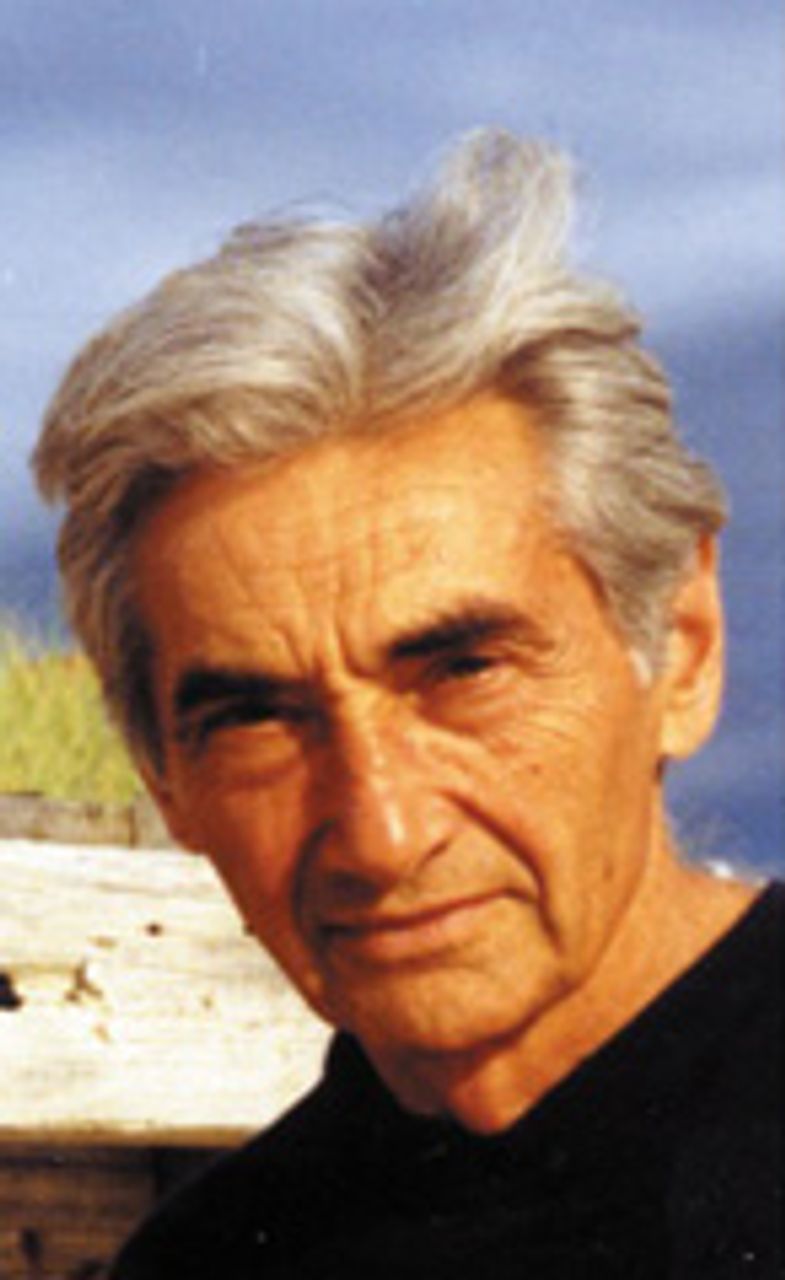

Howard Zinn, historian, activist, and author of A People’s History of the United States, died on January 28 at the age of 87.

Howard Zinn

Howard ZinnBorn in Brooklyn in 1922 to Jewish immigrant factory-worker parents, his father from Austria-Hungary and his mother from Siberia, Zinn came of age during the Great Depression in a sprawling working class neighborhood. The influence of socialism and the presence of the Communist Party were particularly pronounced in this time and place; Zinn recalled attending a CP rally as a youth where he was clubbed by a policeman. Books were few until his father purchased him a Charles Dickens compilation.

Zinn served in WWII as a bomber pilot. He was deeply troubled by his participation in a needless mission at the war’s end during which his plane dumped napalm—in its first-ever military use—on a target in France, killing both German soldiers and perhaps 1,000 French civilians. After the war he went back to the area of France he had bombed and dealt with the experience in his book, The Politics of History. Zinn was, by all accounts, humane.

His outspoken support of student civil rights activists and the Student Non Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) led to Zinn’s dismissal from his first academic job, at the all-black women’s school, Spelman, in Georgia, in 1963. He then secured a position at Boston University held until his retirement in 1988.

Zinn was also a notable Vietnam War protester. In 1968 he visited Hanoi with the Reverend Daniel Berrigan and secured the release of three US prisoners of war, and in 1971 Daniel Ellsberg gave Zinn a copy of what came to be known as “the Pentagon Papers.” Zinn would edit and publish it with his longtime collaborator, Noam Chomsky.

Zinn’s work as an historian spanned five decades and resulted in the publication of numerous books, articles and essays, but it was his A People’s History of the United States, published in 1980, that brought him to a place of relative prominence. The book has sold more than 2 million copies in multiple editions. A television documentary based on it, “The People Speak,” was broadcast in 2009, and featured readings and performances by Matt Damon, Morgan Freeman, Bob Dylan, Marisa Tomei, Bruce Springsteen and Danny Glover, among others.

Given the book’s influence, any evaluation of Zinn requires serious consideration of his work as an historian.

A People’s History is a much-loved book for good reason. In accessible, direct language, Zinn introduced hundreds of thousands of readers to aspects of US history written out of what was, in all but name, the official narrative, with its essentially uncritical presentation of the US political and economic elite.

Zinn relentlessly exposed the self-interest and savagery of “the Establishment,” as he called it, while at the same time bringing to life the hidden political and social struggles of oppressed groups in US history—workers, the poor, Native Americans, African Americans, women and immigrants. Zinn did not hide his sympathies for the oppressed in history. “[I]n such a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners,” he wrote, “it is the job of thinking people, as Albert Camus suggested, not to be on the side of the executioners.”

A People’s History grew out of, and in turn contributed to, a growing skepticism of the democratic pretensions of the American ruling class—particularly among the youth. These characteristics of Zinn’s work earned him the hatred of those who wish to see college and high school curriculum more tightly controlled; after Zinn’s death, right-wing ex-radicals David Horowitz and Ronald Radosh penned columns attacking him for exposing truths about the US government to a mass audience. Indeed, no one who has read A People’s History could in honesty endorse President Obama’s recent claim that Washington does “not seek to occupy other nations” and is heir “to a noble struggle for freedom,” or the right wing’s absurd mantra that the US military is “the greatest force for good in world history.”

The book’s 23 short chapters begin with Christopher Columbus’ landing in the Americas in 1492 and the brutal slaughter of Native Americans. What follows is a chronological account of American history, focusing in particular on different social and political struggles, with Zinn providing a varying degree of historical context depending on the period. This is, in the end, a limited method, a problem that we shall address presently. But the contributions of Zinn’s essentially empirical approach—the inversion of the official narrative through the presentation of hidden or alternative facts—has much to teach.

This empirical strength runs through most of the book, but there are chapters where it combines with greater attention to context. His treatment of WWII, “A People’s War,” is one of his better. As a rare honest accounting of what has been uncritically presented by most liberal and radical historians as a “war against fascism,” it merits attention.

The chapter lists Washington’s many imperialist interventions over the preceding decades, and points out its indifference to fascist Italy’s rape of Ethiopia in 1935 and Germany’s and Italy’s intervention on behalf of the fascist forces of Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War. This was “the logical policy of a government whose main interest was not stopping Fascism but advancing” its own imperialist interests. “For those interests, in the thirties, an anti-Soviet policy seemed best,” Zinn concludes. “Later, when Japan and Germany threatened US world interests, a pro-Soviet, anti-Nazi policy became preferable.”

This policy could be dressed up in anti-fascist guise, but “[b]ehind the headlines in battles and bombings, American diplomats and businessmen worked hard to make sure that when the war ended, American economic power would be second to none [and] business would penetrate areas that up to this time had been dominated by England.”

At home, the hypocrisy of a “war against fascism” was not lost on African Americans, who remained subject to job and housing discrimination in the North and Jim Crow segregation, disenfranchisement and terror in the South, nor on Japanese Americans, 110,000 of whom were rounded up—many of these second and third generation citizens—and placed in internment camps on the order of President Franklin Roosevelt.

Still more hidden from popular memory was the immense struggle of the working class during the war. “In spite of no-strike pledges of the AFL and CIO there were 14,000 strikes, involving 6,770,000 workers, more than in any comparable period in American history,” Zinn wrote. “In 1944 alone, a million workers were on strike, in the mines, in the steel mills, in the auto and transportation equipment industries. When the war ended, the strikes continued in record numbers—3 million on strike in the first half of 1946.”

In spite of the strike wave, “there was little organized opposition from any source,” he notes. “The Communist Party was enthusiastically in support... Only one organized socialist group opposed the war unequivocally. This was the Socialist Workers Party. In Minneapolis in 1943, eighteen members of the party were convicted for violating the Smith Act, which made it a crime to join any group that advocated ‘the overthrow of the government.’“ The Socialist Workers Party was the Trotskyist movement in the US at that time.

Zinn writes movingly in the chapter of the savage bombings by the US and Britain of German and Japanese population centers; doubtless his own experience as a bomber pilot in Europe breathed feeling into these pages. Zinn also exposes the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which remain enshrined in the official mythology as necessary military acts. In fact, the decision that incinerated and poisoned hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians was made with an eye cast toward the postwar order. By forcing a rapid Japanese surrender before the Red Army moved further into the Korean peninsula, the Truman administration hoped to assert US dominance in East Asia.

It is to Zinn’s credit that he concludes the chapter with a discussion of the early Cold War and the Red Scare, which were prepared by US victory in “the Good War.” After the war, US liberalism quickly turned on its radical allies grouped around the Communist Party. The Truman administration “established a climate of fear—a hysteria about Communism—which would steeply escalate the military budget and stimulate the economy with war-related orders.” What was needed was a consensus that “could best be created by a liberal Democratic president, whose aggressive policy abroad would be supported by conservatives, and whose welfare programs at home … would be attractive to liberals.”

Zinn’s chapter on Vietnam, “The Impossible Victory,” merits reading. In only 10 pages, he offers a good look at the history of Vietnam’s long struggle for independence against France, Japan in WWII, then France again, and finally the US. With both statistics and vivid illustrations, he reveals the barbarity of US imperialism. “By the end of the war, seven million tons of bombs had been dropped” on Southeast Asia, “more than twice the amount” used in both Europe and Asia in WWII. Zinn’s presentation of the My Lai massacre, napalm, the US assassination program called Operation Phoenix, and other cruelties are damning of Washington’s claim that the US military was there to defend the Vietnamese people. The second half of the chapter focuses on the growing popular opposition to the Vietnam War within the US on the campuses, among working people, and in the army itself.

It is not possible here to consider all the book’s chapters, but in general, those that cover the century lasting from the end of Reconstruction in the post-Civil War to the end of the Vietnam War are strong and empirically rich.

Zinn writes effectively on WWI (“War is the Health of the State”), describing vividly the insanity of trench warfare, and detailing the mass opposition to US entry and the strenuous efforts to overcome this. His chapter on the US embrace of imperialism in the Spanish-American War correctly spots the underlying drive as a struggle for markets by US capitalism. Zinn consistently turns up useful quotes to illustrate his points, here presenting Mark Twain’s comments on the US effort to subjugate the Philippines after Spain’s defeat: “We have pacified some thousands of the islanders and buried them; destroyed their fields; burned their villages, and turned their widows and orphans out-of-doors. And so, by these Providences of God—and the phrase is the government’s, not mine—we are a World Power.”

Zinn correctly places socialism at the center of the Progressive Era, circa 1900 until 1917, entitling this chapter “The Socialist Challenge.” Progressivism “seemed to understand it was fending off socialism,” as Zinn puts it. The chapter includes brief accounts of the great garment workers’ strike of New York City in 1909—and the Triangle garment factory fire in its aftermath—the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) Lawrence, Massachusetts textile strike, and the Ludlow massacre of coal miners in Colorado in 1914.

Two chapters on workers’ and farmers’ struggles in the 19th century, “Robber Barons and Rebels” and “The Other Civil War,” demonstrate with examples the rich history of egalitarianism that remains the patrimony of today’s working class. Zinn’s selection of an 1890 quote from the Kansas populist Mary Ellen Lease seems timely: “Wall Street owns the country. It is no longer a country of the people, by the people, and for the people, but a government of Wall Street, by Wall Street, and for Wall Street... The people are at bay, let the bloodhounds of money who have dogged us thus far beware.”

Yet while it is helpful in bringing to light facts written out of standard textbooks, Zinn’s work can only serve as a beginning to understanding US history. There is an unmistakable anachronistic, even a-historical, thread in A People’s History. If it has a theme, it is an endless duel between “resistance” and “control,” two of Zinn’s preferred words. Populating his historical stage are, on the one side, a virtually unbroken line of “Establishment” villains who exercise this control and, on the other, benighted groups who often struck out against their plight. The names and dates change; the story does not.

Complexity and contradiction does not rest comfortably in such a schema. The limitations of this approach are most evident in Zinn’s treatment of the American Revolution and the US Civil War, which he presents as instances of the elite beguiling the population in order to strengthen its control.

“Around 1776, certain important people in the English colonies made a discovery that would prove enormously useful for the next two hundred years,” Zinn opens the first of his two chapters on the American Revolution. “They found that by creating a nation, a symbol, a legal unity called the United States, they could take over land, profits, and political power from favorites of the British Empire… They created the most effective system of national control devised in modern times.”

Zinn presents the Civil War in similar terms. Only a slave rebellion or a full-scale war could end slavery, he wrote: “If a rebellion, it might get out of hand, and turn its ferocity beyond slavery to the most successful system of capitalist enrichment in the world. If a war, those who made the war would organize its consequences.” (In fact, the Civil War became both a full-scale war and a slave rebellion.) “With slavery abolished by order of government,” Zinn asserted, “its end could be orchestrated so as to set limits to emancipation,” a task that fell to none other than Abraham Lincoln, who in Zinn’s presentation, was merely a shrewd political operative who “combined perfectly the needs of business, the new Republican party, and the rhetoric of humanitarianism.”

This deeply subjective rendering of the two most progressive events in US history calls to mind Frederick Engels’ comments on “old materialist” philosophy, an approach that could not answer the question of what historical forces lay behind the motives of individuals and groups in history, the “historical forces which transform themselves into these motives in the brains of the actors.”

“The old materialism never put this question to itself,” Engels responds. “Its conception of history, in so far as it has one at all, is therefore essentially pragmatic; it divides men who act in history into noble and ignoble and then finds that as a rule the noble are defrauded and the ignoble are victorious.” Such, in short, was Howard Zinn’s operating thesis.

In his search for the origins of motives in history, Zinn at times lapsed into moralizing. He denied the characterization—writing on the American Revolution, Zinn said he would not “lay impossible moral burdens on that time.” But this is precisely what he did, even in the case of the more progressive revolutionists.

After discussing the enormous circulation of Tom Paine’s writings in the colonies, Zinn concludes that Paine was too linked to the colonial elite. “[H]e was not for the crowd action of lower-class people,” Zinn asserts, because Paine had “become an associate of one of the wealthiest men in Pennsylvania, Robert Morris, and a supporter of Morris’s creation, the Bank of North America.” Paine “lent himself perfectly to the myth of the revolution—that it was on behalf of a united people,” is Zinn’s verdict on one of the great revolutionists of the epoch. As for Thomas Jefferson, Zinn cited disapprovingly on two occasions that he owned slaves.

Thirty years ago, criticism of the mythology surrounding Lincoln or a Jefferson was perhaps useful. Such lines appear more wearisome today after decades of moralistic attacks by well-heeled scholars like Lerone Bennett; if an historian does nothing else, he or she should concede that their subjects lived in a different time. More importantly, in the cases of the Civil War and the American Revolution, Zinn’s anachronism distorted historical reality, minimizing the progressive character of those struggles.

It is worthwhile to note the work of historian Bernard Bailyn and Gordon Wood. Bailyn, in his Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, demonstrated, through analysis of scores of commonly read political tracts in the colonies, that the thinking of the revolutionists was radical and progressive and ultimately rooted in a century of Enlightenment thought.

Wood, in The Radicalism of the American Revolution (1992), seems to address himself to Zinn’s sort of argument that the war for independence was “hardly a revolution at all.” It was, Wood writes, “one of the greatest revolutions the world has known” and “the most radical and far-reaching event in American history.” Wood concedes that the Founding Fathers, having recognized the social forces unleashed by the revolution, sought to contain democracy through the Constitution. But Wood shows that this effort did not undo the radicalism of the revolution, which had been broadly transfused into social consciousness.

The American Revolution, like the French Revolution it helped to inspire, marked a great historical advance. It proclaimed in stirring language basic democratic rights, and laid these out in the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights. It repudiated the divine right of king’s to rule, and threw off restraints on economic development designed to benefit the crown.

That the revolution raised up contradictions that it could not yet resolve—the most obvious being its declarations of liberty while maintaining slavery—does not erase these achievements. The new ruling class, which Zinn tended to treat as a monolithic whole, was in fact deeply divided over slavery and economic policy toward Great Britain. The Civil War would resolve these conflicts and put in place new ones, bringing to the fore the struggle between the working and capitalist classes that has been the axis of US history ever since.

Like other great progressive causes, the American Revolution has in a certain sense transcended the limitations imposed upon it by its time by inspiring and animating the progressive struggles that followed—including the struggle against slavery. To cite an example, Zinn himself noted that the Vietnamese anti-imperialists modeled their own declaration of independence on that written by Jefferson.

It must be stated clearly that Zinn’s method had little to do with Marxism, which understands that history advances through the struggle of contending social classes, a struggle rooted in the social relations of economic production. While this does not by itself negate the value of a scholarly work, Zinn’s limitations as an historian require some attention be paid to his political views, which grew out of the traditions of American radicalism. The two were, as he himself declared, mutually constitutive.

Zinn drew his material not from his own research, but from a growing body of “revisionist” scholarship during a period when radicals made inroads on US college campuses. Beginning in the late 1960s, new academic pursuits emerged: critical revisionist studies of political, diplomatic and labor history, and new fields such as African American history, women’s history, Native American history, and many more. This approach—the criticism of establishment history and the presentation of the social history of the oppressed who had left behind little or no written record—was fresh and yielded, at least in its earlier stages, significant results.

Later, beginning in the 1980s, revisionist history and campus radicalism became increasingly bogged down in the miasma created by identity politics and postmodernism, with their generally reactionary agendas. At that point, the weaknesses and political confusion of the underlying approach, there from the start, became much clearer. A People’s History, as a compilation of 1960s and 1970s revisionist scholarship, expressed its contributions as well as its limitations.

It is not coincidental that the new studies developed concomitantly to the emergence of identity politics and the promotion of affirmative action on the campuses, as US liberalism, trade unionism and the Democratic Party sought a new constituency for their policies outside of the working class. The new academic history served this political development and has, in turn, been richly fed by it. Indeed, in the more facile historical studies, the oppressed groups of the past are presented as mere transpositions of the various “interest groups” that emerged in the 1970s. It should not be surprising that the new history treated political economy and politics superficially—or not at all—and tended to present the “agency” of oppressed groups as independent of the historical process, or as introduced to it by human will or moral choice.

With this in mind, it is perhaps easier to confront the apparent contradiction between Zinn the historian and Zinn the political commentator, who wrote frequently for the Nation and the Progressive and whose views were much sought-after in radical circles.

As an historian, Zinn found nothing progressive in “the system.” Of the two-party system, Zinn wrote, “to give people a choice between two different parties and allow them, in a period of rebellion, to choose the slightly more democratic one was an ingenious mode of control.” Zinn wrote that elections are times “to consolidate the system after years of protest and rebellion.” And he invariably presented reforms as means by which the elite bought off the loyalty of the masses.

Yet the same Zinn, who (incorrectly) found few differences to pause over between the Republican Party of Lincoln and the pro-slavery Democratic Party of Jefferson Davis, called for a vote for Barack Obama in 2008, arguing that Obama, while not good, was decidedly better than George W. Bush. Zinn qualified his endorsement by arguing that Democrats, once in office, could be pressured to enact reforms, evidently drawing no conclusions from the unrelenting rightward shift of the US political system from the 1970s on.

His idolization of “resistance” in the pages of A People’s History masked a pessimistic outlook. In every case, resistance for Zinn was either co-opted or crushed by establishment control. Given this, surely the best that could be hoped for was co-option through reforms. There were no strategic lessons to be drawn; this was all to repeat itself.

Zinn’s general disinterest in A People’s History in politics and thought—the conscious element in history—becomes more pronounced in his last chapters. By the time he arrives in the 1970s, even Zinn’s resisters appear less heroic: angry farmers, trade unionists, Wobblies, and Socialists have given way to proponents of identity politics, environmental reform, and the pro-Democratic Party anti-war movement.

Zinn’s concluding chapter, “The Coming Revolt of the Guards,” in which he ponders how “the system of control” might ultimately be broken, brings into the clear the link between his politics and his history.

“The Guards” referenced in the chapter title, as it turns out, are workers. “[T]he Establishment cannot survive without the obedience and loyalty of millions of people who are given small rewards to keep the system going: the soldiers and police, teachers and ministers, administrators and social workers, technicians and production workers, doctors, lawyers, nurses, transport and communications workers, garbage men and firemen,” according to Zinn. “These people—the employed, the somewhat privileged—are drawn into alliance with the elite. They become the guards of the system, buffers between the upper and lower classes. If they stop obeying, the system falls.”

“The American system is the most ingenious system of control in world history,” Zinn writes. “With a country so rich in natural resources, talent, and labor power the system can afford to distribute just enough wealth to just enough people to limit discontent to a troublesome minority.”

These words reflected the demoralized perspective of the “New Left” and the ideological influences of elements such as the Frankfurt School, Marcuse and others who wrote off the revolutionary role of the working class, viewing it as a reactionary mass that had been bought off by the capitalist system. Included in an updated version of the book in published in 2003, they now seem quite dated.

These considerable theoretical and political limitations notwithstanding, Zinn’s contributions in A People’s History of the United States—its presentation of the crimes of the US ruling class and the resistance of oppressed groups—are significant. The book deserves its audience.