This is the second of a series of articles devoted to the recent Toronto film festival (September 6-16). Part 1 was posted September 22.

A World Not Ours

A World Not OursThe substantial number of films at the recent Toronto film festival that provided insight into our present complex reality points to the fact that many social and political processes have reached an advanced stage of development. The owl of wisdom, notoriously, flies late in the day.

Sufficient time has passed and sufficient understanding, even if of a limited character, has accumulated to the point that the important outlines of phenomena such as the Algerian revolution (1954-1962), decades of war in Afghanistan, repression in Central and South America, the 1965 massacre in Indonesia, national independence struggles in Africa, the persistence of poverty and social inequality in China and, for that matter, the decay of a city such as Detroit have begun to be grasped and made the basis for serious artistic representation.

A number of recent Palestinian and Israeli films reveal how the perception of that situation, both in terms of the deep dysfunction of Israeli society and the failure of Palestinian and Arab nationalism, has considerably deepened.

A World Not Ours

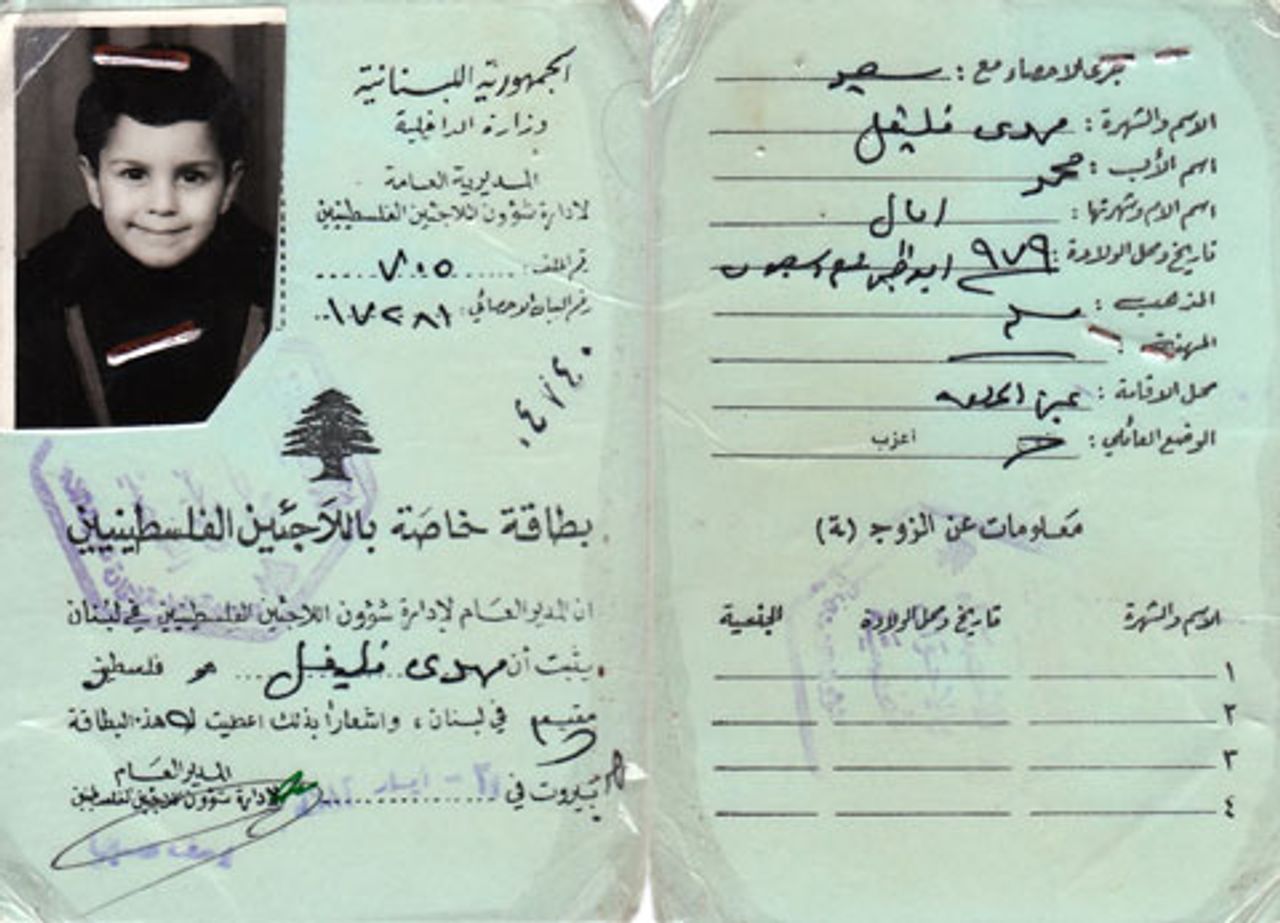

A World Not OursA World Not Ours, directed by Mahdi Fleifel, is a remarkable work, one of the most complex and impressive at the festival. Fleifel’s grandparents were driven out of their village by the Israelis in 1948, and eventually settled in the Ain El Hel-weh refugee camp in southern Lebanon. The future filmmaker was born in Dubai in 1979, where his father had moved for employment.

A World Not Ours (which takes its title from a novella by Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani, a member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine assassinated by the Israelis in July 1972) is both a personal memoir and a tracing out of the Palestinian condition.

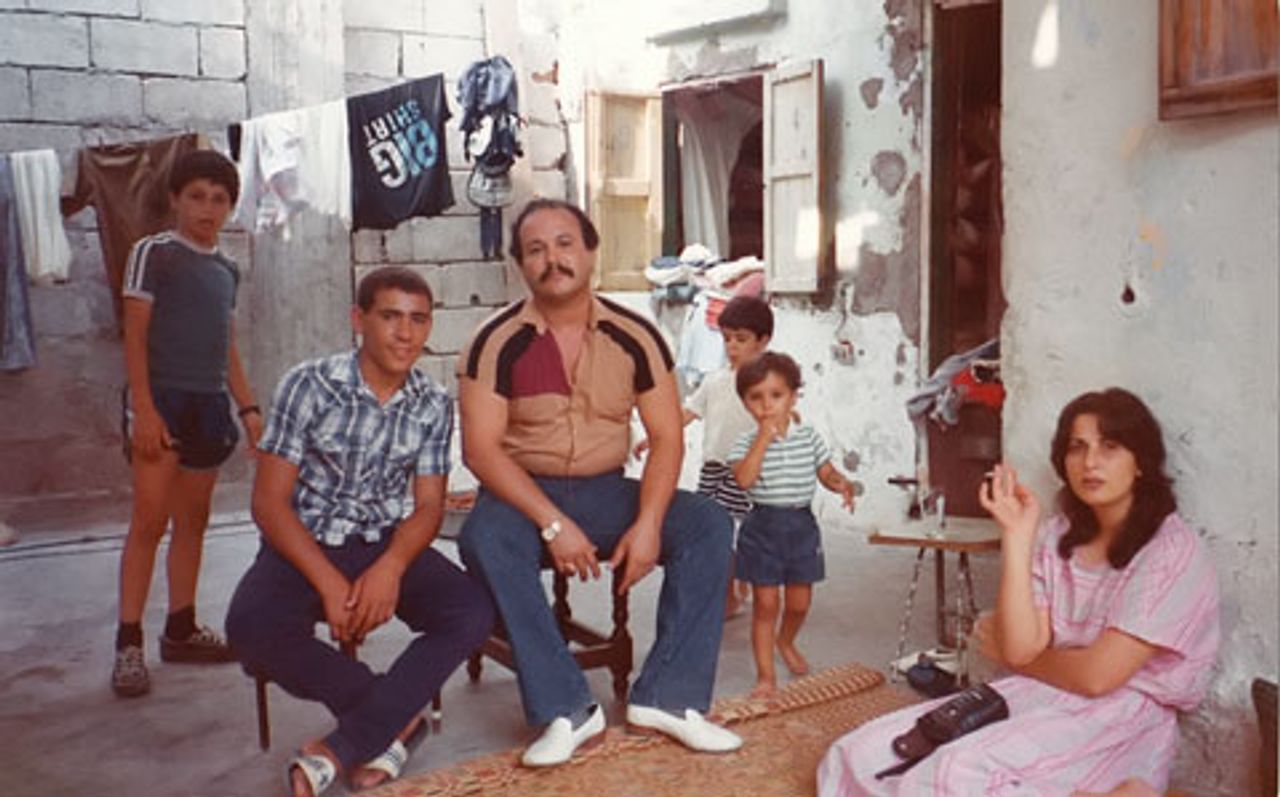

In a lively and even entertaining fashion, Fleifel recounts his family’s experience, the general experience of Ain El Hel-weh and the fate of three individuals in particular, his grandfather, his uncle Said (actually, his grandfather’s half-brother) and his good friend, Abu Iyad (named after the murdered PLO intelligence chief), a former Fatah fighter.

An enormous quantity of film and video footage shot by Fleifel’s father and the director himself, over the course of several decades, has been edited with great skill and sensitivity, to bring out some of the more essential truths. In the accompanying interview, Fleifel and co-producer Patrick Campbell discuss the issues involved in the film’s assembling.

An extraordinary objectivity, in the best sense, pervades even the most personal elements of the narrative. Without self-pity or self-aggrandizement, Fleifel presents his dilemmas and those of his family and friends so that they shed light on the Palestinian catastrophe as a whole. A strong sense of and for history pushes the film forward.

Fleifel contributes an engaging narration (he cites Woody Allen as an influence!) that honestly and disarmingly links the wide variety of images and events, including, for instance, the refugee camp youth cheering on their rival World Cup favorites (having no country of their own, each adopts Italy, Brazil or another contender as his own) and a wedding that will mean a local girl departing her family and friends for Germany, an event that heartbreakingly leaves the women sobbing. Snippets of seemingly unlikely popular music (including the melancholy sounds of Neil Young) underscore the global cultural sophistication at work.

Fleifel identifies his ambivalent relationship to Ain El Hel-weh, a place to which he went on holiday as a child, but which he was privileged to leave. The conflicted feelings perhaps find expression in both his father’s and his own commitment to recording life in the camp through their obsessive filming. It is a fascinating, throbbing, appalling place, a product of some of the worst traumas of the twentieth century, a continuing reminder of imperialist and Zionist barbarism and the rottenness of the Arab regimes, but also home, even if “on loan,” and at one time a center of human solidarity.

Toward the beginning of his film, Fleifel describes the establishment of the refugee camp, home to tens of thousands of expelled Palestinians who expected to return to their towns and villages. He notes calmly that 64 years later, “People are still waiting.”

In an interview included in the film’s production notes, Fleifel comments, “When I was making the film I came across a quote by David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister, who famously said about the dispossessed Palestinians that, one day ‘The old will die and the young will forget.’ Making this film for me has been a way of challenging that. Forgetting for us Palestinians would simply mean ceasing to exist. Our fight throughout history, and still today, is to remain visible. Making my film is a way of reinforcing and strengthening our collective memory.”

The three figures mentioned above emerge with considerable force and distinctness in A World Not Ours.

Fleifel’s grandfather, 16 at the time of the Palestinian exodus in 1948, continues to live in the refugee camp. Harassed by the noise and commotion of the neighborhood kids, increasingly unwell, the older man personifies the tragedy of his generation. Largely oblivious or hostile to the modern world, not understanding his grandson’s profession or outlook on life, Abu Osama, as the production notes indicate, “Since his wife passed away three years ago…has led a pretty quiet life, mostly living between the mosque and his home, where he prays, watches Al-Jazeera news, and mellows in the alleyway outside his front door.”

His much younger half-brother, Said, is a more tragic figure. He grew up in the shadow of his brother, Jamal, who was beloved in the camp for his military and community exploits. The latter was shot in the throat by a sniper in 1991 when the Lebanese military unsuccessfully attempted to take control of Ain El Hel-weh. After his heroic brother’s death, Said “was not the same,” the narrator explains.

Reduced to living in fairly wretched conditions, collecting and selling cans, trapped in the role of quasi-“village idiot,” Said tells the camera that he “can’t get married,” in fact, he “can hardly support” himself. He complains to the filmmaker, “Your uncles never helped me.” Said’s immediate family has not been kind to him, setting an example for the entire community. His face and body, movingly, are tortured by regret and failure and disappointment.

The politically most telling figure in the film is Abu Iyad, the former Fatah militant. By 2010, he has reached the point of making public denunciations of the Palestinian officialdom. Driven half-mad by the situation, he even heaps curses on the entire people. “We should all be massacred.” Referring to the Palestinian authority, Abu Iyad exclaims, “They screwed us up. No, we destroyed ourselves.” He denounces the “corrupt leaders” as “thieves.”

Abu Iyad’s father, a former Fatah officer, condemns Palestinian National Authority president Mahmoud Abbas as a “son of a bitch” who has appointed a “CIA agent” as head of the police in Ramallah. The anger and contempt pours out of the men, who have sacrificed everything for the Palestinian cause. Fleifel’s old friend bitterly describes his situation: “No future, no work, no education. No nothing.” Finally, he tells Mahdi that he has handed in his Fatah card, “I quit. I don’t give a shit.… It’s all over.”

Abu Iyad smuggles himself out of Lebanon and makes his way to Greece, only to be nabbed by police in Athens. Fleifel films him sitting despondently, on the eve of his deportation back to the camp (where he is now), and asks him: “What now?” The work ends on that note.

Without apparently pursuing a conscious ideological agenda, organically, out of its own imagery and internal logic, A World Not Ours exposes the bankruptcy of nationalism and the various political forces at work in the Palestinian camps. The filmmakers do not offer an alternative, nor perhaps should they, but the thinking viewer cannot avoid considering that explosive query, “What now?”

This is genuinely serious and intelligent filmmaking.

To be continued