Iraq's decision to allow the resumption of UN weapons inspections has temporarily forestalled a US attack. But the crisis is by no means resolved. It will intensify in the coming days and weeks, under conditions in which the Clinton administration has openly linked its preparations for an air war to the goal of destabilizing and removing the regime of Saddam Hussein.

Powerful geo-political interests are fueling the American war drive. In many respects US policy in the Persian Gulf is driven today by the same considerations that led it to invade Iraq nearly eight years ago. As a 'senior American official'--most likely Secretary of State James Baker--told the New York Times within days of the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait in August of 1990: 'We are talking about oil. Got it? Oil, vital American interests.'

The Bush administration exploited Iraq's move against its southern neighbor to demonstrate US military supremacy and strengthen its position in a region rich in oil and strategically located at the crossroads of the Middle East, southeastern Europe, northern Africa and Central Asia. The gulf war was intended as a warning to American imperialism's major international rivals, above all Germany and Japan, both of which were heavily dependent on oil imports from the region. In the midst of the war Bush hinted as much in a speech to the New York Economic Club. In trade talks with Germany and Japan, he said, 'We will have some--I wouldn't say leverage on them--but persuasiveness.'

There have, however, been major changes since 1991, above all, the breakup of the Soviet Union. This gigantic fact has altered geo-political relations in the Middle East, the Persian Gulf and Central Asia, and, if anything, exacerbated American dissatisfaction with the status quo in Iraq.

The transformation of former Soviet republics in the region into independent states--politically unstable but endowed in some cases with enormous deposits of oil and other mineral wealth--has led to an increasingly intense involvement of the US in Central Asia. The lure of enormous oil reserves in the Caspian Sea has made Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan the focus of fierce competition between the great powers of the world for domination of this part of the globe.

This struggle recalls the protracted conflict between Britain and Russia at the end of the nineteenth century for hegemony in the Middle East and Central Asia that became known as the Great Game. Germany made its own thrust into the region with its decision to build the Berlin to Baghdad railroad. The resulting tensions played a major role in the growth of European militarism that erupted in World War I.

This time American imperialism is the major protagonist. Over the past several years, the battle for dominance in the region has come to center on one question: where to build a pipeline to move oil from the Azeri capital of Baku to the West.

Within the next several months the Azerbaijan International Operating Company (AIOC), a consortium of the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan and international companies including British Petroleum and four US firms, Amoco, Unocal, Exxon and Pennzoil, will announce a decision on pipeline construction that Washington considers to be of immense importance to the strategic position of the United States in the twenty-first century. French, Japanese, Russian and Chinese firms are also heavily involved in projects for drilling and shipping oil from the Caspian.

The Clinton administration has given the highest priority to this issue. Bill Richardson, who as American ambassador to the UN was the point man for Washington in the last US confrontation with Iraq in the winter of 1997-98, has been appointed Secretary of Energy. He has been assigned the lead role in convincing AIOC to build its pipeline along an east-west route preferred by American policymakers.

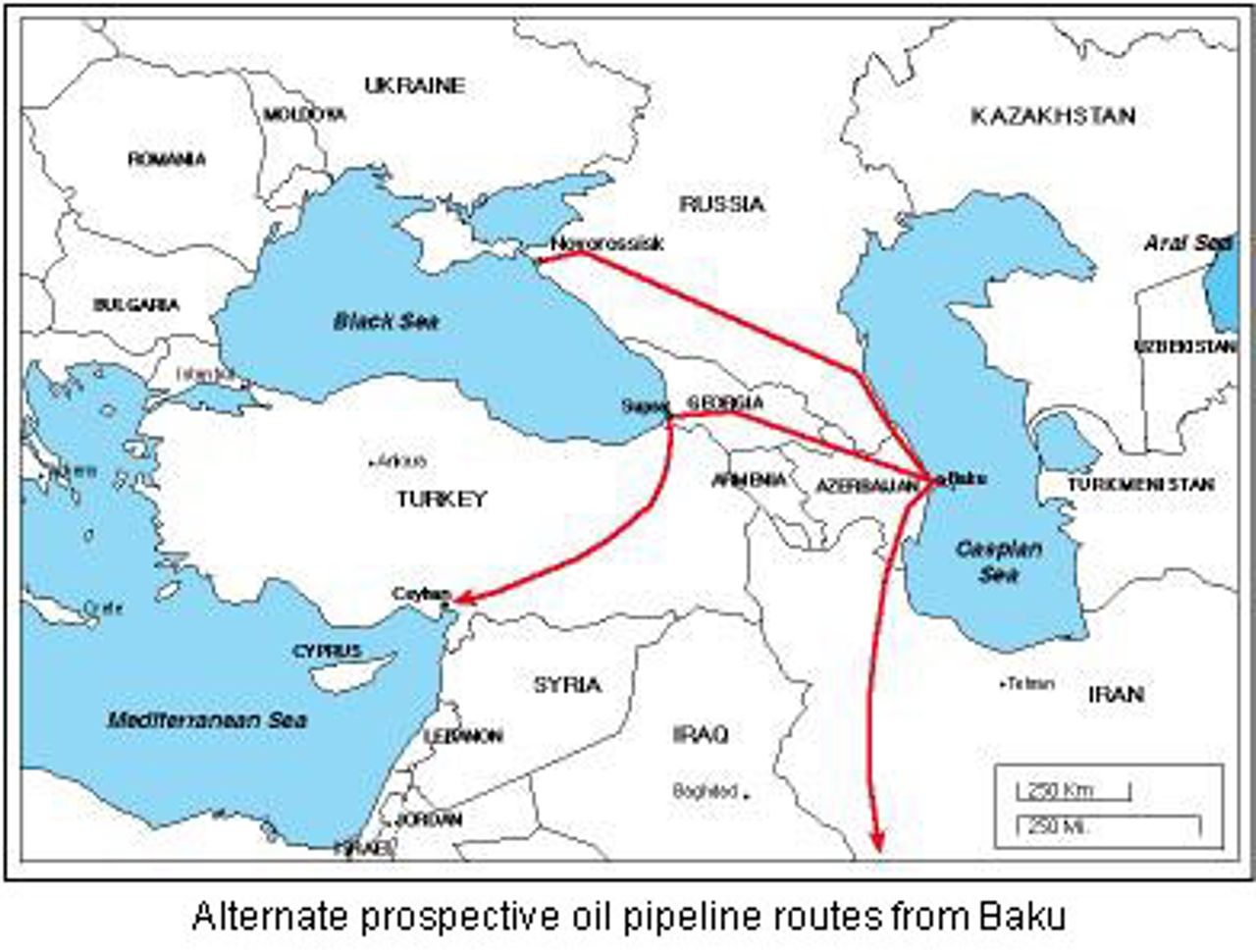

Washington wants the pipeline to pass from Azerbaijan through Georgia to Turkey, emptying out at the Turkish Mediterranean port of Ceyhan. Oil executives have inclined to a more direct, shorter and cheaper route that would flow south through Iran to the Persian Gulf. A third alternative would move the oil from Baku northwest through Russia, ending at the Black Sea port of Novorossisk.

A US State Department report from April of last year indicates the importance which the Clinton administration attaches to the geo-politics of Caspian oil:

'The Caspian region could become the most important new player in world oil markets over the next decade. The US has critical foreign policy issues at stake--the increase and diversification of world energy supplies, the independence and sovereignty of the NIS [Newly Independent States] and isolation of Iran.'

A series of unusually frank articles in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal and other more specialized organs of American bourgeois opinion and policy have placed the battle over the pipeline decision within the context of a struggle for world domination in the next century.

Last month the Times ran a front-page article warning that the US pipeline plan was on the brink of defeat. The article said:

'The Caspian region has emerged as the world's newest stage for big power politics. It not only offers oil companies the prospect of great wealth, but provides a stage for high-stakes competition among world powers.... Much depends on the outcome, because these pipelines will not simply carry oil but will also define new corridors of trade and power. The nation or alliance that controls pipeline routes could hold sway over the Caspian region for decades to come.'

The Times quoted Senator Sam Brownback (R-Kansas) lamenting that US leverage had been weakened because Clinton had 'lost the power of moral persuasion' as a result of the scandals surrounding his administration.

Since then the Clinton administration has intensified its lobbying efforts, and the AIOC has put off announcing its decision on the pipeline route. Indicative of Washington's high-level efforts, the Times ran another major article on November 8, which spoke of the pipeline decision in even more apocalyptic terms:

'At stake is far more than the fate of the complex Caspian region itself. Rivalries being played out here will have a decisive impact in shaping the post-Communist world, and in determining how much influence the United States will have over its development.'

The article quoted Richardson, who hinted broadly at the determination of Washington to prevent the pipeline from running through either Iran or Russia, so as to limit the political influence of both in the region:

'This is about America's energy security, which depends on diversifying our sources of oil and gas worldwide. It's also about preventing strategic inroads by those who don't share our values. We're trying to move these newly independent countries toward the West. We would like to see them reliant on Western commercial and political interests rather than going another way. We've made a substantial political investment in the Caspian, and it's very important to us that both the pipeline map and the politics come out right.'

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the discovery of huge oil and gas reserves in the Caspian have led to a certain evolution in US policy toward Iraq. As long as the issue of strategic concern was only the Persian Gulf, the focus of American concern was to Iraq's south. Washington concluded that a military occupation of Iraq and possible fracturing of the country posed too great a risk of destabilizing the region. It decided at the end of the gulf war to leave Saddam Hussein's Republican Guard intact and allow him to remain in power.

America's intensified interest in the lands to Iraq's north has altered US military and economic priorities. For a thrust into the Caspian, a more direct military and political presence in Iraq is necessary.

Iraq occupies a strategic position in the geography of the region in general, and the geo-politics of the pipeline dispute in particular. The nation that controlled the north of Iraq would be in a position, for example, to protect a pipeline through southern Turkey, or launch military strikes against a pipeline through Iran.

The US would like to turn northern Iraq into a new base for American military operations. This is politically unfeasible as long as the present Iraqi regime is in power. US policy over the past seven years has made a normalization of relations with Saddam Hussein impossible, for both domestic and international reasons. He has become an increasingly intolerable obstacle to American aims. He must be eliminated and replaced by a US client regime.

It is more than just a coincidence that Washington stepped up its military preparations against Iraq at the very point that its efforts to impose its choice of a pipeline route for Caspian oil seemed headed for defeat. A large-scale strike against Iraq would send a clear message to Russia, France, Iran and other rivals that the US retains military supremacy and is prepared to use it. It would demonstrate to each and all that American imperialism is the top gun not only in the Persian Gulf, but in Central Asia as well.

On a wider international arena, conflicts between the US and its imperialist rivals in Europe and Asia are intensifying over a host of economic and political issues. Just in the last few days Clinton has threatened trade war measures against Japan over steel and the European Union over bananas. This provides an added incentive for using Iraq as a convenient target to remind the world of America's capacity for military destruction.

See Also:

US moves towards air attack on Iraq

[10 November 1998]

Earlier 1998 articles on Iraq