Less than three weeks before 29 miners were killed in an explosion and fire ball at the Upper Big Branch mine last April a government safety expert tried to get top Massey executives to send the company’s ventilation expert to fix ongoing ventilation problems at the mine.

The attempt was made by Mine Safety and Health Administration ventilation supervisor Joseph Mackowiak at MSHA’s District 4 office in Mount Hope, West Virginia, and is documented in a series of emails obtained and disclosed last Thursday by the West Virginian Charleston Gazette. MSHA officials had kept the correspondence private.

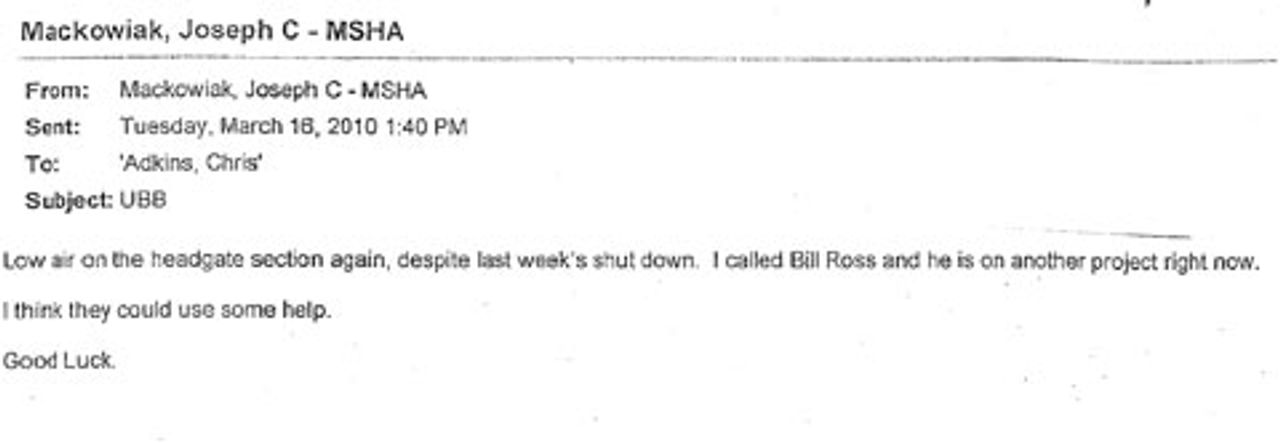

On March 16, 2010, 20 days before the UBB disaster, Mackowiak wrote to Massey Vice President Chris Adkins:

“Low air on the headgate section again, despite last week’s shut down. I called Bill Ross, and he is on another project right now.

“Low air on the headgate section again, despite last week’s shut down. I called Bill Ross, and he is on another project right now.

“I think they could use some help.

“Good luck.”

Bill Ross used to work for MSHA as the ventilation supervisor until he retired and went to work for Massey as a ventilation specialist.

Records show that Adkins never responded to Mackowiak’s request.

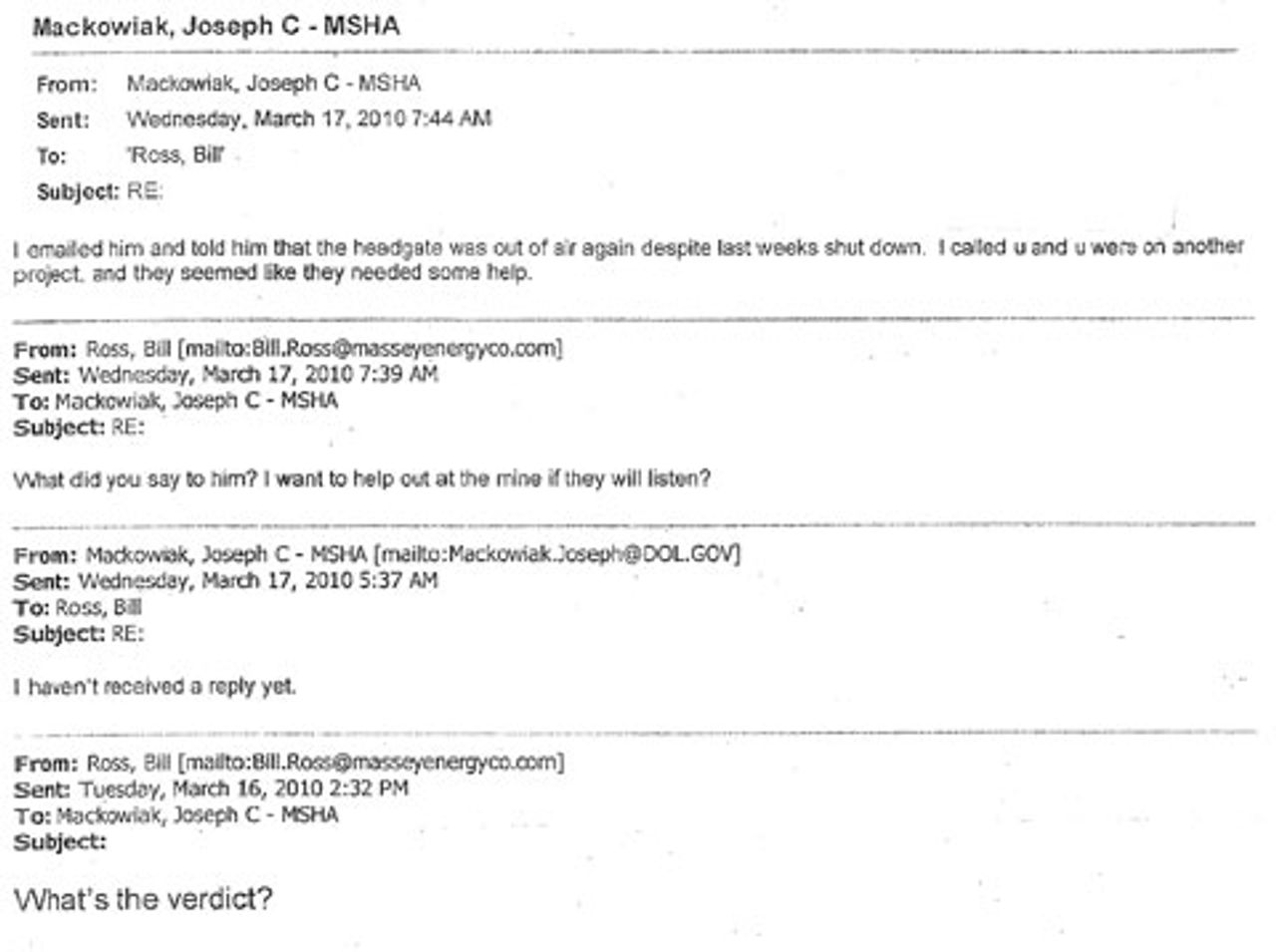

About an hour after Mackowiak’s email to Adkins, Ross sent an email to Mackowiak asking, “What’s the verdict?”

“I haven’t received a reply yet,” Mackowiak answered early the next morning.

“I haven’t received a reply yet,” Mackowiak answered early the next morning.

In another email sent two hours later, Ross asked, “What did you say to him? I want to help out at the mine if they will listen?”

Mackowiak responded a few minutes later, “I emailed him and told him that the headgate was out of air again despite last week’s shut down. I called u and u were on another project, and they seemed like they needed some help.”

Mackowiak testified about this exchange to MSHA officials investigating the explosion, but those transcripts have yet to be made public. Both Adkins and Ross are among the 18 Massey officials who have refused to testify to state and federal investigators.

Mackowiak did not site Massey at the time, even though low airflow is a violation of safety regulations. Mackowiak could have ordered that section of the mine closed and the workers withdrawn until the problem was corrected.

The longwall face is 1,000 yards long. The longwall mining machine cuts back and forth along a set of railroad tracks that run alongside the mine face. As coal is mined, methane gas is released that must be vented out of the mine.

It is believed that a pocket of methane gas was ignited by sparks coming off of the longwall machine and burnt for 60 to 90 seconds before igniting a monstrous secondary coal dust explosion. The blast tore through miles of underground tunnels, killing both the miners working the longwall section as well as miners working other sections of the mine.

It has already been reported that a water system on the longwall mine was not working at the time of the explosion. The water system is designed to keep the drill bits cool and prevent sparks from igniting methane gas.

One week before the emails were written, an MSHA inspector found the airflow going in the wrong direction. The week before that, an MSHA inspector found the airflow was half of what was required under the company’s own ventilation plan.

Notes written by the MSHA inspector at the March 2, 2010, inspection said that the problem should have been obvious to mine management.

“I believe the foremen in this section have showed high negligence by not reporting/correcting ventilation problems that were obvious to me and the men on [the] section,” the inspector wrote.

The UBB mine had continuous problems with ventilation and received scores of citations for violating the company’s ventilation plan along with hundreds of other violations, including allowing coal dust to build up.

Yet despite this record, MSHA officials never took steps to close the mine and force the company to resolve the problems.

In fact, in August 2009, MSHA approved a ventilation plan that reduced the amount of air flowing to the longwall face from 60,000 cubic feet per minute to 40,000. Federal regulations require a minimum of 30,000 CFM, but officials can require more in case-by-case situations.

Twenty minutes before the blast, the airflow reaching the longwall was recorded as 56,000 cubic feet per minute above the amount required in the plan. However investigators are looking into why, on average, readings at the longwall fell from over 100,000 CFM to around 50,000 CFM in the month before the blast. It is very likely that Massey, which was developing a third area of the mine for mining, was diverting air to that area from the working longwall section.

Subscribe to the IWA-RFC Newsletter

Get email updates on workers’ struggles and a global perspective from the International Workers Alliance of Rank-and-File Committees.