Leonard Bernstein: The Political Life of an American Musician, by Barry Seldes, University of California Press, 276 pp.

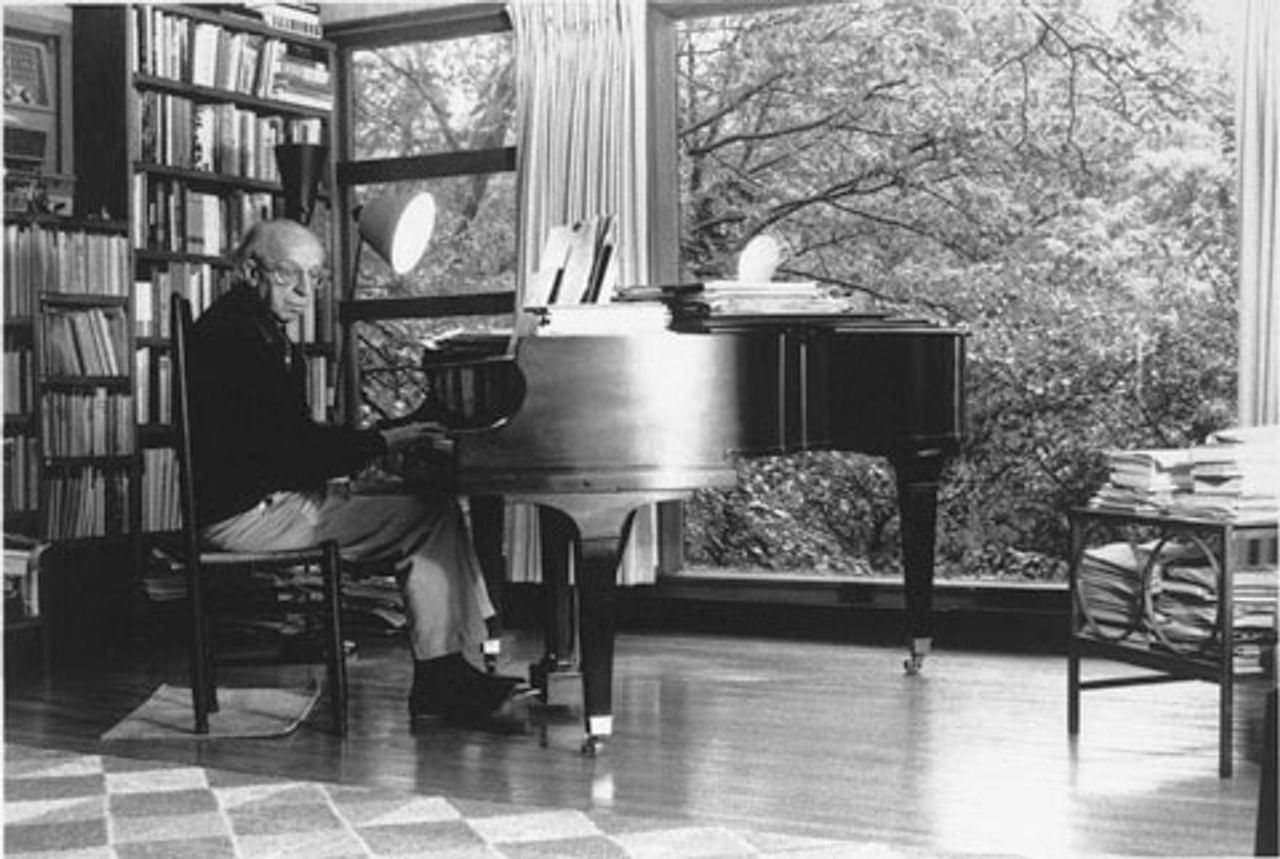

Leonard Bernstein in 1971

Leonard Bernstein in 1971Twenty years after his death, interest in the career of Leonard Bernstein shows no sign of flagging. The world-famous composer, conductor, pianist and educator has already been the subject of a number of full-length biographies, and another one might seem redundant. However, the recent book by Barry Seldes adds something important to the study of Bernstein’s life and work. Seldes, a professor at Ryder University in New Jersey, is the first of his biographers to have studied the composer’s massive FBI dossier.

Many may have heard the story of how Bernstein achieved overnight fame in November 1943, when he was called on to substitute as conductor of the New York Philharmonic for an ailing Bruno Walter, in a concert broadcast nationwide by CBS. The 25-year-old took the music world by storm. The widely accepted version of his career has Bernstein going from one success to another over the next few decades.

Bernstein in 1945

Bernstein in 1945In the 1940s and 50s, Bernstein composed some of his best known works, including the ballet Fancy Free, and, for the musical theater, On the Town, Wonderful Town, Candide and West Side Story. This was followed by the flowering of his conducting career at the New York Philharmonic between 1958 and 1969. During this same period (1958 to 1972) he also addressed a huge audience as the host of the legendary Young Peoples Concerts on public television. Millions of viewers were introduced to classical music through Bernstein’s path-breaking work.

As Seldes shows, however, Bernstein’s success hardly followed a straight line. By the time he was in his early 30s, long before he accomplished most of what he is now remembered for, he was blacklisted by the US State Department and the CBS radio and television network. For several years his career was derailed and threatened with the kind of disaster that befell other artists in that period, from Paul Robeson to John Garfield. FBI surveillance of Bernstein, which began before he was 21 years old, continued for decades.

Most of Bernstein’s audience and those who admire him today do not realize that, in the words of his longtime publicist, “Lenny was a socialist.” As Seldes explains: “I dispel the idea that Bernstein was apolitical or only occasionally political … One comes to see that his political commitments and activities were highly important to him, that he was victimized because of them, and that they often played a significant role in his artistic career.”

Aaron Copland

Aaron CoplandThe author does not ignore other salient aspects of Bernstein’s life, including his homosexuality, which was widely known but not publicly acknowledged by the composer-conductor until he was in his 50s. Seldes warns, however, that readers looking for “who slept with whom … will be disappointed in this work.” He correctly insists that the personal and psychological cannot be separated from and elevated above the social and historical factors that helped shape the composer’s life. Especially in the case of Bernstein, who was politically engaged from the time he was a teenager, his work and career cannot possibly be understood in any other framework.

The young Bernstein, born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, entered Harvard University in 1935. A musical prodigy, he soon met and impressed composer Aaron Copland and Serge Koussevitsky, the Russian-born conductor of the Boston Symphony.

Serge Koussavitsky

Serge KoussavitskyDuring this very same period, Bernstein was radicalized by the great events of the 1930s. Far from ignoring politics in the interests of his musical career, he plunged into both worlds at the same time.

Like many other young people, artists and intellectuals, Bernstein looked to the Soviet Union as a bulwark in the fight against Hitler. Unable to distinguish between the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the counterrevolutionary regime headed by Stalin that claimed to represent socialism, many talented and sincere individuals were encouraged by the American Communist Party to support the New Deal of Franklin Roosevelt. These were the years of the Popular Front, when Stalinism used the danger of fascism to subordinate the working class to liberalism.

During World War II, when the US and USSR were allies, Bernstein appeared with Robeson and became involved with the National Council of American-Soviet Friendship. After the war, as the Cold War witchhunt began, he came to the defense of the Hollywood Ten, the screenwriters subpoenaed and later jailed for contempt, and campaigned for third-party presidential candidate Henry Wallace, the former vice president under Roosevelt who symbolized the hopes for a continuation of the Popular Front.

Bernstein would pay a heavy price for this political activity. In 1950 he was formally identified as a subversive in the notorious anticommunist periodicals Counterattack and Red Channels. He was soon blacklisted by CBS, the network whose radio broadcast had first brought him fame. For the next three years he lived in fear of being called to testify before the witchhunting committees of the US House or Senate in Washington. Although he was not called, he was forced in 1953 to submit a lengthy and humiliating affidavit, confessing to various errors in his past political associations and swearing his loyalty to the US in the Cold War, in order to secure the renewal of his passport.

Ethel and Julius Rosenberg

Ethel and Julius RosenbergThis was in the summer of 1953, only weeks after the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg on charges of conspiracy to commit espionage for the USSR. Senator Joseph McCarthy was at the peak of his power and the witchhunt had reached a fever pitch. Although Bernstein probably had no knowledge of it at the time, under the police-state McCarran Act his name had been placed on the list for preventive detention in event of a “national emergency.”

Bernstein got his passport, and was soon removed from the CBS blacklist. By 1956 he was engaged as a guest conductor at the New York Philharmonic under his old mentor Dmitri Mitropoulos, and soon thereafter was named its music director. Within a few short years he had achieved the summit of musical eminence in New York. In 1959, at groundbreaking ceremonies for the Lincoln Center arts complex in New York City, Bernstein greeted President Dwight Eisenhower.

Bernstein’s progress as a conductor went hand in hand with huge success as a composer. In late 1956 Candide, his operetta based on Voltaire, opened on Broadway. Although the work went through numerous revisions over the years and has its critics, most are agreed that its music is sublime, one of Bernstein’s most remarkable creations.

West Side Story

West Side StoryLess than a year later West Side Story opened in New York and immediately became an unalloyed smash hit. As Seldes suggests, in some respects the Philharmonic was almost obliged to hire Bernstein as music director. Here was a musician who had attracted a huge popular following while having his feet still firmly planted in the classical music world.

At the same time, Bernstein could never forget the cost of his success. He was one of the relatively few whose brush with the blacklist had had a “happy” ending. He was well aware of the many for whom the purges had meant the end of their careers and in a few cases even of their lives.

It is clear that Bernstein felt the sting of the self-abasement represented by the 1953 affidavit. Although he hadn’t “named names” and the affidavit was not publicized, he had repudiated his political past. The document was circulated widely in anticommunist circles and could be used against him at any time. This was a particularly painful experience for Bernstein precisely because, unlike Elia Kazan and others, he had nothing but hatred and contempt for the witchhunters.

FBI intrigues and other attacks on Bernstein continued into the 1970s, especially after he resumed political activity, both in the civil rights struggle and the movement against the Vietnam War. When Bernstein and his wife Felicia Monteleagre hosted a legal fundraiser for the Black Panther Party in their home in early 1970, the New York Times denounced him for “elegant slumming.”

A few months later Tom Wolfe, the mediocre practitioner of “New Journalism” who later became an admirer of George W. Bush, published his infamous attack on “radical chic.” Bernstein’s political detractors had a field day, and the FBI took advantage of the incident to send out phony letters to Bernstein and others, signed “A Concerned and Loyal Jew,” and pointing to the Panthers’ alleged anti-Semitism.

Seldes’ account of the harassment of Bernstein is obviously important for what it shows about the scope and persistence of the state attacks on democratic rights, echoed in today’s campaign to intimidate principled opponents of war crimes in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere. The FBI especially feared Bernstein because he was such a popular and widely beloved artist.

Missing in this volume, however, is a deeper appreciation of how unprepared Bernstein was for the political shifts that took place in the postwar period. Like many others of his generation, he was under the illusion that the Second World War was a war for democracy as advertised, an illusion that was assiduously fostered by the Communist Party and the great bulk of the American Left of that time.

When the war was followed by the Cold War, the rise of McCarthyism and the wholesale betrayal by American liberalism of the principles it claimed to defend, Bernstein―along with many others―was stunned and demoralized. Without grasping the historical position of US imperialism, now the dominant power, and its immense contradictions, as well as the role of the Democratic Party as one of its leading political agencies, he could not understand that beneath the surface of the witchhunt and 1950s prosperity new struggles and crises were being prepared.

Bernstein was undoubtedly angered by the strangulation of the labor movement and the degeneration of liberalism, but apparently he hoped for a second coming of the political alliances he had known as a young man. Seldes, with his own rather uncritical description of the Roosevelt years, does not explore this issue.

There is yet another important and complex side to Bernstein’s life and career that Seldes discusses as well--the relationship between Bernstein’s political disappointments and the inability of the composer to produce the “great work” that he often spoke of. The author notes Bernstein’s longstanding attempt to develop as a composer beyond his important achievements in the musical theater. He sought to compose a masterwork, if possible in the operatic field.

Why was Bernstein unable to create the masterwork that he often spoke of? In Seldes’ estimation, Bernstein sought a way to give musical expression to “matters close to him--not least the crises in liberalism’s acquiescence in the neo-imperialism of the Johnson era, its fragmentation during the 1970s, and its increasing irrelevance, and loss of dignity and millions of adherents in the 1980s.” It is significant that Seldes is sensitive to these issues.

These ideological and historical dilemmas meant, according to Seldes, that Bernstein was stymied when it came to finding a libretto or programmatic narrative for the kind of work he had in mind, and also that he lacked the audience that would provide him with the inspiration he required.

Consideration of this subject requires some examination of Bernstein’s musical history and aesthetic outlook, and Seldes’ treatment of this is another virtue of his book.

Bernstein was a highly unusual figure. To characterize him merely as a composer, conductor, pianist and educator fails to do him justice. He was someone who thought and felt deeply about the role of culture in society, the relationship between music and social life, and the role of music and culture as an index of and a force for human progress. This was bound up with his passionate defense of democratic rights and his sympathy for the ideals of socialism.

Bernstein plunged into debates over the future of music from his earliest years as a student and apprentice conductor. He was associated with the defense of tonality after it had gone out of fashion in certain musical circles in post-World War II America. In his famous Norton Lectures at Harvard in 1973, he spelled out in some detail his views on this subject, rejecting the dogma of atonality that then held sway in university music departments and among many critics.

One of the most prominent defenders of atonality was Theodor Adorno, the German philosopher, sociologist and musicologist, a leading member of the Frankfurt School of anti-Marxists. Adorno had been a pupil of the remarkable composer Alban Berg, who in turn was the most famous student of Arnold Schoenberg.

Theodor Adorno

Theodor AdornoA detailed discussion of Adorno’s work is far beyond the scope of this review, but in connection with Bernstein’s views and his music a few points are in order. Bernstein termed Adorno’s The Philosophy of Modern Music “a fascinating, nasty, turgid book,” and he had good grounds for this hostility.

As Seldes summarizes Adorno’s views, “Tonality functions as political orthodoxy: it forces the composer into closure and reconciliation―that is, into a false ideology that affirms the legitimacy of the status quo and that is fed to the mass audiences of repressed subjects by the culture industry. Atonality is thus the weapon of resistance.”

According to Adorno, the tonal music that had been composed for hundreds of years was a product of the epoch of bourgeois liberalism, and had now become “totalitarian.” This ahistorical and mechanical conception, anticipating reactionary positions later elaborated by certain postmodernist critics, places an equal sign between the ruling class and its trajectory, on the one hand, and the development of music, on the other.

It is in essence the Stalinist doctrine of “socialist realism” turned inside out. Whereas the Stalinists insisted that music had to be immediately accessible and “uplifting,” Adorno called for music that, in Seldes’ words, “would be unrecognizable to anyone but composers and cognoscenti.”

Bernstein fiercely opposed this dogma, insisting above all that music required what Seldes refers to as a “communally engaged audience.” While of course this did not mean one never challenged one’s audience, a composer unable or uninterested in reaching such an audience was a contradiction in terms.

This gives us a clearer general conception of Bernstein’s aesthetic approach. However, it was one thing to argue against the uncritical advocates of atonality and another to show the way forward in composition itself. This proved a formidable challenge.

Seldes is correct in pointing to the socio-political sources of Bernstein’s perplexity and ultimate discouragement, but his treatment of the topic is rather narrow. The author’s suggestion that a more congenial political atmosphere would have solved Bernstein’s compositional problems somewhat oversimplifies the matter.

The relationship between Bernstein’s politics and his musical genius is a complex question that cannot be reduced to a simple equation between his progressive social views and his musical output. His music was the product of many influences, including his background as the child of Jewish immigrants, the cultural and political climate in which he matured, and the arduous, painful, conscious artistic and intellectual labor in which he engaged. Bernstein, as is well known, agonized over his compositions. He was often torn between immense self-confidence and self-doubt. There were many “progressive” musicians and composers in the middle of the 20th century, in other words, but not many Bernsteins.

One missing element in Seldes’ account, as wide-ranging and conscientious as it is, is the impact of the anticommunist witchhunt on culture as a whole. It is important to set the record straight on how Bernstein was victimized, but this was not something that merely affected him, or even the sum total of the individuals who immediately suffered. The virtual criminalization of left-wing thought in the US inflicted broad damage on the cultural climate and development of the country--in film, literature, music, art and elsewhere--that has not been overcome to this day.

Given the nature of Bernstein’s personality, his political principles and his aesthetic outlook, the postwar reaction could not help but prove a hindrance to his creative life and artistic enthusiasm. Despite these problems, he left behind a dizzying combination of achievements on many different levels. His legacy is one of struggle and engagement that will serve as an example for others who are sure to follow him. Seldes’ work is a valuable contribution to understanding that legacy.