This is the second and concluding part of the opening report to the World Socialist Web Site and Socialist Equality Party Conference “Political Lessons of the War on Iraq: the way forward for the international working class” held on July 5-6 in Sydney, Australia. The report was delivered by Nick Beams, member of the WSWS International Editorial Board and national secretary of the Socialist Equality Party in Australia. Part 1 was published on July 10.

While the collapse of the Soviet Union provided the conditions for the US to try to realise long-held strategic objectives, we cannot simply ascribe the eruption of imperialist violence to opportunistic political motivations.

Great changes in international relations—in the very structure of the world capitalist order, for that is what we are dealing with here—have their origins in the economic foundations of the capitalist system, and, in the final analysis, are the expression of deep-seated contradictions within it.

This presents us with something of a challenge: how do we grasp and elucidate the relationship between the economic driving forces of the capitalist system and the historical process?

In the case of the war on Iraq, many opponents, including the World Socialist Web Site, have rightly pointed to the decisive significance of oil. There is no question that the establishment of global hegemony by US imperialism necessitates control of the world’s oil supplies, above all in the Middle East. Having said that, however, it should be emphasised that the economic driving forces at the heart of this war and the wider push for global hegemony extend far beyond oil. Above all, they are rooted in an historic crisis of capitalism itself.

In order to demonstrate this, we must consider the relationship between processes taking place at the very heart of the capitalist system of production—above all, the laws governing the accumulation of profit—and the course of historical development.

By this I do not mean to suggest that every historical event can be traced back to the immediate operation of some economic interest. Rather, the task is to show how economic processes have shaped each historical epoch and given rise to the problems that are then tackled in the sphere of politics.

If we consider the economic motion of the capitalist economy, we see first of all the operation of the business cycle—the succession of booms, crises, recession, stagnation and recovery—that has been evident since the beginning of the nineteenth century.

But if we step back and take a wider view, it is clear that in addition to the short-term business cycle, there are longer-term processes that shape the economic environment of whole epochs.

The post-war boom, which stretched from 1945 to 1973, is qualitatively different from the present period. Likewise, the period 1873 to 1896 is different from the period 1896 to 1913. The former has gone down in history as the Great Depression of the nineteenth century, while the latter is known as the belle époque. And this period was, of course, fundamentally different from the 1920s and 1930s, despite all the endeavours of capitalist governments to return to the pre-war expansion.

What then is the economic basis of these longer phases, or segments, in what Trotsky called the curve of capitalist development?

They are rooted in fundamental processes. The driving force of the capitalist economy is the extraction of surplus value from the working class. This is accumulated by capital in the form of profit. Capitalist production, it must be emphasised, is not production for use, or for economic growth as such, but for profit—the basis of capital accumulation. The rate at which this accumulation can take place, measured broadly by the rate of profit, is the key indicator of the health of the capitalist economy and its overall regulator.

The periods of capitalist upswing in the curve of capitalist development are characterised by a regime or methods of production which ensure accumulation at a rising or steady rate. The business cycle does not cease to operate in such a period. In fact, it functions in such a way as to assist the upswing. Recessions clear away less efficient methods of production, giving way to more advanced processes that work to increase the rate of profit. Hence, in the period of upswing, boom periods are longer, with shorter recessions, very often giving way to even greater expansion when they have passed.

In a period of downswing, however, we see the opposite effect. Booms are shorter and more feeble, while periods of recession and stagnation and deeper and longer.

Economic transitions

The question which now arises is the following: what causes the passage from one phase of development to another? Clearly it cannot be the business cycle as such—that operates in all periods—although the transition will often be announced by a recession or a boom.

The transition from a period of upswing to downswing is rooted in the accumulation process itself. As capital accumulation proceeds, and the mass of capital grows in relation to the labour which set it in motion, the rate of profit will tend to fall. This is because the sole source of surplus value, and ultimately of all profit, is the living labour of the working class, and this living labour declines in relation to the mass of capital it is called on to expand. Of course, this tendency can be, and is, overcome through an increase in the productivity of labour. However, within a given regime or system of production there will come a point where no further increases in productivity can be obtained, or they are so small that they cannot counter the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. At this point, the curve of capitalist development begins to turn down.

This analysis points to the conditions necessary to secure an upswing. It can only take place with the development of new methods that change the nature of the production process itself. In other words, such methods mark not a quantitative but a qualitative change. There are a number of examples that come to mind: in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the so-called second industrial revolution, which saw the birth of mass industrial methods, eventually gave rise to a new upswing that commenced in the mid-1890s. Earlier in that century, the use of steam power and the development of the railways opened up vast new markets, resulting in an upswing which ended the depressed conditions of the 1830s and 1840s and created the conditions for the Victorian-era boom in the middle of the century.

The most striking example of the transition from a period of downswing to upswing in the capitalist curve is the post World War II boom. This was the outcome of the complete reconstruction of the economy of Europe, and the spread of the more advanced assembly-line methods of production developed in the United States in the first two decades of the century. These methods, which had the potential to bring about a capitalist expansion because of the enormous increase in surplus value they produced, could not be applied in the Europe of the mid-century. The market was too constricted, cut across by national boundaries and borders, protectionist tariffs and cartels that restricted production.

Thus, the key to post-war reconstruction was not just the $13 billion of capital pumped in from the United States under the Marshall Plan. It was the reconstruction of the market that went with it—the progressive abolition of the internal barriers within Europe, enabling the development of the new, more productive methods. The result was the longest upswing in the history of global capitalism.

But this “golden age” did not resolve the contradictions of the capitalist economy, and they inevitably erupted to the surface once again in the form of falling profit rates, a deep recession and financial turmoil. The beginning of the 1970s marked a new period of downswing in the curve of capitalist development.

This downswing has formed the framework for the vast and on-going re-organisation and restructuring of the global capitalist economy over the past quarter-century. Whole sections of industry in the major capitalist countries have been closed down, new computer-based technologies introduced and, above all, new systems of production and information transfer developed, making possible the globalisation of the production process itself.

Combined with these transformations has been an unending offensive against the social position of the mass of working people: the steady reduction of real wages, the destruction of full-time jobs and their replacement with part-time or casual employment, cuts in health, education and social services, together with the privatisation of what were once public facilities.

In the former colonial countries, the past two decades have seen the wiping out of the previous programs of national economic development and the imposition of structural adjustment programs enforced by the International Monetary Fund on behalf of the major global banks, creating the conditions where today, for example, sub-Saharan Africa hands over more in debt repayments than the combined spending on health and education.

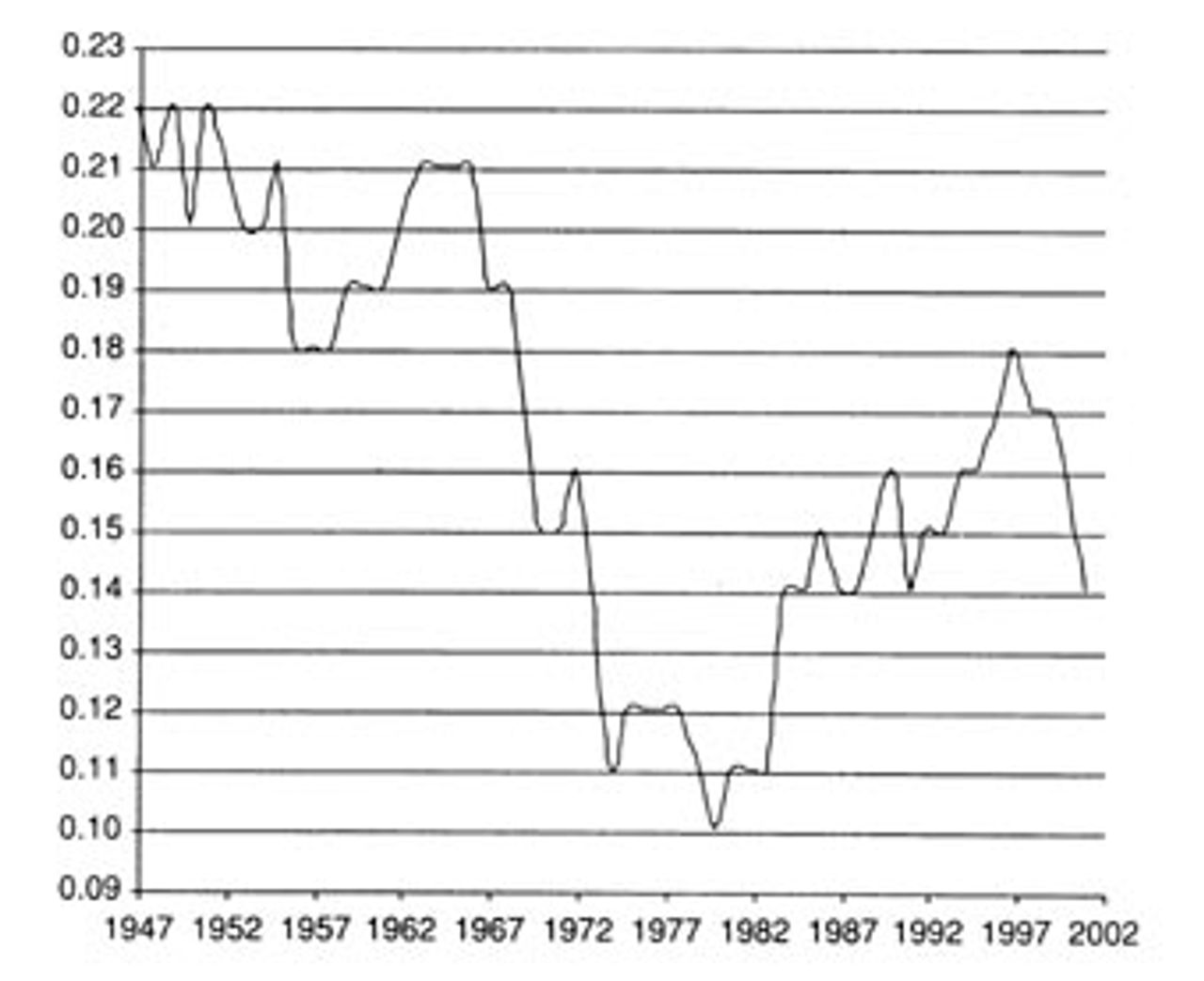

All of these measures have been aimed at increasing the mass of profit. But they have failed to produce a new capitalist upswing. Let us examine the key measure—the rate of profit. From 1950 to the mid-1970s, the rate of profit in the US is estimated to have declined from 22 percent to about 12 percent—a drop of almost 50 percent. Since then it has recovered only about one-third of its previous decline, despite the fact that real wages have probably fallen by about 10 percent. After rising briefly in the mid-1990s, it has dropped away sharply again from 1997 onwards.

The profit rate in the post-war US economy

(Reproduced from Fred Moseley, “Marxian Crisis Theory and the Post-war US Economy” in Anti-Capitalism, a Marxist Introduction, Alfredo Saad-Filho, ed., p. 212)

Capitalism in the 1990s

Let us step back and take a wider view of world capitalism during the 1990s. The collapse of the Soviet Union was greeted with a chorus of triumphalism by the spokesmen of the capitalist class. How has world capitalism fared over this past decade and a half?

There is no ambiguity: its position has dramatically worsened. In the US, capacity utilisation in industry is around 72 percent; investment shows no sign of increasing, and the economy is only being sustained by what amounts to a zero interest rate policy on behalf of the Federal Reserve Board. There are fears of financial collapses; the federal budget deficit is $300 billion and rising; the majority of state governments are on the edge of bankruptcy. The balance of payments deficit is over $500 billion and threatening to increase still further. In order to finance its payments gap, the US has to suck in $1 million every minute from the rest of the world, all day, every day.

Japan is now entering its second decade of stagnation as questions continue to be raised over the viability of its major banks and financial institutions. In Europe, economic growth has virtually come to a halt, with Germany either on the edge of, or in, a recession.

Lest I be accused of exaggerating the situation, allow me to cite an assessment of the world economy by one of the most well-known global economists for the finance firm Morgan Stanley. He writes: “Global imbalances have never been more acute. Global deflation has never been a greater risk. And there has been an extraordinary confluence of asset bubbles—from Japan to America. Moreover, the Authorities have never been so lacking in conventional weapons to meet these challenges.”

Policymakers, he continues, are focused on this situation but “their confident public statements belie the deep sense of concern they express in private. The truth is there are no proven remedies to the multiple perils of external imbalances, deflationary risks, and post-bubble shocks.” Moreover the discussion in leading financial policy circles about the use of “non-traditional policies” is “emblematic of how desperate matters have become” and “reflects a mindset that hasn’t been seen since the 1930s,” reflecting in turn “perils in the global economy that haven’t been seen in the modern era” (Stephen Roach, An Historic Moment, June 23, 2003).

In its latest report on the world economy, the Bank for International Settlements notes that despite the “high degree of policy stimulus being applied in large parts of the world” hopes regarding the global economy have repeatedly been disappointed, leading to attention being focused on the possibility that “more deep-seated forces might be at work.”

One would have to conclude, on the basis of these assessments, that the capitalist prospectus of the early 1990s for a new era of peace and global prosperity was somewhat oversold.

These phenomena—deepening deflation, persistent stagnation, financial speculation and outright looting, industrial overcapacity, massive economic imbalances—are all different symptoms of an acute crisis in the capitalist accumulation process itself. In other words, the downswing in the curve of capitalist development that began some 30 years ago, has, despite all the strenuous efforts to reverse it, become steeper, signifying a crisis at the very heart of the capitalist economy. Moreover, this crisis is concentrated in the most powerful economy of all, the United States. This is the driving force behind the eruption of American imperialism.

We should recall Trotsky’s prophetic words, written more than 70 years ago as the US was beginning its global ascendancy. A crisis in America, he explained, would not bring about a retreat. “Just the contrary is the case. In the period of crisis the hegemony of the United States will operate more completely, more openly, and more ruthlessly than in the period of boom. The United States will seek to overcome and extricate herself from her difficulties and maladies primarily at the expense of Europe, regardless of whether this occurs in Asia, Canada, South America, Australia, or Europe itself, or whether it takes place peacefully or through war” (Trotsky, The Third International After Lenin p. 8).

The political economy of rent

In order to reveal more clearly the forces driving US imperialism and its plans for global domination, we need to further consider, if only in outline, some fundamental relationships within the capitalist economy.

The sole source of surplus value—the basis of the accumulation of capital—is the living labour of the international working class. This surplus is distributed among the different forms of property as industrial profit, interest and rent. When we say “distributed” we do not mean that this is a peaceful affair. It takes place through a relentless struggle for markets and resources.

It is within this process that rent plays an important role. Rent refers not just to the accumulation of wealth through the ownership of land. It is, more generally, the revenue that can be extracted through monopoly ownership of a particular resource, or by means of political power.

Revenue accruing from rent does not represent the creation of wealth. Rather, it is a form of appropriation of the already created surplus value by right of ownership or by political means. It is a deduction from the surplus value that is available to capital as a whole. There is, therefore, a potential antagonism between the rent appropriator and capital.

During an upswing in the curve of capitalist development, when profits are rising or have attained fairly high levels, the existence of rents does not assume great importance. But the situation changes dramatically when the capitalist curve turns down and profit rates begin to fall. Then rents become intolerable for the dominant sections of industrial and finance capital and they raise the battle cry “freedom of the market” as they strive to divert the revenue stream accruing to the rent appropriator.

The political economy of rent has immediate relevance to the current war and the striving by US imperialism to secure Iraq’s resources. The war’s supporters dismissed the claim that it was being launched to secure oil by pointing out that US interests could easily purchase Iraqi oil on the world market. Furthermore, they claimed, if oil were the motivation, the US should have pushed for the lifting of sanctions and the resumption of Iraqi production, thereby increasing the supply on world markets and lowering the price—to the benefit of oil purchasers.

All such arguments are aimed at covering over the fact that the underlying economic impetus is not oil as such, but the massive differential rents that arise in the oil industry due to varying natural conditions. In other words, the conquest of Iraq has not been undertaken so much to pump gas into American SUVs, but to pump surplus value and profits into US corporations.

We can obtain a rough guide as to what is available by considering the economics of Iraqi oil production. The proven Iraqi oil reserves are around 112 billion barrels. It is estimated, however, that total reserves are probably well over 200 billion barrels and may even be as much as 400 billion. What makes these reserves so attractive is the low cost of their extraction, and the enormous differential rent to which that gives rise.

According to the US Department of Energy “Iraq’s oil production costs are amongst the lowest in the world, making it a highly attractive oil prospect.” It is estimated that a barrel of Iraqi oil can be produced for less than $1.50 and possibly even as little as $1. This compares to $5 in other low cost areas, such as Malaysia and Oman, and between $6 and $8 a barrel in Mexico and Russia. Production costs in the North Sea run between $12 and $16 a barrel, while in the US fields they can reach as much as $20.

If one assumes an oil price in real terms of around $25 per barrel then the total value of Iraqi reserves, after deducting costs of production, is around $3.1 trillion. (See James A. Paul Oil in Iraq: the heart of the crisis, Global Policy Forum December 2002)

In the early 1970s, a number of oil producing countries, including Iraq, nationalised their oil industries. This meant that a large portion of the available rents was placed at the disposal of the national bourgeois regimes of these countries. That situation has become ever more intolerable for the major imperialist powers.

Over the past decade and a half there has been a wave of privatisation around the world, including in the former colonial countries, as part of the “restructuring” programs dictated by the IMF. So far oil has not met this fate. But it is a key target. In the final days of the Clinton administration, for example, a congressional hearing was called on “OPEC’s Policies: A Threat to the US Economy.” Its chairman denounced the Clinton administration for being “remarkably passive in the face of OPEC’s continued assault on our free market system and our anti-trust norms” (See George Caffentzis, In What Sense ‘No Blood for Oil’).

Consideration of these economic issues brings into clearer focus what exactly is meant by “regime change.” It involves much more than the removal of particular individuals, many of them one-time allies or assets of the US, who have now come into conflict with it. Regime change signifies a complete economic restructuring.

Richard Haass, until very recently the director of Policy Planning in the US State Department, set it out clearly in his book Intervention. Force alone and simply targeting individuals, he insisted, was not enough and would not bring about specific political change. “The only way to increase the likelihood of such change is through highly intrusive forms of intervention, such as nation-building, which involves first eliminating all opposition and then engaging in an occupation that allows for substantial engineering of another society” (cited in John Bellamy Foster, “Imperial America and War” in Monthly Review May 2003).

In recent speeches, Haass has explained that in the twenty-first century “the principal aim of American foreign policy is to integrate other countries and organisations into arrangements that will sustain a world consistent with US interests and values”. What he terms “closed economic systems,” particularly in the Middle East, “pose a danger” and this is why Bush has proposed the establishment of a US-Middle East free trade area within a decade.

What this scorched earth policy means can be seen in the case of Iraq, where US corporations have lined up to receive profit input from the sale of oil. They include: Halliburton, a two-year contract with a maximum value of $7 billion to fight oil fires and also to pump and distribute Iraqi oil; Kellogg, Brown and Root, a $71 million contract to repair and operate oil wells; Bechtel, an initial contract of $34.6 million, but with the potential for up to $680 million to rebuild power generation and water supply systems; MCI WorldCom, a $30 million contract to build a wireless network in Iraq; Stevedoring Services of America, a year-long contract worth $4.8 million to manage and repair Iraqi ports, including the deep-water port of Umm Qasr; ABT Associates, an initial $10 million contract to provide support for health services; Creative Associates International, a $1 million contract initially with the possibility of an increase up to $62.6 million to address the “immediate educational needs” of Iraq’s primary and secondary schools; Dyncorp, a multi-million contract, possibly worth as much as $50 million, to advise the Iraqi government on setting up effective law enforcement, judicial and correctional agencies; International Resource Group, an initial $7.18 million contract to assist with contingency planning for emergency and near-term rehabilitation; plus a host of small contracts and other firms that stand to benefit from sub-contracts let out by major contractors. (See The Corporate Invasion of Iraq: Profile of US Corporations Awarded Contracts in US/British-Occupied Iraq prepared by US Labor Against the War)

Global reconstruction

It is not just a matter of oil rents. What is taking place in Iraq is a particularly violent expression of a global process—the tearing down of all impediments to the global reach and domination of US capital. The “restructuring” policies commenced in the 1980s have seen the transfer of billions of dollars into the coffers of the banks from some of the most impoverished nations. Through privatisation, basic amenities—water, electricity, health services and education—have been opened up to the extraction of profit.

Nothing must be allowed to stand in the way of this project of global reconstruction— and certainly not barriers erected by national governments. As a number of its ideological supporters have commented, the task of the US is to create the kind of international political and economic order led by Britain in the nineteenth century.

The essence of that order, according to a paper entitled In Defense of Empires by Deepak Lal, published by the American Enterprise Institute, was that it guaranteed international, as opposed to national, property rights. The collapse of this order in World War I, he claims, produced the disorder of the 1920s and 1930s, followed by the post-war period in which the new nation-states asserted their national sovereignty against international property rights. Now, according to Lal, this situation has finally been overcome with the undisputed emergence of the United States as the world hegemon.

The requirements of international, and more particularly US, capital for global reach and global penetration into every corner of the world, are given political expression in the new doctrine insisting that national sovereignty is limited and conditional.

According to Richard Haass, in a speech delivered last January as the US was preparing for the invasion of Iraq, one of the most significant developments of the recent period is that “sovereignty is not a blank cheque.” Recalling the words of Theodore Roosevelt, he continued: “Rather, sovereign status is contingent on the fulfillment by each state of certain fundamental obligations, both to its own citizens and to the international community. When a regime fails to live up to these responsibilities or abuses its prerogatives it risks forfeiting its sovereign privileges—including, in extreme cases, its immunity for armed intervention. ... Non-intervention is no longer sacrosanct ... ” (Richard Haass Sovereignty: Existing Rights, Evolving Responsibilities, January 14, 2003).

Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer echoed these remarks when he announced the Howard government’s decision to send a military force to intervene in the Solomons. Multilateralism, he declared in his address to the National Press Club, was increasingly a synonym for an “ineffective and unfocused policy”. Australia was prepared to join “coalitions of the willing” to bring focus to urgent security and other challenges. “Sovereignty in our view is not absolute. Acting for the benefit of humanity is more important.”

But who decides that a nation has forfeited its rights to sovereignty and that “coalitions of the willing” must act in the interests of humanity? Clearly the dominant imperialist powers, with the US giving the go ahead to those within its orbit.

The contradiction between world economy and the nation state

The immediate impetus for the drive to global domination by the US is rooted in the crisis of capitalist accumulation, expressed in the persistent downward pressure on the rate of profit and the failure of the most strenuous efforts over the past 25 years to overcome it. But it is more than this. At the most fundamental level, the eruption of US imperialism represents a desperate attempt to overcome, albeit in a reactionary manner, the central contradiction that has bedeviled the capitalist system for the best part of the last century.

The US came to economic and political ascendancy as World War I exploded. The war, as Trotsky analysed, was rooted in the contradiction between the development of the productive forces on a global scale and the division of the world among competing great powers. Each of these powers sought to resolve the contradiction by establishing its own ascendancy, thereby coming into collision with its rivals.

The Russian Revolution, conceived of and carried forward as the first step in the international socialist revolution, was the first attempt of a detachment of the working class to resolve the contradiction between world economy and the outmoded nation-state framework on a progressive basis. Ultimately, the forces of capitalism proved too strong and the working class, as a result of a tragic combination of missed opportunities and outright betrayals, was unable to carry this program forward.

But the historical problem that had erupted with such volcanic force—the necessity to reorganise the globally developed productive forces of mankind on a new and higher foundation, to free them from the destructive fetters of private property and the nation-state system—did not disappear. It was able to be suppressed for a period. But the very development of capitalist production itself ensured that it would come to the surface once again, even more explosively than in the past.

The US conquest of Iraq must be placed within this historical and political context. The drive for global domination represents the attempt by American imperialism to resolve the central contradiction of world capitalism by creating a kind of global American empire, operating according to the rules of the “free market” interpreted in accordance with the economic needs and interests of US capital, and policed by its military and the military forces of its allies.

This deranged vision of global order was set out by Bush in his address to West Point graduates on June 1, 2002. The US, he said, now had the best chance since the rise of the nation-state in the seventeenth century to “build a world where great powers compete in peace instead of prepare for war.” Competition between great nations was inevitable, but war was not. That was because “America has, and intends to keep, military strengths beyond challenge thereby making the destabilising arms races of other eras pointless and limiting rivalries to trade and other pursuits of peace.”

This proposal to reorganise the world is even more reactionary than when it was first advanced in 1914. The US push for global domination, driven on as it is by the crisis in the very heart of the profit system, cannot bring peace, much less prosperity, but only deepening attacks on the world’s people, enforced by military and dictatorial forms of rule.

What then is the way forward? How to fight the drive for global domination by US imperialism and all the catastrophes that flow from it? That is the problem history has presented us with.

History, however, as Marx noted, never presents a problem without at the same time providing the material conditions for its resolution.

The globalisation of production, to which the eruption of US imperialism is a predatory and reactionary response, has, at the same time, created the conditions for an historically progressive response through the unification of the mass of ordinary working people on an international scale never before possible, and only dreamed of in the past.

This was the objective significance of the demonstrations that erupted worldwide before the invasion of Iraq—demonstrations in which the participants correctly saw themselves as part of a global movement, and drew strength from that understanding. The mass mobilisations revealed that it is not only the productive forces that have been globalised, but the political actions of struggling humanity as well.

This new situation was the subject of a comment in the New York Times that there seemed to be two powers in the world—the United States and world public opinion. Or, as a recent comment in the Financial Times put it, Karl Marx may have the last laugh after all because global capitalism is “giving rise to pressures that may eventually globalise politics.”

Lessons of global antiwar protests

But five months on we must make an assessment of what took place. The movement showed the vast potential that exists, but also the problems that have to be overcome for that potential to be realised. These problems essentially boil down to one: the crisis of political perspective.

What the demonstrations showed was the absence of a clearly worked out program and perspective. To the extent that one existed it was a sentiment that if enough pressure could be brought to bear then somehow war could be prevented. In that regard, the demonstrations were a kind of giant experiment to test out the validity of protest politics.

It was as if History had said: Despite the lessons of the past, you believe, not through any fault of your own, that mass pressure can decisively influence the ruling powers. Very well, I will organise a giant test for you in the form of the biggest global protests ever seen. Not only will I do that, I will also arrange it so that the United Nations refuses to give its vote for this war—the validity of this organisation will be tested as well—and we shall see if this can prevent the invasion taking place. But History would have also said: In return for this I only ask from you one thing: that at the conclusion of this experiment, you draw the necessary lessons from its failure.

What are these lessons? That the mass movement requires a coherent program and perspective aimed not at pressuring the ruling classes but at the conquest of political power.

There are no easy answers in the development of this perspective. It is not a matter of hitting upon some new or clever slogan or of organising still more powerful protests. The mass movement must be armed with the understanding that only with the conquest of political power by the international working class can the difficult and complex problems confronting humanity be overcome. That requires, above all, an assimilation of the history of the twentieth century. This task forms the basis of all the work of the World Socialist Web Site.

In order to clarify these conclusions, I would like to examine a recent article by George Monbiot, one of the leading British writers of what could be called the global justice movement. Writing in the Guardian of June 17, Monbiot correctly points out that while economic globalisation sweeps all before it, it also creates as well as destroys, extending to the world’s people unprecedented opportunities for their mobilisation. This was precisely the point being made by the WSWS when Monbiot and others were denouncing “globalisation” as the enemy. Now, he writes, business, by expanding its empire, has created the conditions where the world’s people can coordinate their challenge to it. This means that we may “be approaching a revolutionary moment.”

The problem, however, is that the movement has no program and this he correctly identifies as its crucial weakness. Our task, he continues, is “not to overthrow globalisation, but to capture it, and use it as a vehicle for humanity’s first global democratic revolution.”

While one might be able to agree with these broad sentiments, the problems arise when we consider Monbiot’s proposals for the content of this global democratic revolution.

He proposes two key measures. The first is the scrapping of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank and their replacement with a body rather like that proposed by Keynes at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944, whose purpose was to prevent the formation of excessive trade surpluses and deficits. The second is the scrapping of the UN Security Council and the vesting of its powers in a reformed UN general assembly where nations would have votes according to the size of their population and their positions on a “global democracy index.”

Viewing these proposals for “global democratic revolution” one can only say: the mountain has laboured and brought forth ... a mouse.

Monbiot is correct to insist that new democratic forms of global governance have to be established. But if democracy is to have any real meaning then it must signify that the giant transnational corporations, banks and global financial institutions are taken out of private hands and brought under public ownership, subject to democratic control. In short, genuine democracy—the rule of the people—can only be obtained by ending the rule of capital. They cannot co-exist.

Margaret Thatcher understood this very well. There was, she said, no such thing as “society” and summed up the operation of the “free market” in the phrase “there is no alternative”. She was right.

But that is precisely the point: if there is no alternative, then there is no democracy. Democracy involves the making of choices between alternatives, in making decisions and then perhaps changing them, or refining and developing them. If there is no alternative then there is dictatorship, the dictatorship of capital and the subordination of the interests, needs, aspirations of the world’s people to its unending drive for profit.

In conclusion, let me ask you to consider how different the situation would be today had the mass movement that erupted in February, having assimilated and worked over the bitter experiences of the twentieth century and drawn the necessary political lessons, been guided by the understanding that the key to the struggle against imperialism and war was the development of the international socialist revolution. The present political arena would be vastly different.

As it is, the imperialist powers seem to have gotten away with a monstrous crime, and there is something of a political lull. That will pass. New struggles will develop. But the key question remains: on what program and perspective? They will go forward to the extent that they are grounded on the conception that the task is not to pressure this or that government, much less the UN, or that it is possible to revive the parties and organisations which once commanded mass support, but to develop the international socialist movement of the working class of the twenty-first century, grounded on all the lessons of the twentieth.

The aim of the World Socialist Web Site is to provide the necessary orientation to this movement and construct the international revolutionary party to lead it. We envisage this conference as a step towards that goal.

Concluded