This is the first of a series of articles devoted to the recent Toronto film festival (September 6-16).

“The artist must not only have looked around at much in the world and made himself acquainted with its outer and inner manifestations, but he must have drawn much, and much that is great, into his own soul; his heart must have been deeply gripped and moved thereby; he must have done and lived through much before he can develop the true depths of life into concrete manifestations.” —Hegel

The Toronto International Film Festival screened some 372 films this year, including 289 features, from 72 countries. This year’s festival and the general state of the film world present a sharper contradiction than ever.

On the one hand, the major productions of the American film studios, which dominate the world market, are more and more negligible, often painfully so. The summer and this fall so far have been especially miserable.

In the midst of the Toronto festival, the trade publication Variety carried the news that US box office returns for the weekend of September 7-9 were the lowest in more than a decade, since, in fact, shortly after the attacks of September 11, 2001. Variety commented, “The severe lack of interest in moviegoing this weekend is causing concern in Hollywood.” Another business journal termed the figures “scary.”

Overseas results were also weak, as Dark Knight Rises “fell a staggering 74 percent from last weekend,” principally due to a 60 percent decline in China, while The Amazing Spider-Man “fell even further” in China, by 73 percent.

One could only congratulate the American and global public on its taste. The state of the economy is, of course, a significant factor, but the film industry, in the words of one studio executive, is hardly giving moviegoers “a reason to leave the house.” There is virtually nothing in the theaters that could arouse interest or satisfy elementary human needs. In the end, even the virtual monopoly that Hollywood enjoys over the world’s movie screens and the vast advertising and propaganda machinery at its disposal cannot induce audiences to flock to films that are neither intriguing, genuinely exciting nor enlightening.

And this latter category includes a section of the larger-budget studio or “independent” films presented in Toronto, which are no more enticing than those appearing at local cinemas. Triviality, self-involvement and social indifference dominate official film industry and film festival circles.

On the other hand, an initial list of films that seemed worth seeing in Toronto included more than 80 titles, an unprecedented number. We succeeded in viewing nearly 50 of those. And, while there were disappointments and obvious failures, the level of seriousness and honesty seemed to us higher than at any such event in memory. Several dozen films fell into the general category of the thoughtful and socially critical.

Certain features of the present situation, especially the conditions that have emerged since the financial collapse of September 2008, are making themselves felt. One notices a marked shift in attitude. It is now widely taken for granted that the very rich—and even upper middle class layers—are odious, grasping and destructive, selfish and cruel, capable of almost any infamous act (Capital from Costa-Gavras, Shanghai from India, etc). Perhaps most tellingly, this finds reflection too in American filmmaking, even in relatively slight works or those not expressly addressing social issues (What Maisie Knew, The Brass Teapot, Artifact).

At the core of this phenomenon, for surely the films and filmmakers lag behind social development, lies a considerable radicalization in popular consciousness. Suddenly, “everyone” feels an abhorrence for bankers, Wall Street speculators and corporate directors, the heroes of the 1980s and 1990s. Suddenly, “everyone” knows that the present social structures and conditions, which spelled the “end of history” two decades ago, are unfair, unequal and only growing worse.

While filmmaking as a whole still only palely reflects the present-day world, it is to the credit of numerous directors, writers and producers that we saw images in Toronto this year, in both documentary and fiction, of some of the most oppressed people on earth, human beings who normally have no presence or voice whatsoever: in Kabul, children collecting cardboard for a few coins and a bite to eat (Far From Afghanistan); in a remote Chinese village, peasants living under terribly primitive conditions (Three Sisters); poor kids on the streets of Mumbai and Port-au-Prince (Mumbai’s King, Three Kids); victims of social misery and despair in Côte d'Ivoire and Guatemala (Burn It Up Djassa, Dust); prostitutes in Maputo, Mozambique (Virgin Margarida).

Far from Afghanistan

Far from AfghanistanThe crimes of imperialism too are taken note of, in Far From Afghanistan (the US invasion and occupation), Fidaï and Zabana! (which both treat the depredations of the French military during the Algerian Revolution) and A World Not Ours (the oppression of the Palestinian people), along with counter-revolutionary violence in Indonesia (The Act of Killing) and Argentina (Clandestine Childhood), social injustice in the US (The Central Park Five) and China (When Night Falls), and the specific problems of the young and excluded (The We and the I from the US, Juvenile Offender from South Korea).

The continuing difficulties in filmmaking are very real too. They are both social and artistic, and, in fact, those sets of problems are related.

In Toronto we saw several dozen films that were interesting, intelligent and, for the most part, incomplete and unsatisfying. Indeed, a certain sameness pervaded a good portion of the socially critical films. They tend to be a little flat, indistinct, rather somber and somewhat narrow in scope. They are, in general, what we have called “small bore” works.

Dormant Beauty

Dormant BeautyWhile watching a new version of Charles Dickens’ remarkable 1860-61 novel Great Expectations (directed by Mike Newell), it occurred to me how much filmmaking at present lacks the brilliant variety of human types and personalities that one comes across, for example, in Dickens, Shakespeare, Balzac, Scott and Shaw, or, for that matter, in Charlie Chaplin, John Ford, Orson Welles, Jean Renoir, Akira Kurosawa and Federico Fellini.

One longs for the distinct and vivid presence of a Joe Gargery, Herbert Pocket, Miss Havisham, Mr. Pumblechook, Abel Magwich, Biddy or Mr. Jaggers, all there in one of Dickens’ novels!

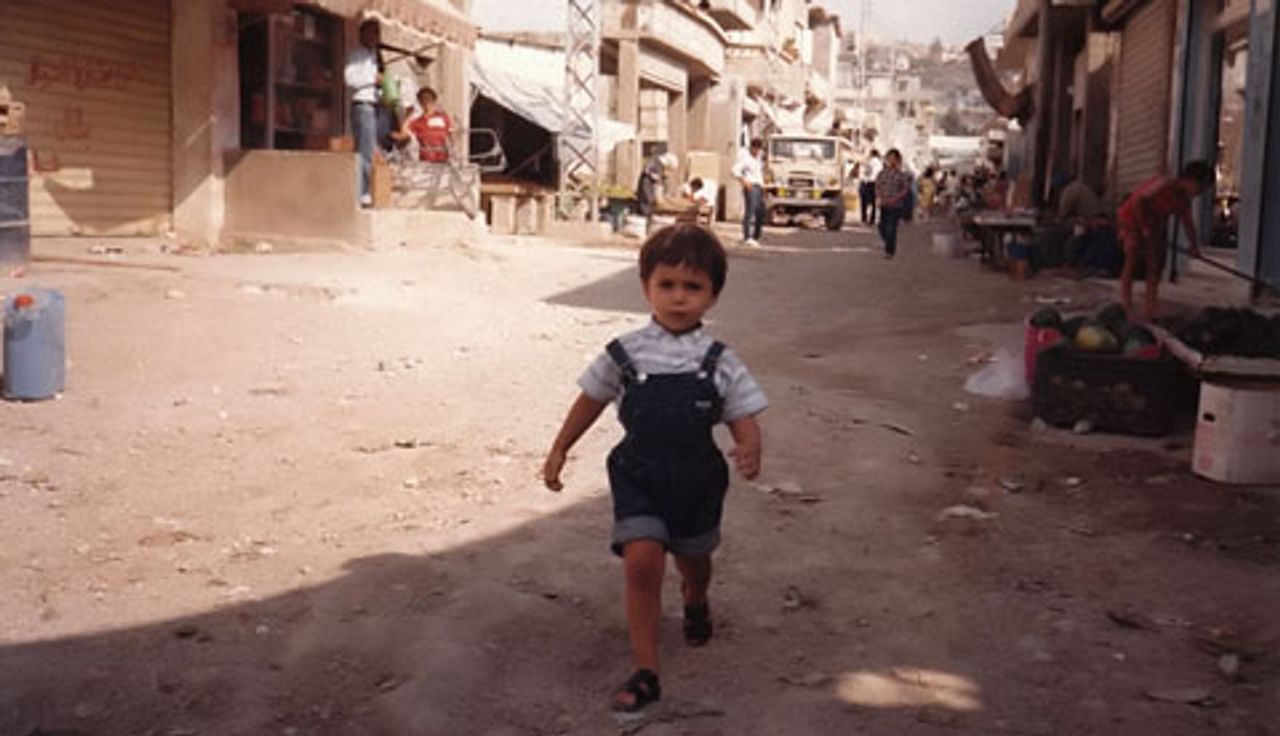

A World Not Ours

A World Not OursThe most complicated films in Toronto, A World Not Ours and Fidaï (although non-fiction), Dormant Beauty (from Marco Bellocchio, about a Terri Schiavo-type case in Italy in 2008-09), Underground (about a youthful Julian Assange), Far From Afghanistan (an uneven, but important film, which begins to connect imperialist war and the social crisis in America), The We and the I (which takes a group of minority youth from the Bronx seriously) and a few others stand out as exceptions. The personalities across these films add up to something.

Fidaï

FidaïMany other of the socially minded films, however, select an aspect of life and examine it seriously, but largely apart from, even indifferent to, the “soul” of society as a whole. We see the world as it is first or immediately experienced, as trees and not forest. But there are consequences to such self-limitation. If you weight your picture of life in China, or Guatemala, so as to exclude almost entirely the global whole, or treat brutal conditions in West Africa, or repression in Israel, as a national or local problem, the essential social and historical truth of these phenomena is not revealed. Ultimately, the picture must lose some of its color and vividness.

From one point of view, this problem can be seen as an inevitable phase. Emerging from a period of social reaction, in which many artists turned their back on the lives and fate of the mass of the population, the filmmakers today are almost bound to have difficulty in subjecting social life to the richest artistic presentation. They are, so to speak, “out of practice.” Undoubtedly, the best elements are being pushed forward by objective developments to greater depths.

The limited vision is not always innocent. In some cases, it either plays a retrograde social role, or threatens to. The insistence of As If We Were Catching a Cobra (directed by Hala Alabdalla) from Syria, for instance, a film about censorship and repression in both Egypt and Syria, on treating the situation in the region without a single reference to the role of the Great Powers is highly dubious. The work all too neatly suits Washington’s spurious “democratic” agenda.

The process is immensely complicated, but, in the final analysis, if a film’s form is deficient, this results from deficient substance and ideas. The deeper that the world and reality are grasped and assimilated, the greater is the possibility for beauty and elegance in presentation.

The shape, the form of an art work is not accidental, haphazard, stumbled upon, a “found” or external object, it is determined entirely by our intellectual-artistic interests, it exists solely for that purpose. It is the content made visible. The outer form points to the inner meaning and the art work as a whole points to something beyond itself, to important truth about our reality.

When society is not yet examined from top to bottom, when, to speak bluntly, a good deal of intellectual laziness and historical ignorance still persist, when the fate of broad layers of the population remains a rather abstract concern for most artists, it is no wonder that truly ground-breaking and gripping films are few and far between. We will go on in subsequent articles to discuss in more detail some of the interesting films.

To be continued