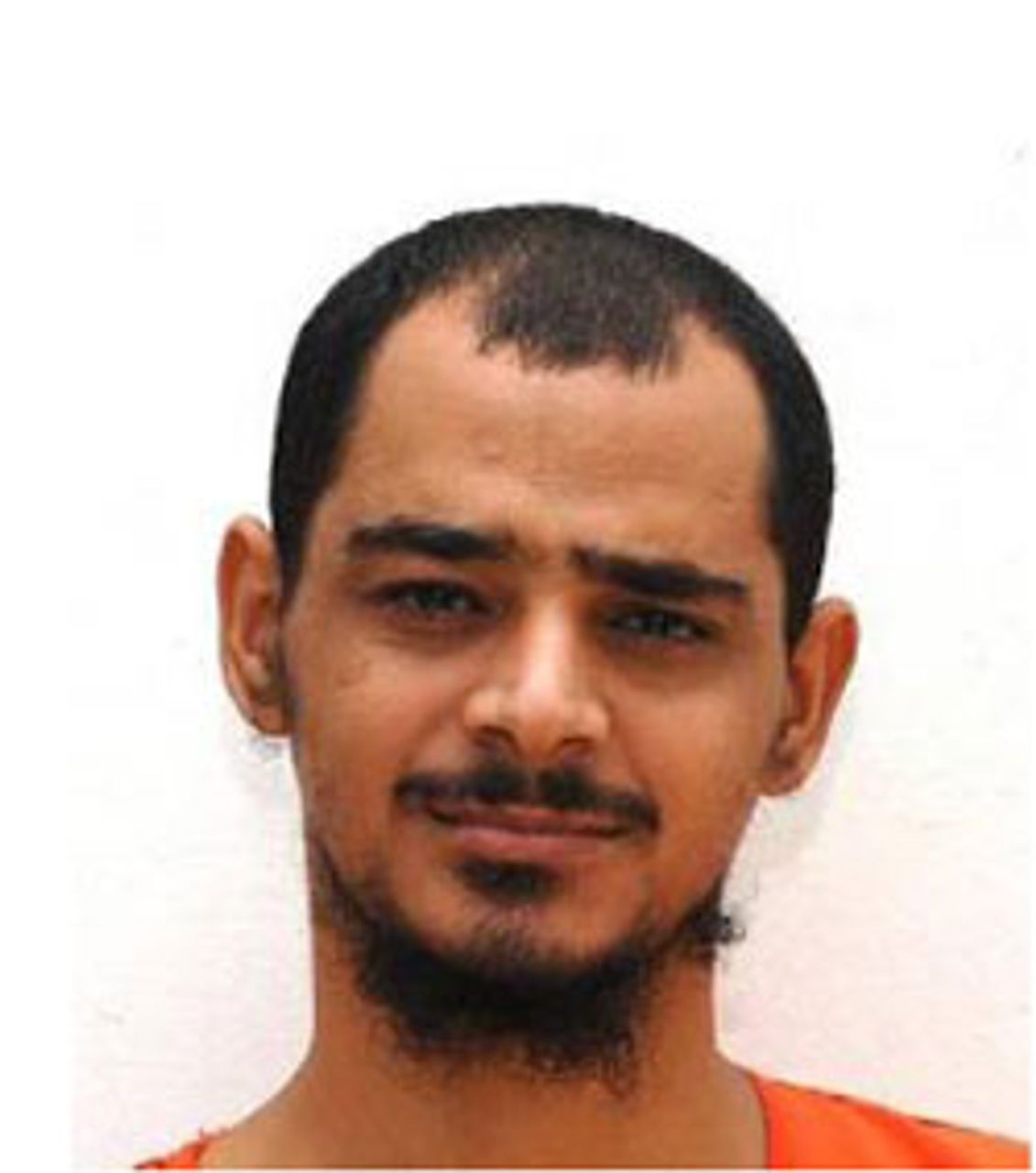

Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif

Adnan Farhan Abdul LatifOn September 10, 2012, Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif died in his cell at the US prison camp at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. As of the day he died, Latif had been imprisoned at Guantanamo for 10 years, 7 months and 25 days. He was 36 years old and left behind a wife and son.

Latif died after enduring a decade of torture and abuse at the hands of the US military and intelligence agencies. His death came after a habeas corpus petition challenging his incommunicado detention was granted by a federal judge and then overturned on appeal, on the grounds of authoritarian legal doctrines promoted by the Bush and Obama administrations.

The failure of the US legal system over the preceding decade to enforce Latif’s most basic rights underscores the collapse of centuries-old democratic legal institutions and the expanding machinery of a police state. Latif’s death constitutes a war crime that, along with the crimes against hundreds of other prisoners at Guantanamo and secret “black sites” around the world, warrants the impeachment, arrest and criminal prosecution of all of the top civilian and military officials in both administrations.

Latif, who was born in Yemen, was swept up in December 2001 in one of the many dragnet-style abductions organized by the US in Pakistan. The US government publicly claimed that Latif was a member of Al Qaeda, but Latif was never charged or convicted of any crime.

Documents obtained and published by WikiLeaks last year revealed that the US government knew all along that Latif was not associated with Al Qaeda. It appears that Latif traveled to Afghanistan not to join Al Qaeda, but to seek medical care related to a 1994 automobile accident that left him with lasting brain injuries. The US government locked up Latif anyway, without any charges or trial, as part of the Bush administration’s newly launched extrajudicial detention and torture program.

The circumstances of Latif’s death are suspicious. The US military initially reported that Latif had been found “unconscious and unresponsive” in his cell. However, in an autopsy report recently delivered to the Yemeni embassy, the US claimed that Latif’s death was a suicide. The US military claims that Latif had accumulated medications in his cell and taken them all at once. This is a dubious scenario in light of the 24-hour surveillance and other draconian restrictions to which Guantanamo prisoners are subjected.

Many questions about Latif’s death remain unanswered. On the one hand, in light of the WikiLeaks revelations and the embarrassment Latif threatened to cause, there was a motive to quietly dispose of him. On the other hand, according to Latif’s attorneys, when the decision in his case was overturned on appeal, Latif despaired of ever getting out of the infamous camp.

The New York Times reported last Wednesday: “Yemeni officials refused to accept Mr. Latif’s remains until they got answers about what had happened to him.”

“Adnan [Latif] was a thorn in their sides,” an attorney representing Latif, David Remes, told the New York Times. “The guards would ask other prisoners how to handle him. He refused to submit. He wouldn’t allow them to set the terms of his imprisonment. He was a constant problem.”

After arriving at the Guantanamo Bay, Cuba facility in January 2002, Latif was repeatedly tortured. He was featured in a 2004 Amnesty International report entitled, “Poems From Guantanamo.” The report documents the horrific torture perpetrated against the inmates, as well as how the prisoners like Latif “turned to writing poetry as a way to preserve their humanity.”

In the report, lawyer Mark Falkoff described his conversations with Latif and Latif’s victimization at the hands of military and intelligence agents: “Upon his arrival in Cuba…he was chained hand and foot while still in the blackout goggles and ear muffs he had been forced to wear for the flight. Soldiers kicked him, hit him, and dislocated his shoulder. Early on, interrogators questioned him with a gun to his head. Latif spent his first weeks at Camp X-Ray in an open-air cage, exposed to the tropical sun, without shade or shelter from the wind that buffeted him with sand and pebbles. His only amenities were a bucket for water and another for urine and feces.”

The report described the conditions faced by inmates like Latif. “During the three years in which they had been held in total isolation, they had been subjected repeatedly to stress positions, sleep deprivation, blaring music, and extremes of heat and cold during endless interrogations. Female interrogators smeared simulated menstrual blood onto the chests of some detainees and sexually taunted them, fully aware of the insult they were meting out to devout Muslims. They were denied basic medical care. They were broken down and psychologically tyrannized, kept in extreme isolation, threatened with rendition, interrogated at gunpoint and told that their families would be harmed if they refused to talk. They were also frequently prevented from engaging in their daily prayers—one of the five pillars of Islam—and forced to witness US soldiers intentionally mishandling the holy Koran.”

The list of the tortures and abuses suffered by Latif would be too long for one article. In one incident, Latif stepped over a line painted on the floor of his cell while receiving food. Amnesty International quotes Latif’s account of the response: “Suddenly the riot police came. No one in the cellblock knew who for. They closed all the windows except mine. A female soldier came in with a big can of pepper spray. Eventually I figured out they were coming for me. She sprayed me. I couldn’t breathe. I fell down. I put a mattress over my head. I thought I was dying. They opened the door. I was lying on the bed but they were kicking and hitting me with the shields. They put my head in the toilet. They put me on a stretcher and carried me away.”

Latif participated in a hunger strike in 2005, which the US military called a “voluntary fast.” (See: Guantánamo Bay hunger strike enters third month). The military responded with a brutal retaliatory force-feeding regime. To break the strike, feeding tubes were regularly forced through the noses and down the throats of inmates with no anesthetic, often with blood and bile still on the tube from the previous victim.

Mark Falkoff wrote in the Amnesty International report, “Twice a day, the guards immobilize Latif’s head, strap his arms and legs to a special restraint chair, and force-feed him a liquid nutrient by inserting a tube up his nose and into his stomach—a clear violation of international standards. The feeding, Latif says, ‘is like having a dagger shoved down your throat.’”

Attorneys representing Latif filed a petition for habeas corpus on his behalf in 2004. The writ of habeas corpus is an ancient legal procedure by which prisoners can challenge their incarceration and the conditions of their confinement before a judge. One of the central purposes of the writ is to prevent incommunicado detention without trial. The writ of habeas corpus is called the “Great Writ” because without the right to get into court in the first place, the rest of a person’s rights are eviscerated.

The Fifth Amendment to the US Constitution, part of the Bill of Rights ratified in 1791, prohibits detention without trial. The Fifth Amendment states: “No person shall be…deprived of…liberty…without due process of law.”

In July 2010, Federal District Court Judge Henry Kennedy granted Latif’s habeas corpus petition and ordered his immediate release on the grounds that the government’s version of events respecting Latif’s alleged participation in terrorist groups was not plausible. In an earlier period, a decision ordering the release of a prisoner who had been held by the government for years without being tried or convicted of any crime would have been immediate and uncontroversial. In the recent period, Judge Henry Kennedy’s decision stands out as exceptional.

Instead of releasing Latif, the Obama administration appealed the district court’s decision, raising authoritarian legal doctrines and asserting unreviewable presidential “wartime” powers. In October 2011, the DC Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Judge Henry Kennedy’s decision.

The DC Circuit’s decision in Latif v. Obama, available here, attributed a presumption of validity to government reports that purported to link Latif with “terrorism,” despite widespread inconsistencies and inaccuracies in the reports. The DC Circuit opinion essentially overturns the presumption of innocence for designated “terrorists,” placing the burden on the accused to refute the presumptively correct position of the government, rather than requiring the government to overcome the presumption of innocence. The DC Circuit noted specifically that “a Guantanamo habeas petitioner is not entitled to the same constitutional safeguards as a criminal defendant.”

Latif petitioned for the Supreme Court to review the DC Circuit’s decision, but the Supreme Court refused to hear the case.

Secret documents published by WikiLeaks in April 2011 establish that the Obama administration—at the time that it appealed the order granting Latif’s habeas corpus petition—had long known that Latif was not a member of any terrorist group. In other words, the Obama administration knowingly petitioned the DC Circuit to apply a presumption of reliability to determinations that were known to be unreliable.

Despite promises to close Guantanamo Bay during his 2008 election campaign, Obama prepares to enter his second term with approximately 167 men still locked away.

A poem by Latif called “Hunger Strike Poem” contains the following lines:

They are artists of torture,

They are artists of pain and fatigue,

They are artists of insults and humiliation.

Where is the world to save us from torture?

Where is the world to save us from the fire and sadness?

Where is the world to save the hunger strikers?