The Saville Report into Bloody Sunday in Londonderry, Northern Ireland, on January 30, 1972, maintains the cover-up of one of the most infamous massacres ever perpetrated by British imperialism.

Even after the passage of 38 years, the truth—that the murder of 14 unarmed civil rights protesters was carried out under orders from the Conservative government of Edward Heath and the army top brass—is denied.

British troops during the occupation of Northern Ireland

British troops during the occupation of Northern IrelandThe report, released Tuesday, continues the whitewash that first began immediately after soldiers from the 1st Parachute Regiment perpetrated their crime. In the face of overwhelming evidence, the Saville Inquiry is forced now to accept that none of those shot by soldiers “was armed with a firearm” or posed “any threat of causing death or serious injury”, and that, “In no case was any warning given before soldiers opened fire”.

It also concedes that claims soldiers responded to IRA gunfire are false. A soldier fired first, with other soldiers supposedly “losing their self-control and firing themselves, forgetting or ignoring their instructions and training”.

But this claim that soldiers lost control is meant to exonerate the military and political elite from charges that Bloody Sunday resulted from the preceding adoption of a shoot-to-kill policy that was approved by the British Tory government in power at the time.

The report claims, “In the months before Bloody Sunday, genuine and serious attempts were being made at the highest level [of the British government] to work towards a peaceful political settlement in Northern Ireland.

“Any action involving the use, or likely use, of unwarranted lethal force against nationalists on the occasion of the march (or otherwise) would have been entirely counterproductive to the plans for a peaceful settlement; and was neither contemplated nor foreseen by the United Kingdom Government”.

“We found no evidence of such toleration or encouragement” of the use of lethal force, the report adds.

An estimated 50,000 people attended the march in Derry, organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), demanding an end to anti-Catholic discrimination in the North. The ensuing killings were a turning point in the development of “The Troubles”.

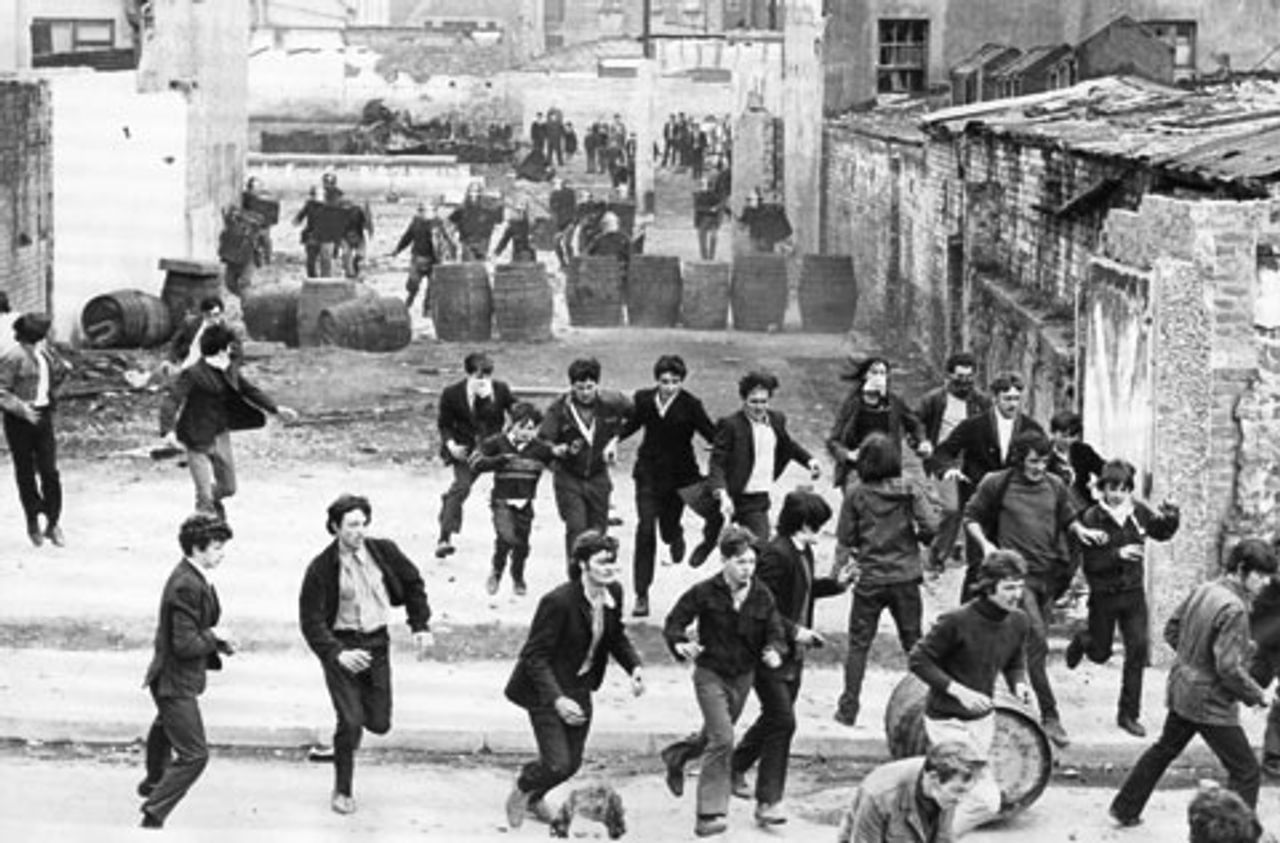

A skirmish between Irish youth fighting with stones and British paratroopers

A skirmish between Irish youth fighting with stones and British paratroopersIt led to the imposition of direct rule from London and helped drive broader sections of the Catholic working class behind the IRA and consolidate the bitter sectarian divisions that gave rise to three decades of civil war.

An April 1972 inquiry into Bloody Sunday by former Lieutenant-Colonel Lord Widgery was a naked cover-up. It found that the soldiers had shot in self-defence, having been fired on first, and claimed to have produced forensic evidence that those protesters who were shot had handled firearms. Widgery said there would have been no deaths if there had not been an “illegal march”.

It was only in order to secure the support of Sinn Fein for the May 1998 Good Friday Agreement, aimed at ending paramilitary conflict in Northern Ireland, that, in January 2000, the British Labour government acceded to the demand for a fresh inquiry headed by Lord Saville and two judges from Commonwealth countries. Then-Prime Minister Tony Blair made clear that its purpose was “not to accuse individuals or institutions, or to invite fresh recriminations…. Our concern now is simply to establish the truth and to close this painful chapter once and for all”.

Proceedings opened in March that year after nearly two years of investigations. The final witness was heard in January 2005. In total, 2,500 statements were taken and 922 people were called to give direct evidence. The inquiry also considered 160 volumes of evidence, 121 audio tapes and 110 video tapes.

The report of the inquiry, chaired by Mark Saville, a senior British judge, was originally scheduled for publication in 2005. It was repeatedly postponed and there was clear evidence of a cover-up throughout.

In July 1999, the High Court rejected an appeal that the identities of 17 paratroopers who fired their guns on the day of Bloody Sunday should be revealed, and hundreds more soldiers were granted the same anonymity.

In February 2000, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) admitted that it had destroyed two of the five remaining rifles used by the British Army on Bloody Sunday. Of the 29 rifles that may have been fired, 14 were destroyed by the MoD and 10 were sold. Large parts of MI5 (secret service) and British army documents made available to the inquiry were redacted, and critical documents made the subject of public interest immunity certificates—signed by government ministers and the MoD—preventing them being disclosed.

Despite these limitations, the material presented to the inquiry was damning.

The forensic scientist who carried out the original tests said to have shown that some of the demonstrators shot by British soldiers had handled firearms said he was wrong. John Martin acknowledged that the lead deposits found on several of the victims' hands could have come from other sources—including emissions from car exhausts.

Independent experts appointed by the Saville Inquiry described the evidence presented to the Widgery inquiry as “worthless”. Evidence was also heard that a nail bomb was planted on one of the victims, Gerald Donaghey, but this was rejected by Saville.

Eye-witness testimony made clear that those shot were unarmed, with one of the victims, Jim Wray, 22, lying on the ground when he was shot twice. The bullets hit him from just one metre away, a deliberate act of murder. Barney McGuigan, a 41-year-old father of six, was shot in the head with an illegal “dumdum” bullet, which fragments on impact.

However, much of the evidence presented has been ignored in order to arrive at the inquiry’s findings, particularly relating to the “shoot-to-kill” policy drawn up in preparation for the demonstration.

A top-secret communication in October 1971 from the head of the army, General Michael Carver, to Prime Minister Heath suggested it might be necessary to go into the predominantly Catholic Bogside district to “root out the terrorists and hooligans”.

A confidential memorandum from Gen. Sir Robert Ford, commander of land forces in Northern Ireland, to his superior, Gen. Sir Harry Tuzo, expressed concern at the number of no-go areas that the army was prevented from entering by pro-Republican youth, the Derry Young Hooligans (DYH). He wrote, “I am coming to the conclusion that the minimum force necessary to achieve a restoration of law and order is to shoot selected ringleaders amongst the DYH, after clear warnings have been issued”.

On December 14, 1971, a British Cabinet committee on Northern Ireland was addressed by General Ford, who outlined a deliberate policy of provocation focusing on stopping a scheduled march by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association. Ford had discussed issuing soldiers with rifles adapted to fire .22 rounds “to enable ringleaders to be engaged with this less lethal ammunition”. Thirty of the rifles were sent for “zeroing and familiarisation” training. Ford stated that “we would have to accept the possibility that .22 rounds may be lethal”.

Ford noted in a statement to the inquiry that there was a meeting at 10 Downing Street on 27 January, 1972, in which plans to suppress the march were discussed. On the same day, a document by Colonel Dalzell-Payne was circulating in the Ministry of Defence (MoD), warning that “disperse or we fire” methods would have to be used against demonstrators. Ford also pointed to a 19 April, 1972, statement to the House of Commons in which Heath admitted that the plan prepared to confront the march had been known to ministers.

A memo to the commander of 8 Brigade told them to “prepare a plan over this weekend”, taking into account “the likelihood of some sort of battle”. Witnesses John Roddy and Charles McDaid told the inquiry how they had received warnings from a friendly soldier and a telephonist at the Royal Ulster Constabulary’s (RUC) headquarters in Derry to stay away from the civil rights march because the paratroopers were “coming in shooting” and would “kill people”.

Witness 027, a soldier placed in a witness protection programme after receiving death threats, told how the night before Bloody Sunday groups of paratroopers boasted about how they expected to get “kills”. When they arrived in Derry, one paratrooper leapt out of the armoured vehicle and started firing immediately at some 40 civilians “running in an effort to get away. [Soldier] H fired from the hip…at a range of 20 yards. The bullet passed through one man and into another and they both fell, one dead and one wounded…. He then moved forward and fired again, killing the wounded man. They lay sprawled together, half on the pavement and half in the gutter. [Soldier E] shot another man at the entrance of the park, who also fell on the pavement”.

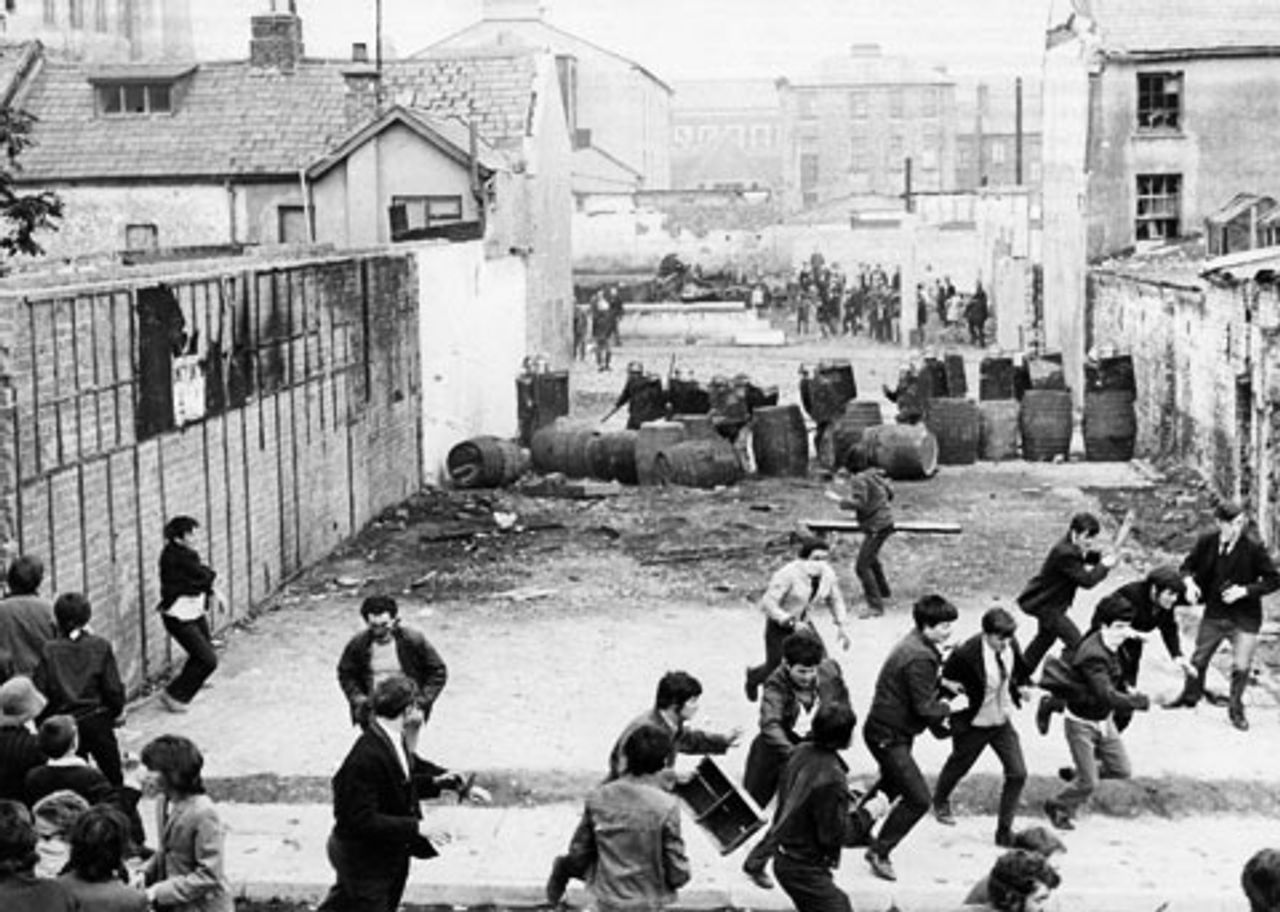

Youth running away from British troops in the Bogside area of Derry, Northern Ireland, where the massacre took place

Youth running away from British troops in the Bogside area of Derry, Northern Ireland, where the massacre took placeWhen the soldiers had arrived, the demonstrators had “stopped immediately in their tracks, turned to face us and raised their hands. This is the way they were standing when they were shot”.

Alongside the Army command and the Conservatives, the Labour Party bears direct responsibility for what happened on Bloody Sunday. Three years earlier, in 1969, the government of Harold Wilson had sent the British Army to Northern Ireland, claiming this was to defend the Catholic minority against a campaign of sectarian attacks and assassinations by Protestant Loyalist gangs.

In reality, the sending in of troops was part of an escalating campaign of repression by the British state, directed against the nationalist parties such as the Official IRA and the breakaway Provisional IRA, the civil rights movement and, ultimately, the political ferment and anti-imperialist sentiment within the Irish working class.

In August 1971, the Northern Ireland government introduced legislation under the Special Powers Act that provided for internment without trial. Mass arrests began, and by mid-January 1972 there were over 600 internees.

The brutal response of the British bourgeoisie in Northern Ireland was conditioned by their fear of an emerging challenge to their rule, not just in the north, but throughout the UK. The explosive development of the civil rights struggle coincided with the first national miners’ strike in Britain since the 1926 General Strike.

This was the beginning of an escalating wave of struggles that culminated with the bringing down of the Heath government by a second miners’ strike in 1974. Against a background of major social and political upheavals throughout Europe, the ruling elite viewed Ireland as a testing ground for measures they believed would be required in order to deal with a potentially revolutionary challenge by the working class—one that was ultimately averted only by the combined betrayals of the Labour and trade union bureaucracy and their political apologists.

Fill out the form to be contacted by someone from the WSWS in your area about getting involved.