. You sense that when you sit with some of the older people. Somehow they’ve never grown, emotionally they’re frozen.

DW: What about your uncle Said and his brother Jamal, that seems another trauma?

MF: Making this film was the first time I grieved for Jamal, because I wasn’t really aware of what happened at the time.

DW: Did you know him?

MF: I knew him, he was this hero. Incidentally, one of the greatest break-dancers I’ve ever seen. There was something very charismatic about him. He was powerful looking, good-looking, everyone had this respect for him. And he was a tough kid. He was a legend, what he’d done at such a young age. Everyone knew him in Ain El Hel-weh.

There wasn’t a big age difference between him and Said, and Said, being the younger brother…not only was there the general looking up to him, but this was his brother! So I think Said changed completely when his brother died.

He has a great heart, and so generous. He wants people to approve of him, he gives away his birds, he’d give away anything. He has a beautiful soul. Severely damaged.

DW: Which conflict was Jamal shot in?

MF: It was in 1991.The civil war ended, and the Lebanese army tried to clean up the problems. And one of their efforts was to try and enter Ain El Hel-weh, which didn’t work out, and they’re still resentful about that. So it was ’91, and the Lebanese army opened a front and Jamal went out to do his thing. My grandmother used to tell me that she saw him in his combat outfit and she told him not to go. But he was hot-blooded. He was only 22, 21. He hadn’t matured yet, there was still this sort of recklessness.

PC: He only knew war.

MF: He was shot by a sniper and died painfully a year and a half later. We got the news about Jamal when I was 10 or 11 years old in Denmark. He got thinner, couldn’t eat. He was far away from me. And his situation was very tough. I don’t know how he survived that long.

DW: The third personality, and in some ways the most complex, is Abu Iyad, the former Palestinian militant. His situation speaks most directly to some of the present-day difficulties.

MF: He’s very smart, he has a sixth sense. From a very young age, he became involved in intelligence work, they would send him out to sniff out this or tell them about that.

DW: His disillusionment is not simply a personal discouragement, something is at a dead end there. There is a Palestinian elite that wants to get rich. They are envious of the Saudis and others, they want to have their own country so they can exploit the population and make lots of money.

MF: Exactly. When the PLO left Lebanon in ’82, then went to Tunisia, and eventually found themselves settling back in Ramallah, everyone forgot the people in Lebanon. The expatriates, the ones who accumulated a lot of money in exile, doing whatever they did, whether it was in Tunisia or Eastern Europe, or wherever, found their way back and now they’re opening hotels and bars, and sending their kids off to study in the US.

PC: The diaspora became a bargaining chip. With the Oslo agreement in 1993, it became “I’ll give you this for that.” The “right of return”—we were just speaking about the suspended reality of the older generation—is a bargaining chip between the Palestinian elite and the Israelis, or the US, or whoever. That’s part of the reason for Abu Iyad’s disillusionment. He’s essentially been betrayed.

MF: His whole history, his sacrifices have made him feel, “Hang on, I’m genuinely interested in going all the way, and everywhere I look, I see leaders and people chickening out. My god, I’ve given everything for this. I dropped out of school, because I really believe in this, and yet no one is actually doing it. Where do I go from here?” That’s essentially how I see it.…

DW: That comes across. And that’s the question of questions.

MF: The camp’s our home, but it’s not. It’s on loan.

For Abu Iyad, it didn’t work out for him in Athens or anywhere else, but I don’t know if it could. I have friends who have been in Belgium for five, six years, but they don’t know how to function. They didn’t even know how to function outside of the camp in Lebanon, where they spoke the same language, had the same culture.

One of my cousins had a canary. He trained it to leave the cage, he gradually expanded its space, so the bird could fly in the living room, making sure that the windows were closed. During the 2006 war, the door to the balcony was open, and my cousin came in and saw the bird on the balcony, and he said, “Come back, come back.” The bird hesitated, and then it flew out. He said that most likely it would die, because the expansion of space was just too overwhelming. I’ve always thought of this as a metaphor for what happens when you leave that 1-square-kilometer space.

Many a time, Abu Iyad and I would drive out to the river, maybe a half-hour away, and when we were coming back through the check-point, there was a sense of relief at being back in the camp. There’s also a sense of shame, Lebanese people look at you differently. “Oh, you’re a refugee from one of those camps.” You’re a Palestinian refugee, all you have is this blue ID. You’re not part of Lebanese society, you can’t work. Except perhaps in the black market, or for NGOs.

PC: There are certain jobs you can do, but many things are barred to you. If you’re a Palestinian, you can’t be part of the Lebanese political landscape.

DW: What other films would you two like to make?

PC: We have a fiction in mind, following on from Abu Iyad’s story. It’s the story of these guys who leave the camp and end up in Greece. So they’re dealing both with being refugees in Europe and the social collapse in Greece. It’s kind of a double whammy. You’re going to go from one situation of hopelessness to another. What do you do?