An audience of 95 students, academics and workers came to hear David North, chairman of the World Socialist Web Site International Editorial Board, deliver this lecture on Robert Service’s biography of Leon Trotsky at the Bernard Sunley theatre at St. Catherine’s College, University of Oxford on Wednesday evening.

The composition of the audience was international, with attendees from South Africa, China, Sri Lanka, India, Turkey, France and several other countries. The audience listened attentively for more than one hour before asking a number of questions.

Several audience members were either students of Service or knew of his leading position on the Oxford faculty. One questioner expressed his astonishment that Service had not attended the lecture to defend his work.

Earlier reviews and lectures by North on this subject include: “In defence of Trotsky’s ‘immense and enduring historical significance’”; “Historians in the Service of the ‘Big Lie’” and “In The Service of Historical Falsification.”

***

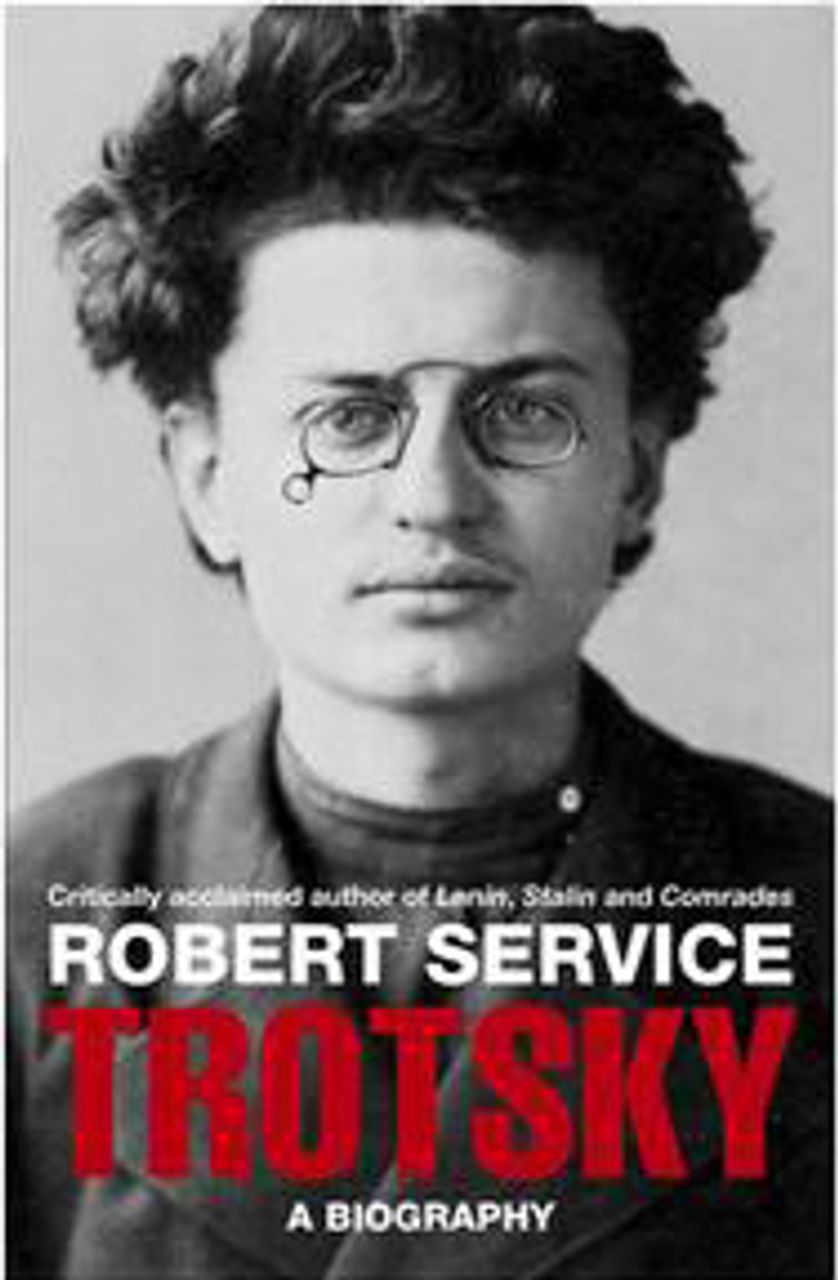

Since the publication last autumn of Robert Service’s biography of Leon Trotsky, I have written one lengthy review and delivered two lectures, the first in London and the second in Sydney. This is my third lecture on this book. What, one might reasonably wonder, is there to add to what I have already written and said? This thought crossed my mind as I began to prepare for this evening’s meeting. Would I find myself in the position of having to repeat what I have already said, albeit before a new audience? This will not, at least for the most part, be the case. Some repetition is unavoidable, but there is much that remains to be said.

Returning to Mr. Service’s biography after a hiatus of several months, two things became clear to me. First, the book is even worse than I had remembered it to be. Second, I had not identified all the factual errors, half-truths, distortions, falsifications and outright slanders that are to be found in Mr. Service’s biography. Indeed, the work of identifying all the errors in his book is a job that could keep a number of Oxford history department graduates busy for months. What I wrote in my initial review was not an exaggeration: the refutation of every statement that is factually incorrect, lacks the necessary substantiation and violates accepted standards of scholarship would require a volume almost as long as Service’s book. There are statements and assertions that are completely unacceptable, from a purely professional standpoint, in every chapter.

Previously, I called attention to some of the most malicious passages in Mr. Service’s biography—that is, his scurrilous portrayal of Trotsky’s character and personal life. As he acknowledged in his introduction, Service set out to discredit the heroic image of Trotsky that had emerged from the pages of Isaac Deutscher’s magisterial biographical trilogy [The Prophet Armed, Unarmed and Outcast], and which had exerted significant influence on a generation of radicalized youth in the 1960s. Service’s intention was to discredit Trotsky not only as a political figure, but also as a man: to present him as an ungrateful son, a faithless and philandering husband, a cold and uncaring father, a rude, disruptive and untrustworthy comrade, and, finally, as a mass murderer, a man who “revelled in terror.” (Trotsky, p. 497) In short, Trotsky is portrayed as one of the monsters of twentieth-century political history. I also questioned Mr. Service’s obsessive fixation with Trotsky’s Jewish ancestry, which he dealt with in a manner that would not fail to delight anti-Semites.

The detailed exposure of Service’s blackguarding of Trotsky’s personality left insufficient time to examine his treatment of Trotsky’s politics and ideas. I should point out, however, that Service had declared that he was not particularly interested in examining what Trotsky said, wrote, or, for that matter, did. Service wrote that he intended “to dig up the buried life.” (p. 4) Service proclaimed that he was as interested in “what Trotsky was silent about as what he chose to speak or write about.” According to Service, Trotsky’s “unuttered basic assumptions were integral to the amalgam of his life.” (p. 5)

This approach suited Mr. Service’s purposes, both commercial and political. First, it spared him the trouble of actually reading Trotsky’s major works, let alone working systematically through his vast legacy of published and unpublished papers. At any rate, Service would not have been able to engage in serious research, even if he had been inclined to. His biography of Trotsky was produced in accordance with a commercial formula that he had worked out with his publishers (Macmillan in Britain, Harvard University Press in the United States). The Trotsky biography is the third large book by Service that has been brought on to the market in the space of just five years. The first book, a biography of Stalin, was published in 2005. It consisted of 604 pages of text, neatly packaged in five parts. Each part had 11 chapters, between 10 and 13 pages in length. Service’s second book, Comrades, was published two years later, in 2007. Marketed as an authoritative history of world communism, this volume consisted of 482 pages of text, organized in six parts. Each part had six chapters. Each chapter consisted of 10 to 12 pages.

Comrades is a travesty of political and intellectual history. Service’s introduction to the volume, a wild romp through the origins of Marxism, reads like the first draft of a Monty Python skit. Service informed his readers, among other things, that “Marx claimed to have turned Hegel upside down” and that he never “condoned Ricardo’s advocacy of private enterprise.” Having so expeditiously dealt with philosophy and political economy, Service proclaimed: “Crucial to Marxism was the dream of apocalypse followed by paradise. This kind of thinking existed in Judaism, Christianity and Islam.” (p. 14) The volume sparkles with scores of such brilliantly thoughtful observations.

Service set to work on his next venture. With Trotsky, published in 2009, Service and his publishers achieved a perfect equilibrium between the commercial timetable and the content manufacturing process. Trotsky has 501 pages of text, packaged in four parts, 13 chapters each. A total of 52 chapters, each consisting of nine to 10 pages. Thus, one can reasonably assume, Service was expected to churn out a chapter a week, and complete the writing in just one year. Considering the additional months required for editing, proof-reading, typesetting and printing, the biennial publishing schedule did not leave Service all that much time for reading, sifting through and evaluating documents, and thinking. This would partly explain the astonishing number of factual mistakes in his biography.

However, even if Mr. Service had negotiated a more relaxed schedule, the result still would have been largely the same. Service set out to produce an anti-Trotsky and anti-Trotskyist hatchet job that, by its very nature, precluded a principled and thoughtful engagement with Trotsky’s writings and ideas. Ignoring Trotsky’s writings facilitated the distortion of his ideas. For Service, the truth or untruth of any particular statement, or whether one or another judgment was based on credible evidence, were not matters about which he needed to concern himself. In writing about Trotsky, no absurdity was too grotesque.

That Trotsky was one of the great revolutionary intellectuals of the twentieth century is not a statement that serious historians—including those who have no sympathy for his politics—would challenge. He was, indisputably, a writer of exceptional force. He was the rarest of political figures—one who commanded the attention of the world through the power of his writings. Separated from all the conventional trappings of power, living in isolated exile—on an island off the coast of Istanbul in Turkey, later in provincial villages in France and Norway, and finally in a suburb of Mexico City—Trotsky’s words influenced world opinion.

His enemies continued to fear him. The very mention of his name would send Hitler into a rage. Even the mighty Stalin, ensconced in the Kremlin, with a vast apparatus of terror at his command, feared Trotsky. The Soviet historian, the late General Dmitri Volkogonov, wrote, “Nearly everything about or by Trotsky was translated for him [Stalin], in one copy. … He had a special cupboard in his study in which he kept … virtually all of Trotsky’s works, heavily scored with underlinings and comments. Any interview or statement that Trotsky gave to the Western press was immediately translated and given to Stalin.” [1] In a remarkable passage, Volkogonov, who had access to Stalin’s private papers, wrote that

Trotsky’s spectre frequently returned to haunt the usurper. … [Stalin] feared the thought of him. … He thought of Trotsky when he had to sit and listen to Molotov, Kaganovich, Khrushchev and Zhdanov. Trotsky was of a different calibre intellectually, with his grasp of organization and his talents as a speaker and writer. In every way he was far superior to this bunch of bureaucrats, but he was also superior to Stalin and Stalin knew it. … When he read Trotsky’s works, such as The Stalinist School of Falsification, An Open Letter to the Members of the Bolshevik Party, or The Stalinist Thermidor, the Leader almost lost his self-control. [2]

Seventy years after his death, Trotsky’s works remain in print in many languages throughout the world. Indeed, of all the principal representatives of classical Marxism—with the possible exceptions of Marx and Engels—Trotsky remains the most widely read. The words “Revolution Betrayed,” “uneven and combined development,” “Permanent Revolution,” and “Fourth International”—linked with the name of Trotsky—evoke key motifs of the political experience of modern history. As long as the Russian Revolution remains a subject of interest, controversy and inspiration—that is, for generations to come—Trotsky’s monumental History of the Russian Revolution will retain its hold on readers’ intellect, imagination and emotions. Trotsky was, clearly, a major political thinker. As a well-known contemporary historian, Baruch Knei-Paz (who is not a Trotskyist) aptly wrote in a 1978 study of Trotsky’s thought:

A great deal has been written about Trotsky’s life and revolutionary career—both in and out of power—but relatively little about his social and political thought. This is perhaps only natural since his life contained many sensational moments and he is, even now, and perhaps not unjustly, considered to be the quintessential revolutionary in an age which has not lacked in revolutionary figures. Yet his achievement in the realm of theory and ideas is in many ways no less prodigious: he was among the first to analyse the emergence, in the twentieth century, of social change in backward societies, and among the first, as well, to attempt to explain the political consequences which would almost invariably grow out of such change. He wrote voluminously throughout his life, and the political thinker in him was no less an intrinsic part of his personality than the better-known man of action. [3]

Now, let us listen to Service: “Always he [Trotsky] wrote whatever was in his head.” (p. 78) Trotsky “made no claim to intellectual originality: he would have been ridiculed if he had tried.” (p. 109) “He refused to bother himself with research on most questions currently bothering the party’s intellectual elite…” (p. 109) “Intellectually he flitted from topic to topic…” (p. 110) “He simply loved to be seated at a desk, fountain pen in hand, scribbling out the latest opus…” (p. 319) “His thought was a confused and confusing ragbag…” (p. 353) “He spent a lot of time in disputing, less of it in thinking. … This involved an ultimate lack of seriousness as an intellectual.” (p. 356) “His articles were full of schematic projections, shaky reasoning and ill-considered slogans.” (p. 397)

As one reads such passages, one is simply amazed by their sheer stupidity and crudity. Does their author expect such nonsense to be taken seriously? Does he himself believe it? Service provides no examples of Trotsky’s “confused and confusing ragbag of ideas.” Service does not attempt to analyze, or even present an adequate summary of, a single work by Trotsky. Characterizations such as those cited above are dished up without any examination of, or citation from, the actual texts. Even the most significant concepts and ideas associated with Trotsky—such as the theory of permanent revolution and his analysis of the socio-economic foundations of the Soviet Union as a degenerated workers’ state—are not explained. To the extent that even brief references are made to specific works of Trotsky, it is done in a manner calculated to make their author and his ideas appear ridiculous.

Service is not the first to employ this technique against Trotsky. In fact, his method bears a striking resemblance to that used in the international anti-Trotsky campaign mounted by the Soviet bureaucracy and allied Stalinist parties, such as the Communist Party of Great Britain, in the late 1960s and early 1970s. As a young graduate student during that period, studying Soviet history, Mr. Service would have been aware of this campaign. The writings of the Stalinist Betty Reid, the CPGB’s anti-Trotsky specialist, were widely circulated on university campuses in Britain. During those years, the Soviet bureaucracy became increasingly concerned about the spread of Trotskyist influence among radicalized youth. But as Stalin’s crimes had already been discredited by the revelations of Khrushchev, it was no longer possible for the Kremlin’s ideological operatives to simply denounce Trotsky as a “fascist wrecker,” as had been the style in the 1930s and 1940s. Other forms of insidious falsification had to be developed. The gross misrepresentation of Trotsky’s writings—specifically, making them appear absurd or as the ravings of a lunatic—played a central role in the renewed assault on Trotskyism. Of course, the attempt to discredit Trotsky’s ideas required that citations from his writings be kept to a minimum. In an important article entitled “The Revival of Soviet Anti-Trotskyism,” written in 1977, the late Robert H. McNeal, a noted American scholar, described the Stalinist method:

There is quite a lot that cannot be stated in the revived version of Soviet anti-Trotskyism. His writings cannot be cited in full bibliographical form, nor very frequently. One finds relatively frequent reference to the titles (never additional publication information) Permanent Revolution and My Life, but very little else. This is a sensible precaution. No need to service the enemy by providing subversive reading lists, particularly considering the readers in countries whose libraries contain Trotskyist works. This vagueness on primary sources facilitates their interpretation. … It is vaguely asserted that Trotsky slandered the Soviet Union, denied that it was socialist, an assertion that is regarded as too absurd to require rebuttal, but the content of Trotsky’s critique of Stalinism is never described. [4]

Service writes that Trotsky’s “written legacy should not be allowed to become the entire story” and that “It is sometimes in the supposedly trivial residues rather than in the grand public statements that the perspective of his career is most effectively reconstructed.” (p. 5) He goes on to claim that Trotsky’s published autobiography is a dishonest attempt to conceal the truth of his life, and that “The excisions and amendments tell us about what he did not want others to know.” (p. 5) These statements exemplify a method of falsification that is a variant of the Stalinist method identified quite precisely by McNeal.

The method employed by Service is connected to the political outlook that suffuses his writing. Service’s detestation of Trotsky is the mirror reflection of his admiration of Stalin. Having reviewed Service’s mocking and derisory characterizations of Trotsky, let us examine the professor’s evaluation of Stalin. In the 2005 biography Service describes Stalin as “an excellent editor of Russian-language manuscripts.” Service does not cite a single manuscript in which this excellence is demonstrated. Nor does he mention that Stalin, as dictator, did most of his editing with an executioner’s bullet. (Stalin, p. 115) Rather, the tributes continue: “In fact,” writes Service, “Stalin was a fluent and thoughtful writer even though he was no stylist.” (p. 221) Not an opinion. A fact! This is in contrast to Trotsky, who as Service told us, “wrote whatever was in his head.” Yes, Stalin was by no means perfect. “He was a mass killer with psychological obsessions,” Service notes dolefully. But “he thought and wrote as a Marxist.” (p. 379) His Foundations of Leninism was “a work of able compression.” (p. 221) “Stalin,” writes Service, “was a thoughtful man and throughout his life tried to make sense of the universe as he found it. He had studied a lot and forgotten little. … He was not an original thinker nor even an outstanding writer. Yet he was an intellectual to the end of his days.” Summing Stalin up, at the biography’s conclusion, Service declares, “But exceptional he surely was. He was a real leader. He was also motivated by the lust for power as well as by ideas. He was in his own way an intellectual, and his level of literary and editorial craft was impressive. About his psychological traits there will always be controversy.” (p. 603)

Service’s aim in his Trotsky biography was to discredit the favorable image that emerged from the earlier biographies written by Isaac Deutscher and the French historian, Pierre Broué. The purpose of Service’s biography of Stalin was the exact opposite. While, for Service, the writing of the Trotsky biography was a labor of hate, his work on Stalin was a labor of love. The existing image of Stalin was “overdue for challenge,” he wrote. “This book is aimed at showing that Stalin was a far more dynamic and diverse figure than has conventionally been supposed.” (Stalin, p. x) Service conceded that Stalin “was a bureaucrat and a killer.” But “he was also a leader and editor, a theorist (of sorts), a bit of a poet (when young), a follower of the arts, a family man and even a charmer.” (p. x) Much of the same, by the way, could be said of Goebbels and Goering, not to mention Hitler.

Perhaps Service imagined that he was providing his readers a nuanced portrait, a blending of contradictory characteristics. But what he really presented was a variation of the worst of movie clichés—the mass murderer who tucks his children into bed and gently kisses them goodnight. But what did he leave us with? Actually, with a political portrait quite similar to that drawn by Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, in his notorious speech on history in November 1987:

There is now much discussion about the role of Stalin in our history. His was an extremely contradictory personality. To remain faithful to historical truth we have to see both Stalin's incontestable contribution to the struggle for socialism, to the defense of its gains; the gross political errors, and the abuses committed by him and by those around him, for which our people paid a heavy price and which had grave consequences for the life of our society. [5]

Both Service and Gorbachev are prepared to accept that Stalin committed crimes. But the emphasis is on his positive achievements. In the first paragraph of the Stalin biography, Service declared: “Although Lenin had founded the USSR, it was Stalin who decisively strengthened and stabilized the structure. Without Stalin, the Soviet Union might have collapsed decades before it was dismantled in 1991.” (Stalin, p. 3) These words could have been written by a member of the Soviet Politburo! A more emphatic apology and justification for Stalin’s policies is hard to imagine. Stalin decisively strengthened and stabilized the structure of the USSR. It would have collapsed without him, decades before its dissolution in 1991.

With these words, all of Stalin’s actions and crimes are rationalized and justified: the crushing of the Left Opposition in the 1920s, the horrors of collectivization, the Moscow Trials and the Terror of the late 1930s, the disorientation and betrayals that facilitated the victories of fascism in Europe, the decapitation of the Red Army leadership in 1937-38 and the Stalin-Hitler Pact, which led to the unnecessary loss of millions of Soviet lives after the German invasion in June 1941, the mismanagement of the Soviet economy and the stultification of its intellectual life, the murder of its finest writers, philosophers, scientists, the revival of anti-Semitism, and the besmirching of Marxism and socialist ideals, within the Soviet Union and internationally. All this is legitimized by Service as necessary for the stabilization and preservation of the USSR! Service overlooks the fact that the structure left behind by Stalin staggered from crisis to crisis, and that the generation of bureaucrats that rose to power under his tutelage presided over the stagnation and breakdown of the Soviet Union.

Service goes so far to imply that the terror was a legitimate response by Stalin to threats confronting the USSR:

Chief among his considerations was security, and he made no distinction between his personal security and the security of his policies, the leadership and the state. Molotov and Kaganovich in their dotage were to claim that Stalin had justifiable fears about the possibility of a “fifth column” coming to the support of the invading forces in the event of war. Stalin gave some hints of this. He was shocked by the ease with which it had been possible for General Franco to pick up followers in the Spanish Civil War which broke out in July 1936. He intended to prevent this from ever happening in the USSR. Such thinking goes some way to explaining why he, a believer in the efficacy of state terror, turned to intensive violence in 1937-38. (Stalin, p. 347-48)

Service accepts as credible the lying justifications for the terror given by Stalin’s co-butchers, Molotov and Kaganovich, who affixed their names to thousands of execution orders in the 1930s. There exists no evidence whatever that Stalin’s decision to exterminate the Bolshevik Old Guard and vast sections of the revolutionary socialist intelligentsia had anything to do with “justifiable fears” that a right-wing coup against the Soviet state was being prepared. By implying that events in Spain—where well-known army officers, long identified with the extreme right, launched a coup against the Republican government in Spain—spurred Stalin to launch the terror, Service bestows legitimacy on the monstrous allegations hurled by State prosecutor Vyshinski against the Old Bolshevik defendants at the Moscow Trials. It must be pointed out that plans for the physical destruction of the Old Bolsheviks were far advanced by the time the Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936. The murder of Kirov had taken place in December 1934. Zinoviev and Kamenev and countless others had been in prison since 1935. Preparations for the first Moscow trial—which included placing Zinoviev, Kamenev and other imprisoned potential defendants under extreme pressure, which included torture, to provide confessions—had been underway for months. If there was any foreign event that “inspired” Stalin to wipe out his old comrades, it was not the right-wing coup in Spain. Rather, it was the “Night of the Long-Knives” in Germany in June 1934—that is, Hitler’s assassination of his old party associates in the leadership of the SA storm troopers.

It is true that Stalin launched the terror to deal with threats to his regime. But those threats came not from the fascist right, but from the socialist left. Stalin’s fear that social discontent within the Soviet Union would lead to a resurgence of Bolshevik tendencies, above all that led by Trotsky, has been well-documented—especially by the brilliant Russian Marxist historian, Vadim Z. Rogovin. Not surprisingly, Rogovin’s seven-volume history of the struggle of the socialist left and Trotskyist opposition to Stalinism is not included by Service in the bibliographies of his Stalin and Trotsky biographies.

Service’s defense of Stalin is continued in his biography of Trotsky. He notes with disapproval that “Trotsky had provided arguments that discredited the reputation of Stalin and his henchmen, and it was all too easy for writers unthinkingly to adopt them as their own.” (Trotsky, p. 3) Service continues:

Trotsky was wrong in many cardinal aspects of his case. Stalin was no mediocrity but rather had an impressive range of skills as well as a talent for decisive leadership. Trotsky’s strategy for communist advance anyway had little to offer for the avoidance of an oppressive regime (p. 3)

As for the unpleasant aspects of Stalin’s regime, the source of these problems lay with Trotsky, whose “ideas and practices laid several foundation stones for the erection of the Stalinist political, economic, social and even cultural edifice.” (p. 3) Later in the biography, blatantly falsifying Trotsky’s famous work of literary criticism, Literature and Revolution, attributing to the author views that are the exact opposite of what is written in the book, Service states: “When all is said and done … it was Trotsky who laid down the philosophical foundations for cultural Stalinism.” (p. 318)

Service’s defense of Stalin against Trotsky’s writings is extraordinarily vituperative: “As for the charge that Stalin was an arch-bureaucrat, this was rich coming from an accuser who had delighted in unchecked [?] administrative authority in years of his pomp.” (p. 3) The tirade continues:

Even Trotsky’s claim that Stalin was uninterested in aiding foreign communist seizures of power fails to withstand scrutiny. Moreover, if communism had been victorious in Germany, France or Spain in the interwar years, its banner-holders would have been unlikely to have retained their power. And if ever Trotsky had been the paramount leader instead of Stalin, the risks of a bloodbath in Europe would have been drastically increased. (p. 3)

Whose scrutiny? Service himself does not examine in detail any of the major revolutionary conflicts—in Britain, China, Germany, France and Spain, to name a few—that were the subject of Trotsky’s polemics during the 1920s and 1930s. But the statement itself is not one that could be made by any reputable and honest historian. The destructive role of Stalinism during the “low dishonest decade” [6] that preceded the outbreak of World War II, the devastating impact of its duplicitous, cynical and murderous activities on the European and international workers’ movement, was burnt into the consciousness of an entire generation who lived through the terrible events of the 1930s. George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia is only the most famous account of the Stalinist nightmare.

There are countless books in which the Stalinist subversion of the Spanish revolution, including the repression of the left and the murder of POUM leader Andrés Nin, has been recorded for history. The transformation of the Communist International into a corrupt instrument of Soviet foreign policy, led by functionaries selected and controlled by the Kremlin, is a massively documented historical fact. The Seventh Congress of the Comintern, held in 1935, committed the national Communist parties to the class collaborationist perspective of “Popular Front” alliances with “liberal” and “democratic” bourgeois parties. Service fails to mention this Congress, which Trotsky predicted would set the stage for the formal dissolution of the Comintern. As later noted by the historian E.H. Carr, who wrote a famous book in which he subjected Stalin’s foreign policy to “scrutiny”:

…It was significant that no further congress, and no major session of IKKI [Executive Committee of the Communist International], was ever again summoned. Comintern continued to discharge subordinate functions, while the spotlight of publicity was directed elsewhere. Trotsky’s verdict that the seventh congress would ‘pass into history as the liquidation congress’ of Comintern was not altogether unfair. The seventh congress pointed the way to the dénouement of 1943. [7]

Alongside his outright falsifications, Service issues ex cathedra pronouncements whose nonsensical character must become apparent to any reader who actually thinks about what he is reading. How does Service know that “if communism had been victorious in Germany, France or Spain in the interwar years, its banner-holders would have been unlikely to have retained their power”? What is the basis of this judgment? If the working class would actually have come to power in two of the most economically and culturally advanced countries in Western Europe, and, in addition, held power in the strategic Iberian peninsula, how would these revolutionary regimes have been overthrown? Through the efforts of a capitalist Britain, perhaps led by Winston Churchill? Does Service assume that the British working class—whose opposition to the anti-Bolshevik efforts of the imperialist Lloyd George government in 1918-1920 contributed significantly to the survival of Soviet Russia—would have supported a military campaign to restore capitalism in France, Germany and Spain?

Service never poses another essential question: What would have been the impact of such revolutionary advances by the working class in the major European centers of capitalism on the development of the Soviet Union? Trotsky always stressed that the defeat suffered by the revolutionary movement in Western Europe was the decisive factor in the development of the Stalinist dictatorship. The repudiation of the revolutionary internationalism of the early Bolshevik regime and its replacement by the Stalin-Bukharin theory of socialism in one country was a political adaptation to setbacks in Western Europe, particularly in Germany. Conversely, Trotsky held that a renewal of revolutionary struggles in the capitalist centers would transform the political situation in the Soviet Union. As he wrote in 1936:

The first victory of a revolution in Europe would pass like an electric shock through the Soviet masses, straighten them up, raise their spirit of independence, awaken the traditions of 1905 and 1917, and acquire for the Fourth International no less significance than the October Revolution for the Third. [8]

Service never directly explains Trotsky’s conception of the relationship between the fate of the Soviet Union and the development of international revolution. But his biography is not the work of a politically neutral scholar. That would not necessarily condemn the work. What does condemn the biography is that the political views and objectives that motivate the work require historical falsification. Service’s political hatred of Trotsky’s perspective of world revolution, and his support for Stalin’s nationalist program, is apparent to those who recognize the pro-Stalin subtext that pervades the Trotsky biography. Service writes:

Trotsky prided himself on his ability to see Soviet and international affairs with realism. He deceived himself. He had sealed himself inside preconceptions that stopped him from understanding the dynamics of contemporary geopolitics. (p. 3)

For Service, the “preconceptions” are those of revolution and Marxian internationalism. The “dynamics of contemporary geopolitics,” as Service (much like Stalin) conceives them, proceed from the primacy of the national state and its interests and the indestructibility of capitalism.

Let us return to the most bizarre assertion of all, that is, to Service’s claim that “if ever Trotsky had been the paramount leader instead of Stalin, the risks of a bloodbath in Europe would have been drastically increased.” One is compelled to ask: What could Trotsky possibly have done that would have made the loss of human life in the Europe of the 1930s and 1940s worse than it actually was? Apart from the atrocities committed by Stalin within the USSR, his policies—beginning with the defeat of the German working class in 1933—set into motion a chain of events that culminated in the very real bloodbath of World War II. The war cost the lives of approximately 50 million people in Europe—including 27 million Russians, six million Germans, six million Jews and three million Poles. Service seems to be arguing, however circuitously, that millions more would have died if Trotsky’s perspective of socialist revolution had prevailed. The actual loss of life that occurred as a consequence of the failure of revolution—the victory of fascism in Germany and the outbreak of World War II—was less than it would have been had the socialist revolution succeeded. The conclusion that Service invites his readers to draw is that given the choice between victory of socialist revolution and the victory of fascism, the latter is the lesser evil.

The claim that underlies this position is that Trotsky was a violent man, indifferent to human life and suffering, willing to sacrifice countless lives for the sake of revolution. As Service states at the conclusion of his biography, Trotsky “fought for a cause that was more destructive than he had ever imagined.” (p. 501)

Portraying Trotsky as a cold-blooded fanatic, brutally indifferent to human life, Service provides an example of his subject’s ruthlessness. Trotsky, he writes, “displayed his complete moral insouciance when telling his American admirer Max Eastman in the early 1920s that he and the Bolsheviks were willing ‘to burn several thousand Russians to a cinder in order to create a true revolutionary American movement.’ Russia’s workers and peasants would have been interested to know of the mass sacrifice he was contemplating.” (p. 313) This passage is calculated to send a shudder down the spines of its readers. What type of monster of political fanaticism, they must wonder, could contemplate such an act?

But did Trotsky actually say this? And, if he did, in what context? Why did Max Eastman, despite learning of the terrible plan, become one of Trotsky’s most devoted international supporters during the 1920s? And, still later, the principal translator of Trotsky’s writings into English? The passage that I have just quoted appears on page 313 of Service’s Trotsky, in Chapter 33, entitled “On the Cultural Front.” Service cites as his source the memoirs of Max Eastman, Love and Revolution: My Journey Through an Epoch. And, indeed, on page 333 of that book, we find Eastman’s account of his discussion with Trotsky.

Eastman’s story is wonderfully told. It is of his first meeting with Trotsky, which took place in Moscow in 1922, during the Fourth Congress of the Communist International. Eastman was, he relates, anxious to speak to Trotsky about a problem that had been troubling him. The American socialist movement was dominated by Russian immigrants. They were monopolizing the leadership of the young Communist party. An opportunity arose for Eastman to approach Trotsky during a session of the congress. Eastman was surprised to find that Trotsky’s appearance was very different from the well-known Mephistophelian caricatures of the newspapers. Trotsky, Eastman recalled, looked “more like a carefully washed good boy in a Sunday School class than like Mephistopheles.” [9] Eastman requested an appointment, which Trotsky immediately granted. They met again the next day at Trotsky’s office at the Military Revolutionary Soviet.

Trotsky, as Eastman humorously described him, was “certainly the neatest man who ever led an insurrection.” But what particularly surprised Eastman was Trotsky’s “quietude.” Newspaper descriptions of Trotsky that portrayed him as nervous and excitable “seemed,” wrote Eastman “almost a libel against this gracious person who listened with such courtesy to the bad French in which I wrestled forth my ideas.” Eastman explained to Trotsky that the dominant role played by Russian socialists “made it impossible to get an American revolutionary movement started.” To make matters worse, though most of them were Mensheviks before October 1917, “they think they created the October Revolution.” Adopting a jocular tone, Eastman compared the posturing ex-Mensheviks to a young rooster who crows “in a loud falsetto voice because some hen who is old enough to be his grandmother has laid an egg.” Trotsky, Eastman remembered, was amused by this comment. He then made the remark in French which Eastman recalled verbatim: “Mais nous sommes préts à brûler quelques milliers de Russes afin de créer un vrai movement révolutionnaire Américain.” Eastman places within parentheses the English translation: “But we are ready to burn up a few thousand Russians to create a real American revolutionary movement.” [10]

Service, it is clear, has deliberately and maliciously misrepresented the remark made by Trotsky. He was jesting with Eastman, who understood that Trotsky was not talking about incinerating Russian workers and peasants, but of reducing the influence of pompous ex-Menshevik Russian immigrants in the American socialist movement. Moreover, Service, with the intention of enhancing the impact of his lie, adds words that are not found in Eastman’s text. The words “to a cinder” do not appear in the original. So Service has transformed a humorous anecdote, recalled by Eastman many decades later—and one which presents Trotsky in a favorable light, as a patient, humorous and cultured man—into an example of a revolutionary fanatic’s horrifying inhumanity.

Is this a trivial, let alone innocent, mistake? Hardly. This sort of falsification has consequences. The falsification, once it has escaped detection, becomes part of the accepted historical narrative, repeated over and over in essays and books. As time passes, it becomes ever more difficult to expose the lie, let alone identify the liar who put it into circulation.

Service’s biography is a shameful and shameless compendium of distortions and falsifications. It is not sufficient for Service to misrepresent the ideas for which Trotsky lived and died. He seeks to belittle the man, to make him appear deserving of the reader’s contempt. He repeats the same insults. On page 336 Service describes Trotsky as “intensely self-righteous.” On page 381, he writes of Trotsky’s “matchless self-righteousness.” Even Trotsky’s writings are subjected to ridicule. “The mixture of tub-thumping and slipperiness,” Service writes, “was preserved in The History of the Russian Revolution.” (p. 466). He expresses amazement that people have “automatically believed” Trotsky’s account of his struggle against Stalin. “In fact the gap between the Politburo and the Opposition was never as wide as he pretended.” (p. 356) Service does not offer this statement, wholly unsubstantiated, as his own interpretation. He declares it to be a fact, and, therefore, beyond dispute! Thus, Service finds it “surprising” that a great many people “who had no sympathy for communism” nevertheless “accepted the idea that the USSR would not have been a totalitarian despotism under Trotsky’s rule.” (p. 356)

In what are among the most degraded passages in his book, Service refers contemptuously to liberal and socialist intellectuals who rallied to Trotsky’s defense during the Moscow Trials, supporting his call for a Commission of Inquiry. Their position, Service states, “reflects their naivety. They were blind to Trotsky’s contempt for their values. They overlooked the damage he aimed to do to their kind of society if he ever got the chance. Like spectators at a zoo, they felt sorry for a wounded beast.” (p. 466)

I have already shown that Mr. Service practices his profession incompetently and dishonestly. These lines expose Service as a man bereft of any respect for democratic principles. Trotsky’s right to answer his accusers and defend himself was not contingent upon his endorsement of the political institutions of the United States. Mr. Service would be well-advised to read the words with which John Dewey, the great American liberal philosopher, explained the raison d’être of the Commission of Inquiry over which he presided as chairman. Leon Trotsky, he explained, had been declared guilty of terrible crimes by the highest tribunal of the Soviet Union. Trotsky had demanded that the Soviet government seek his extradition, which would have enabled him to answer the charges against him in either a Norwegian or Mexican court. This demand had been ignored by the Soviet Union. What followed from this situation? Dewey stated:

The simple fact that we are here is evidence that the conscience of the world is not as yet satisfied on this historic issue. This world conscience demands that Mr. Trotsky be not finally condemned before he has had full opportunity to present whatever evidence is in his possession in reply to the verdict pronounced upon him in hearings at which he was neither present nor represented. The right to a hearing before condemnation is such an elementary right in every civilized country that it would be absurd for us to reassert it were it not for the efforts which have been made to prevent Mr. Trotsky from being heard, and the efforts that now are being made to discredit the work of this Commission of Inquiry. [11]

In another public statement, Dewey answered, with evident anger, the claims that Trotsky did not deserve, on account of his political views, to be defended.

In the case of Tom Mooney in San Francisco and Sacco-Vanzetti in Boston, we got used to hearing reactionaries say that these men were dangerous nuisances anyway, so that it was better to put them out of the way whether or not they were guilty of the things for which they were tried. I never thought I would live to see the day when professed liberals would resort to a similar argument. [12]

Service’s animus for the proceedings of the Commission is evident. He writes nothing of the international Stalinist campaign to sabotage and discredit the Commission, which included threats of violence against public supporters of the inquiry. Dewey’s family feared for the life of the 78-year-old philosopher. Service writes, as if something was amiss, that Dewey was Trotsky’s “favored choice as chairman” (p. 466), and that “they agreed to avoid examining the broadest questions of Trotsky’s political and moral record.” (p. 467) He applauds the resignation of the journalist Ferdinand Lundberg from the Commission before its first session. “Lundberg had come to think, justifiably, that Trotsky was a prime architect of the suppression of civil rights in the USSR which he now, as a victim, complained about.” (p. 467)

Service does not cite even one line from the transcript of the Commission’s hearing in Mexico in April 1937. He ignores Trotsky’s famous speech with which the hearing concluded, which made an overwhelming impression on the commissioners. Service states that the Commission “went on for a whole week until Dewey felt he could summarize an agreed verdict. Nobody had been in serious doubt about what it would be. Trotsky was exculpated.” (p. 467) This is a trivialization and slur on the Commission’s work. No “agreed verdict” was arrived at and delivered in Mexico. In fact, Dewey and other Commission members had travelled to Mexico as members of the “Preliminary Commission” to conduct a preliminary investigation, which included the questioning of Trotsky and the collection of relevant documents in his possession. After leaving Mexico, it prepared a preliminary report, which found that Trotsky “has established a case amply warranting further investigation.” [13] The Preliminary Commission recommended that the Commission of Inquiry continue its work. It was not until December 1937, eight months after it had questioned Trotsky in Mexico, that the Dewey Commission issued its verdict, found Trotsky to be not guilty and the Moscow Trials to be a frame up.

Upon submitting the report of the Preliminary Commission, Dewey stated:

The work of investigation is only begun. Various lines of inquiry have been opened which must be pursued until all the available facts are disclosed. Final judgment must be reserved until the different lines of investigation have been carried through to the end. [14]

Explaining the principles that motivated the work of the Commission, Dewey stated that “friendship for truth comes before friendship for individuals and factions.” He insisted that the Commission of Inquiry was “committed to one end and one end only: discovery of the truth as far as that is humanly possible. Lines are being drawn between devotion to justice and adherence to a faction, between fair play and a love of darkness that is reactionary in effect no matter which banner it flaunts.”

Dewey summed up all that was at stake in the struggle to defend historical truth against lies. If there is a question in your mind as to why our party has devoted so much time and effort to the exposure and refutation of attempts to falsify Trotsky’s life and the history of the epoch in which he lived, I urge you to read and ponder Dewey’s words, so relevant to our times, and, hopefully, adopt them as your own credo.

This year marks the seventieth anniversary of Trotsky’s assassination, on August 20, 1940, at the hands of a Stalinist agent, Ramon Mercader, in Coyoacan, Mexico. That Trotsky still remains a subject of intense controversy is not unusual. That is the fate of all truly important historical figures. But what is extraordinary is the degree to which he remains, so many years after his assassination, the subject of such unrelenting misrepresentation, falsification and outright slander. History will record that the Soviet bureaucracy never formally rehabilitated Leon Trotsky (contrary to the claim of Service, who gets even this fact wrong). Even as he was pursuing pro-capitalist policies that were to result, within little more than four years, to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev publicly declared:

Trotskyism was a political current whose ideologists took cover behind leftist pseudo-revolutionary rhetoric, and who in effect assumed a defeatist posture. This was essentially an attack on Leninism all down the line. The matter practically concerned the future of socialism in our country, the fate of the revolution. In the circumstances, it was essential to disprove Trotskyism before the whole people, and denude its antisocialist essence.

Service is merely at the back of a long line of anti-Trotsky slanderers who have been at work, in the service of political reaction, for more than 85 years. The conservative reaction against the revolutionary internationalist program of the October Revolution began in 1923 under the banner of the fight against Trotskyism. By the mid-1930s, this fight had assumed the form of the systematic physical extermination of all the surviving representatives of the Marxist political and intellectual tradition within the Soviet Union. And beyond the borders of the USSR, the Trotskyists were persecuted within the imperialist countries—both fascist and democratic. Hitler, as I have already mentioned, would start foaming at the mouth when Trotsky’s name was mentioned. In the United States, the Roosevelt administration organized the indictment and imprisonment of leaders of the Trotskyist movement. And if there was anyone in the world who hated Trotsky even more than Stalin did, it was none other than Winston Churchill. In 1937, Churchill published a book entitled Great Contemporaries. One chapter was devoted to Hitler, of whom Churchill wrote with unabashed admiration. He still had high hopes for the German Fuehrer. But another chapter was devoted to Trotsky. The language was out of control. “Like the cancer bacillus,” Churchill wrote, “he grew, he fed, he tortured, he slew in fulfillment of his nature.” [15] It should be noted that Churchill’s most vile slanders, directed against Trotsky as a man, are picked up and expanded upon by Service.

The rage of Hitler, the vituperation of Churchill, and the sadistic vindictiveness of Stalin are not difficult to explain. They were Trotsky’s contemporaries, his lesser contemporaries. They were engaged in what they knew to be life and death struggles against the revolutionary cause that he, more than any other person of his time, represented and embodied. Read the newspapers of the day. How often one finds on the front page, beneath the banner headlines reporting one or another spectacular event of the 1930s, a smaller headline that reads: “Trotsky says…” or “Trotsky predicts…” The press in this way informed its readers of Trotsky’s response to the great events of the day. But why the interest in the reaction of one man? Because that one man was the authoritative voice of world socialist revolution. Trotsky was the revolution in exile. On August 31, 1939—on the very eve of the outbreak of World War II—the French newspaper Paris-Soir reported a discussion between Hitler and the French ambassador Coulondre. Hitler expresses his regrets that war is inevitable. Coulondre asks Hitler if it had occurred to him that the only victor in the event of war will be Trotsky. “Have you thought this over,” he asked. And Hitler replied, “I know.” Reading this account, Trotsky wrote: “These gentlemen like to give a personal name to the spectre of revolution.” [16]

Service’s portrayal of Trotsky is drawn entirely from the slanders of those who stood in the camp of reaction, Stalinist and imperialist. He cannot permit the introduction of any testimony that contradicts the caricature that he presents to his readers. Moreover, Service relies on the fact that, so many years after his death, there is no one left who actually knew, respected and loved the “Old Man,” as he was known to so many of his followers. I was fortunate to have met and spoken with witnesses to Trotsky’s life: Arne Swabeck and Al Glotzer—both of whom spent weeks with Trotsky in Prinkipo in the early 1930s; the Belgian revolutionary Georges Vereeken; the German revolutionist, Oskar Hippe, and the captain of Trotsky’s guard in Coyoacan, Harold Robins. Not all of these men remained Trotskyists. But of Trotsky’s greatness and humanity they were never in doubt. Even after the passage of decades, they viewed the time they had spent with Trotsky as the most important period of their lives.

I have also met survivors of Stalin’s terror, who experienced firsthand the bestiality of the bureaucracy’s counter-revolutionary nationalist pogrom against the genuine representatives of Bolshevism, such as Revekka Mikhailovna Boguslavskaya, Tatiana Ivarovna Smilga and Zorya Leonidovna Serebriakova, whose fathers, members of the Left Opposition, were shot in 1937 or 1938. They met Trotsky when they were still children, and he seemed like a giant in their eyes. They recalled how their fathers—Mikhail Boguslavsky, Ivar Smilga and Leonid Serebriakov—would speak of “Lev Davidovich” with respect and genuine love. Though Tatiana Smilga and Zorya Serebriakova are still alive, they were not interviewed by Service. Nadezhda Joffe was the daughter of Adolph Joffe, Trotsky’s close friend, who committed suicide in November 1927 to protest Trotsky’s expulsion from the Communist Party. She had first met Trotsky as a child, in Vienna, before the 1917 Revolution. She played together with Trotsky’s young son, Lev Sedov. In contrast to Service’s portrayal of Trotsky as an uncaring father, Nadezhda remembered a man who loved children and was infinitely patient as he mediated their squabbles. Though Service cites Joffe’s memoirs, he makes no reference to her personal recollections of Trotsky.

There exist a number of important memoirs of Trotsky, in which his extraordinary personality is memorably portrayed. The American writer, James T. Farrell, travelled with John Dewey to Mexico in April 1937. Years later, in the 1950s, he wrote an account of that trip. Farrell had observed Trotsky closely, during the week in which he spent hours answering questions put to him by the members of the preliminary commission. Trotsky was under crushing political and personal pressure. He was all too aware of the horror that was unfolding in Moscow, where his old comrades had already been murdered or were awaiting execution. His youngest son, Sergei, had already disappeared. Trotsky was compelled to answer questions in a language that was not his own. Trotsky, Farrell recalled

gave the impression of great simplicity, and of extraordinary control over himself. He was a decisive and noncasual person. He spoke with remarkable precision. His manners were as impeccable as his clothes, and he was a man of charm. His gestures were very graceful. He was extraordinarily alert. At times it seemed as though his entire organism were subordinated to his will. His voice was anything but harsh. …

He was taut, like a bow drawn tightly. It would never snap, but it would vibrate at the slightest ripple of one’s breath. His temperament was vibrant. He was a man of tremendous intellectual pride and of self-confidence. He was intolerant of stupidity, of what he deemed to be stupid, and his simplicity and extraordinary graciousness seemed like an acquisition of experience. He was a man of genius, of will, and of ideas. He might even be called an archetype of the civilized, highly cultivated Western European. He was a man of the West, and in this unlike the majority of current men in power in the Soviet Union. His Marxian faith was a faith in ideas. We can properly say that Trotsky was a great man. [17]

Farrell offered this account of Trotsky’s testimony:

In Mexico, Dewey remarked that Trotsky had spoken for eight days and had said nothing foolish. And what Trotsky said exposed a world of horror, of tragedy, of degradations of the human spirit. “When people get accustomed to horrors,” wrote the Russian poet Boris Pasternak, “these form the foundations of good style.” The horrors of history were a basic ingredient of Trotsky’s style. His masterful irony is, like all great irony, a protest because the horrors of history loom so overwhelmingly in the face of the reason of man. And he was a man of history in the sense that most of us are not and cannot be. … And as he talked, his style, his thought, his irony gave the hearings a tone which reduced the impact of the horrors of history which were revealed—the tale of war, of revolution, of idealism turned to cynicism, of the breaking of brave men, the betrayals of honor, truth, and friendship, the perversions of truth, the sufferings of families and of the innocent, the revelation of how the Revolution and the society which had become the hope of so many in the West was really a barbarism practically unparalleled in modern history. Read the cold print of his testimony and all this is clear. Some of Trotsky’s interpretive and causal explanations may vary from our own, but the facts, the revelations, the horrors are all there. And as Trotsky talked, accepting full moral responsibility for all his own acts when he was in power, his style gave this testimony an almost artistic character. [18]

I have quoted this passage at such length because you must hear it. You have an intellectual and moral right to hear it. The younger generation has been largely cut off intellectually from the revolutionary experiences of the twentieth century. For so many years, we have lived in an environment of political and intellectual reaction. The events of the past century are falsified, or, almost as bad, simply not written and talked about. There is a danger that the young generations, coming to maturity in the first decades of the twenty-first century, will not know what they must know of the great events of the twentieth century, of its revolutions and the counter-revolutions. Of the wars, and the efforts to put an end to them. And they will not hear the sound of the great voices of the past, and the words they spoke.

We are entering into a new epoch of revolutionary struggle. Of this there are growing and increasingly apparent signs. The gulf between the few who are rich, rich beyond anything that is rational and comprehensible, and the great mass of the world’s human beings grows ever greater. The economic system, designed to perpetuate and add to the wealth of the rich, assumes before our eyes an ever-more irrational character. The global problems metastasize, producing social and ecological catastrophes. The operations of privately owned corporations ever more obviously endanger the very survival of the planet. The growing awareness of these dangers, the anger over inequality and injustice, is mounting. A change in mass consciousness is now underway. But the development of consciousness must be nourished with the lessons of history. The great voices of the past, including that of Leon Trotsky, must be revived, so that we can learn from and be inspired by them.

Notes:

[1] Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1988), p. 228.

[2] Ibid., pp. 254-56.

[3] The Social and Political Thought of Leon Trotsky (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978), p. viii.

[4] Studies in Contemporary Communism, Vol. X, Nos. 1 & 2, Spring/Summer 1977, p. 10.

[5] The New York Times, November 3, 1987.

[6] “September 1, 1939,” by W.H. Auden [http://www.poemdujour.com/Sept1.1939.html]

[7] Twilight of the Comintern, 1930-35 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1982), p. 427.

[8] The Revolution Betrayed (London: New Park, 1967), p. 290.

[9] Love and Revolution, p. 332.

[10] Ibid., p. 332-3.

[11] John Dewey: The Later Works, 1925-1953, Volume 11: 1935-1937, Essays and Liberalism and Social Action, Edited by Jo Ann Boydston (Carbondale and Edwardsville,

Southern Illinois University Press, 1991), p. 307.

[12] Ibid., p. 317.

[13] Ibid., p. 315.

[14] Ibid., p. 314.

[15] Cited in Trotsky, Great Lives Observed, edited by Irving H. Smith (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1973), p. 86.

[16] “On the Nature of the USSR,” in In Defence of Marxism (London: New Park, 1971), p. 39.

[17] “Dewey in Mexico,” in Reflections at Fifty (New York: The Vanguard Press, 1954), pp. 108-09.

[18] Ibid., pp. 111-12.

David North visited Trotsky’s final residence during his exile (1929-33) on the island of Prinkipo, and paid tribute to the life of the great theorist of world socialist revolution.