Williamson, West Virginia, is a center for coal transport and the Norfolk Southern railway. The population of the city has fallen to a third of what it was in the 1930s, when residents constituted a mass and militant workforce in the Mingo County coal mines and the rail yards. Today, only some 3,400 people reside in the city, and one in three households subsist on less than $10,000 a year. Among the 44 percent of residents classified as being part of the labor force, official unemployment stands at 12.1 percent.

Massey CEO Don Blankenship’s mansion overlooking Williamson, West Virginia

Massey CEO Don Blankenship’s mansion overlooking Williamson, West VirginiaConditions of mass unemployment and destitution coexist with staggering wealth. Massey Energy’s billionaire CEO Don Blankenship owns a residence on a mountaintop overlooking the town, which residents described as a “castle.” In 2009, Blankenship received pay of $17.8 million and a deferred compensation package worth $27.2 million.

A WSWS reporting team spoke to residents at Goodman Manor, a large subsidized apartment complex downtown about declining conditions and corruption in Williamson.

Ronald Childress worked for 38 years as the head cook at the Williamson hospital. “I started working at the hospital in 1968,” he told WSWS reporters. “At one time, this was a little city.

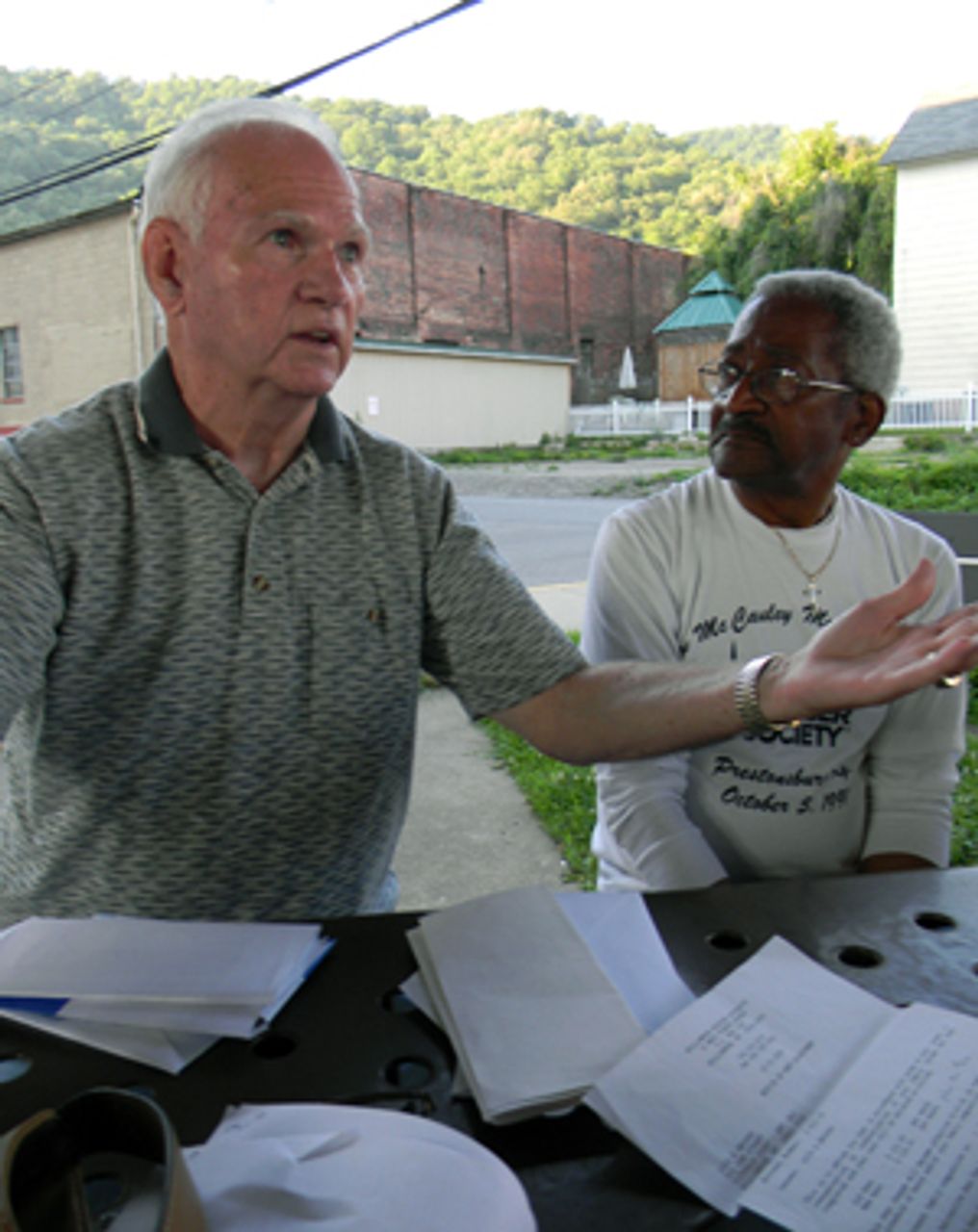

Juanita Barker and Ronald Childress. Behind them stands the gutted Olympic Opera House, where theater troupes from New York and Cincinnati once performed.

Juanita Barker and Ronald Childress. Behind them stands the gutted Olympic Opera House, where theater troupes from New York and Cincinnati once performed.“We had all kinds of shops in town—Murphy’s, Halls Department Store, a JC Penney’s, Cox’s Department store. We had a Sears Roebuck that moved out. We had three or four grocery stores; now to buy groceries you have to go out of state,” he said, indicating toward the bridge across the Tug Fork River to Kentucky. “I wouldn’t dare walk that.”

A section of downtown Williamson. At the top of the hill stands the former hospital.

A section of downtown Williamson. At the top of the hill stands the former hospital.“This has always been a booming town, with coal and the railroad, and we have two hospitals.” Other residents pointed out that the Hubbard Motor Company was just across the street, and noted that the town once had nightclubs, and a tea room. “We had four theaters, and a drive-in theater.”

“After they built the mall on the Kentucky side, all the businesses moved over there,” Ronald said. “There is no theater now. A lot of us do not have transportation—I don’t have a car. You have to call the night before for the bus, which runs twice a week. You can walk for miles down the highway, or you can make an appointment for the one transportation service available and pay $1 each way. You just do the best you can.”

Juanita Barker, gesturing to another resident, told the WSWS, “This old man out here, he’s had a bad car wreck, brother Harry, and he’s real crippled, and he tries to get a ride to his doctor’s appointment. He sits out there on that bench, and waits, and waits, and waits. Can’t go.”

“There’s a lot of old, old money still in this town,” Ronald said, “but it’s sitting there. They’re not putting any of it back into the community. See this building right there,” he said, pointed behind him. “Now, years and years ago that used to be an opera house.”

Juanita explained, “It was an opera house, and people played the piano, and had these curtains that pulled back and people sung on the stage, and put on plays. This was before our time. They shut down the opera house, then put in a drycleaners, a TV repair shop—now it’s just full of junk.”

Strosnider building housed visiting doctors in the 1960s. Residents said the building changed hands a few times. “Old money built this.”

Strosnider building housed visiting doctors in the 1960s. Residents said the building changed hands a few times. “Old money built this.”Juanita said, “I was a seamstress when I was young. I worked all over town sewing, and worked at the men’s shop downtown until I got the sugars [diabetes] to where I couldn’t see well enough to sew. I was 23 years old in 1968, when my husband got killed in a car wreck. I had three young children at that time. There wasn’t much opportunity for a woman except getting married or learning something. I had no education and got married at age 17.

“There were no drugs then,” she added. “Now the city has a huge drug problem and people have nothing.

“Many houses on this side of town have no water or sewage service,” Juanita said. She explained, “The old mines up the hills here were refilled with sludge, and it contaminated the water supply. It ran into people’s wells and came out of their faucets.

“This river, you do not eat the fish! The city government put a notice in the paper about six months ago saying ‘Don’t drink the water until further notice’—it’s not safe. It’s not been tested, not been treated. Don’t take a shower in it. They never lifted the advisory! When people asked about it, the city officials said, ‘Oh, there’s nothing wrong with the water’—but they said, ‘do not brush your teeth in it!’ People do drink the water of course; what choice do they have? A lot of people can’t afford to buy water, and can’t get over to the store…. Massey has destroyed the wells and the water, and they are supposed to fix it.

“There’s no money for us. What money comes into this town, the politicians take it.”

As conditions deteriorate for the working class and the poor in the state, Democratic Governor Joseph Manchin has promoted an initiative to give cities the authority to demolish or order residents to fix at their own expense properties that they classify as dilapidated. Large numbers of housing units in the coalfields region would likely fall into such a category, opening the way for the demolition of entire neighborhoods.

“Old houses aren’t the best in the world,” Juanita commented. “They need work, but poor people can’t fix them. Just last summer, the city took some people’s houses and put them out. They tore down people’s houses up here at Peter Street, and sold the land.”

Residents of subsidized housing were subject to the same types of treatment. Conditions in the apartment complex were appalling. Garbage bins in the hallways were rarely emptied, and residents spoke of flies and maggots all over the walls and floors. Juanita explained, “I came here seven years ago. There’s not been one penny spent inside of this building. It’s supposed to have a roof, a new water system, air and heat. They just put in some old blinds instead, and pocketed the money.”

The building has no central heating and cooling system in use, which is a violation of the federal Housing and Urban Development (HUD) standards for subsidized living arrangements for the elderly and disabled. Residents said the building manager ordered them, under threat of eviction, to remove air conditioning units installed in their windows in the days before inspections. In this way, the manager hoped, no one would suspect the apartments lacked a central air conditioning system.

Residents said in the building they had “church meetings three to four nights a week, and Bingo from 4 to 8 p.m.” Residents spoke of being threatened with eviction for complaining about private businesses that were illegally using the lower floor of the building, including reserved parking.

Several residents remarked bitterly on the presence of religious organizations and prayer services in the public housing. For the 100 apartments, four computers had been available for residents eager to access the Internet, but these were taken away and converted into monitors for new security cameras.

Ernie Brooks

Ernie BrooksErnie Brooks, a former coal miner, added, “The mayor, the governor, the legislators, they don’t have an interest in this town. They don’t put money in it, and it’s falling down. The Williamson Daily News doesn’t talk about anything in our lives. They only echo what the politicians and the coal companies want them to say.” Holding up a copy of the paper, residents pointed out a banner at the top. “Now what does it say?” Ronald asked. “‘In the heart of the trillion dollar coalfields.’ It used to be the billion dollar coalfields, but it’s the trillion dollar coalfields now.

“In a town like this, why do you have banks like this?” Ronald gestured down the hill toward the multiple story bank facades, including the First National Bank where the Mingo Theater used to be. “Coal and drugs,” he said. “The cops have been involved in millions of dollars in drug trade; federal agents recently raided the warehouses over the tracks from here, and yet nobody has gone to jail or has even been fined.

“The drug problem is atrocious. But then they have no real rehabilitative services for the people who get hooked. The town has one outpatient methadone clinic, and no counseling services.”

The former Sycamore Coal Company plant

The former Sycamore Coal Company plantResidents expressed concern over the location of the new consolidated high school, atop a “reclaimed” mountaintop removal site. The buses will go 25 miles over three mountains to bring kids to the school. “It’s going to be ‘state-of-the-art,’ but nobody can get to it,” Juanita said. “And every time you put something on it, it falls down in the mines under it. They’re still settling. It's not going to be safe.” Ronald compared the school construction to the Big Sandy prison built on a reclaimed mine site near Inez, Kentucky. “Everything at that penitentiary kept falling in. The walls are cracking and everything. And that school’s going to be the same way. It’s going to endanger the kids up there. I think it’s just a waste of money.”

“They don’t care about people,” Ernie said. “All they care about is money. You look around, and you see trees growing up inside of houses. And there are people still here, living in them! There are a lot of things that are even worse than what I’m telling you.”

Williamson high school is slated for closure

Williamson high school is slated for closureErnie described his experience working at US Steel, which operated one of the largest coal mining sites in the world in the latter half of the 20th Century in the town of Gary, West Virginia. The operation employed thousands, and the struggles of the miners had produced a higher standard of living and commerce for the entire region. In 1986, it shut down, shattering the local economy.

Ernie explained the various jobs he did underground. “When you go in the mines, you’re a red hat. That means you can’t be at the face of the coal. So at first I went behind the continuous mining machines, picking up the coal. Then I was put to work with a crew pulling pillars, and I had to put up timber to keep it from collapsing. Next, I was put to working alone at pulling the pillars, with no help. It was dangerous work.

“One day, all the lights were out—you’ve never seen darkness until you’ve been in the mines. That day I made the decision that if I made it out of the mine, I was never going back down. I got a job hauling gas—but it paid less than half of what it paid to be in the mines.

“I was in a miners’ strike in the early 1980s. Really, the strike was just set up. It was never going to be settled for us to get our jobs back. When I worked there, it was UMWA (United Mine Workers of America)—but they broke the union. They gave us buyouts. I believe that the union was against us, and the company was against us.”

Referring to Richard Trumka, UMWA president during the period and now the head of the AFL-CIO, Ernie said, “I didn’t trust him any further than I could throw him. We didn’t get a contract—Trumka didn’t do us right. He kept talking about getting a contract, getting a contract, and he got a contract all right, but it wasn’t a good contract, it was a company contract. That means that whatever they say they want you to do, you do.”

Referring to the April 5 explosion at the Upper Big Branch mine, Ernie added, “Just like when the 29 miners got killed: whenever an inspector comes in and says something isn’t safe, and then when he goes away, the miners are going to have to go right back in there—or they’re told to go home and don’t come back.

“Don Blankenship is the person to break workers. They looked and looked for someone like that, and they found what they were looking for in him. He doesn’t care—he’s ruthless, with an animal mentality. That’s the way he is. I wouldn’t work for Don Blankenship. The way he runs things, he kills people.”

The social crisis in Appalachia: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

Interviews and related material: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5